How Colleges Make More Money Than God By Giving It Away

Some people naively dismiss the insane increases in the Cost of Education over the last 50 years as merely Vanilla flavored Cost Disease. Don’t be fooled by the marshmallow swirl — this is Rocky Road, and the shit chocolatey-covered almond pieces are buried deep.

A very brief summary of what’s to come in this essay:

College degrees are more valuable than ever in post-industrial economies, so applicants to top-tier schools are up 240% over the last 25 years

Meanwhile, available spots at top-tier colleges in America have increased just 2% over the last 25 years

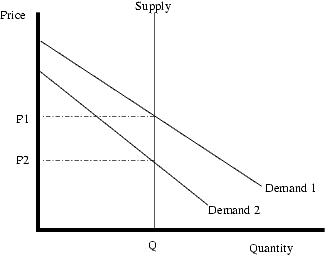

Microeconomics 101: Fixed Supply + Increased Demand = Increased Price

That’s the obvious part

The non-obvious part is that this is intentional

Because the Charity-status ( 501(c)(3) ) of Colleges in America depends on more-than-half of their students being unable to afford the education (read: “receiving financial aid”)

Not in any legal code and statute you can find — but because the Ivy League was sued by the Department of Justice for price-fixing and beat the case by arguing that since more than half their students received “financial aid” — a lot of it — this was a charitable gift policy, not a pricing policy, thus tying together the charity-status of College and the percent of students receiving “financial aid” in a court of law…

…and Common Law puts tremendous weight on those court decisions, to say nothing of the political pressure that could rapidly be brought to bear on Institutions with endowments bigger than the budgets of 150 countries and most of the Fortune 500’s cash balances, yet which pay no taxes on their investments and charge middle-class Americans double-digit percentages of family Wealth for a degree whose cost is not tax deductible for the family paying $50,000+/year in tuition

All this is excused if people believe the true cost is even greater still, and merely attending college necessitates an act of immense generosity and charity on the part of that college…

That Charity-status protects the Investment Returns of College Endowments from Uncle Sam & the IRS

Investment Returns Compound over time, and there is no more powerful force on Earth — anyone not playing the game to maximize Compound-returns will lose to everyone who is

Investment Returns already generate more revenue than undergrad tuition income at: Princeton (911% more), Harvard (529% more), Yale (254% more), MIT (118% more), Stanford (115% more), Brown (29% more), Duke (13% more), Dartmouth (9% more), and U Chicago (6% more)

Undergrad tuition brings in just 10% - 20% of total revenue at the Ivy League / Top-10 schools not listed above. Undergrad Tuition is not more than a quarter of revenue at any of these schools.

Thus: if Colleges want to keep their Investment Returns tax-free, Tuition MUST remain unaffordable for at least 50% of undergrads

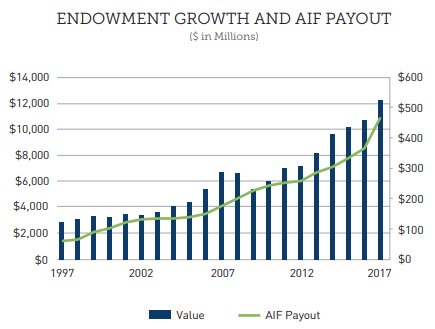

You think its your TUITION dollars that add $1 billion a year to this?

Ricardo’s Cost Disease

The traditional formulation of Baumol’s cost disease is quite simple: the cost of [SOMETHING] is not related to the direct cost of providing that [SOMETHING], but to the cost of the [MOST PRODUCTIVE OTHER THING] that could have been provided with the same resources instead.

They say there is nothing new under the sun, so naturally Baumol’s cost disease is a restatement for the modern era of a Law of economics developed by a Founding Father of the dismal science: David Ricardo.

The Law of Rent states that the rent of a land site is equal to the economic advantage obtained by using the site in its most productive use…

And Adam Smith himself wrote in The Wealth of Nations:

The rent of land, therefore, considered as the price paid for the use of the land, is naturally a monopoly price. It is not at all proportioned to what the landlord may have laid out upon the improvement of the land, or to what he can afford to take; but to what the farmer can afford to give.

In a Feudal Agrarian society, land is the major productive asset. So of course this conversation between Adam Smith and David Ricardo would be about Rent — what else would the average man spend his Wealth on?

But in 2018, we’ve got so many potential outlets for Capital — capital C — that Ricardo’s Law of Rent bleeds into every possible cost, from Infrastructure to Education to the Barbershop.

However.

Lay of the Land: Education is a More Complex Flavor of Cost Disease

Conventional wisdom says “a generation” is about 25 years, plus or minus 5.

3 months ago, the class of 2022 began their first semester at my alma mater: MIT.

A Generation ago, the class of 1997 also began their first semester.

How has this small world of education changed in one Generation?

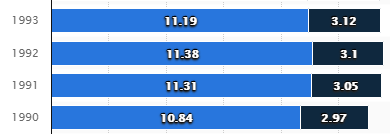

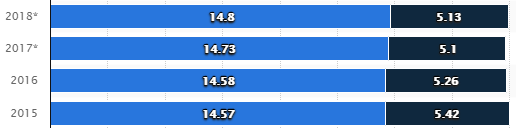

Total US College Enrollment Up 39% from 1993 to 2018 (units below are millions of students):

How many people actually applied each year? Unclear. We genuinely don’t seem to have that data — or at least Google didn’t dig it up for me yet.

Similarly, you can cut the green line off on my previous essay’s chart around 1993…

…and see that the cost of this education has increased about 300% since 1993 (1,225% / 300% - 1)

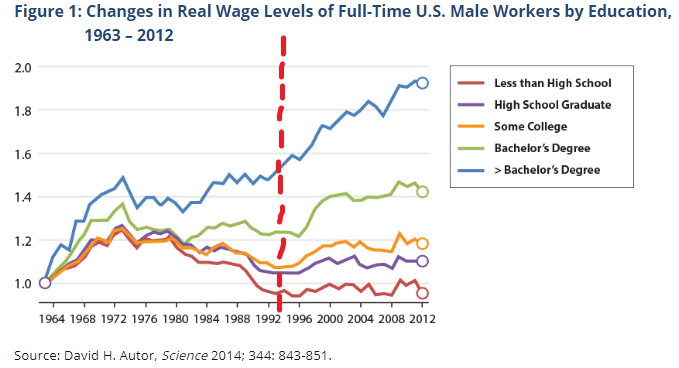

And to re-include just one more chart, you can see that 1993 marks a period that began a ~20% increase in real wages for male workers with Bachelor’s Degrees

So over this last Generation, a Bachelor’s Degree or higher has increased real wages by 20% - 40%, the total number of college-enrolled students has increased 39%, and the cost has increased by ~300%.

Adam Smith suggests that the cost of this education should rise according to what the middle-class can afford to give.

I concur.

David Ricardo suggests that the cost of this education should mirror the maximum possible benefit from the education, regardless of what major was chosen and GPA achieved.

I concur.

Baumol’s Cost Disease suggests that the cost of this education should rise with the productivity of the rest of our economy.

I concur. And incidentally, the Cost of Tuition chart above is not-inflation-adjusted, so if we look at nominal-GDP between 1993 and 2018 we find it increased from $7,247B to $20,412B — or 182%. That is to say, perhaps as much as 2/3rds of the increase in the cost of education might be driven by an increase in overall productivity over the same time period — assuming that education is well-positioned to capture a large share of that surplus production.

Which it is.

But what of the remainder?

Mens et Manus and No More Bodies

I’m going to focus on MIT because I love the school and I was lucky enough to get in 10 years ago today. I focus here because I know it best, and I know it is the best. Which brings me to MIT’s Class of 1997, who began their undergraduate journey 25 years ago. Being the advanced institute that it is, MIT kindly uploaded the admittance stats for this class:

http://news.mit.edu/1993/class-0331

Yes, you read that right.

32% of applicants were accepted to MIT last Generation.

Total class size: 1,100.

Step forward a Generation, and look at today’s MIT Class of 2022:

Of those 1,464 admits, 1,122 of them ultimately decided to make MIT their home for the next 4 years (good choice!).

Thus, the Total Applicant Pool increased 239% over this 25 year period — from 6,410 to 21,706.

Meanwhile, Class Size increased 2% over that same time period, from 1,100 to 1,122 — just 22 extra bodies.

The Cost of Tuition increased 171% — excluding room & board and other expenses — from $19,000 to $51,520.

Education therefore exists at the intersection of increased productivity driving up overall costs — Vanilla Cost Disease — with massively increased competition in an ever-growing applicant pool for a fixed number of spots. My claim is that this is a feature, not a bug.

Due to the way signaling, ranking, social hierarchies, and prestige work in human society, opening a brand new University does not lower the value of MIT & the Ivy League schools. It actually increases their value. Not attending has the same signaling weight as attending, just in the other direction.

In a world where 32% of applicants are accepted to MIT, perhaps the signaling value is moderately strong. In a world where 93.3% of applicants are rejected, the signaling value of being one of the lucky few goes up, not down. People tend to like people that other people like (lol) — but they tend to avoid people that other people have rejected. The impulse to avoid is stronger than the impulse to seek-out, because the downsides of social-association can be unbounded.

Why is increasing competition for a constant number of spots a feature (intended), not a bug (accidental)?

Question: As someone who has already applied, been accepted, attended, and graduated from a prestigious Institute, is my personal value-by-association-with-MIT increased or decreased by MIT becoming more selective?

Trivially: my value increases as the value of an MIT-stamp-of-approval increases.

Spoiler alert: this describes all alumni, staff, and current and future students.

So how do you increase the prestige price value of a social signal?

Thanks to McGill for this chart — here’s a link to MIT’s Microeconomics class if anyone needs to brush up on the fundamentals. Don’t worry, taking this class online for free doesn’t lower the value of getting accepted by MIT — why is that? 6.7% btw

This is where I add that my own Class — 2013 — only had to deal with a 10% Admit Rate at MIT, a “record low” at the time. But 25 years from now, when the admit rate is 2%, I’ll be very appreciative of the increased prestige that comes by association with such an elite institution.

Again — I’m only focusing in on MIT because I love the school and I was lucky enough to get in 10 years ago today. Don’t think Yale didn’t accept 20% of applicants in 1995, UChicago didn’t accept 77% of applicants in 1993, or that the Harvard Class of 1988 didn’t admit more kids than the Class of 2022 just did. Because all those things are true.

I leave as an exercise for the reader to explore how massively increased competition for strictly limited spots at the nations most prestigious institutions impacts cultural cohesion and the perception of the elite in the rest of the country — especially during a time in which the stamp-of-approval from said prestigious institutions becomes ever-more critical to career success and wage growth.

Pictured: College admissions for the Class of 2035

One More Thing: If you're not paying for the product, you are the product

There’s an extra layer to this strange ice cream cake of constant-supply education, I told you the almonds were buried deep: we didn’t get to Tuition yet.

If you actually followed that earlier “$19,000” link to a 1993 MIT article on their Tuition, and you read the President’s quote at the end, and you were wondering what he meant by:

These two actions are consistent with our stand against the Justice Department's anti-trust suit, and are major driving forces in the development of an imbalance in our operating budget.

You’ll be pleased to read that MIT prevailed in defending its practices from the Justice Department in December, 1993:

The case involved the widespread practice of pooling information about applicants for financial aid. The nation's brightest high school seniors often apply to several elite colleges. To prevent a bidding war, with colleges "buying" the best students with big aid packages, some institutions share information about their applicants, agreeing to limit their offers to the students' financial need.

I was under the impression that service-providers entering a “bidding war” to offer consumers lower prices was known as “Competition” in America. Thanks Uber & Lyft, btw. And I thought the opposite — NYTimes dubbed “cooperative practices” in that article — was known as “Price Fixing”?

And since when was the salesman of a service the right person to determine my financial “need”?

A Charitable Misunderstanding

In true Ivy League fashion, the eight Ivy League schools targeted by the Justice Department agreed to sign a “consent decree” barring such price fixing cooperation, while admitting no wrongdoing at all. Shoutout to the financial crisis of 2008 (ctrl-f for “wrongdoing” in that bad boy if you hate low blood pressure).

In true wronged-nerd fashion, MIT soldiered on and fought the Justice Department, once more teaching the world that if you start an argument with a nerd it will only end when somebody starts crying.

Pictured: Justice Dept., circa 1993

What’s great about this is that MIT marshaled the media (see: NYTimes above) and published their own view of the case while it was being litigated. Which means we can read their argument as they present it best:

In presenting its case, MIT made these key points:

i) MIT financial aid is a gift policy, not a pricing policy.

ii) Tuition covers only half the cost of a student's education; all students receive a subsidy of more than $16,000 from MIT's endowment and income.

iii) Fifty-seven percent of students receive aid at MIT.

iv) The consent decree gave unequal treatment to non-athlete students by specifically excluding Ivy League athletes from the general ban on collaborative agreements.

Ignore that last point about athletes as it’s not important to MIT (shocking: Ivy League schools still wanted to be able to price fix cooperate in attracting star athletes), and focus on the first three points.

At first glance, this passes the sniff-test. MIT claims to be operating a charity — literally, that’s what they claim: “MIT said its need-based policy of distributing MIT scholarships is a policy of charitable gifts to students…” They say they can barely keep the lights on if they receive $51,520 in Tuition from students, they say they give all students a permanent 50% discount out of benevolence, and then they actually have to reach into their coffers and hand-out even more money to the 57% of students who otherwise would be unable to attend.

Interesting note: the percentage of students who receive “financial aid” has not changed in the last 25 years. How perfect is that? The cost of MIT has gone up $32,520, but the number of kids in “financial need” has stayed the same! Pretty awesome that the 42% of families who don’t get any aid at all have all got at least $130,000 (4-years of tuition) in extra Wealth!

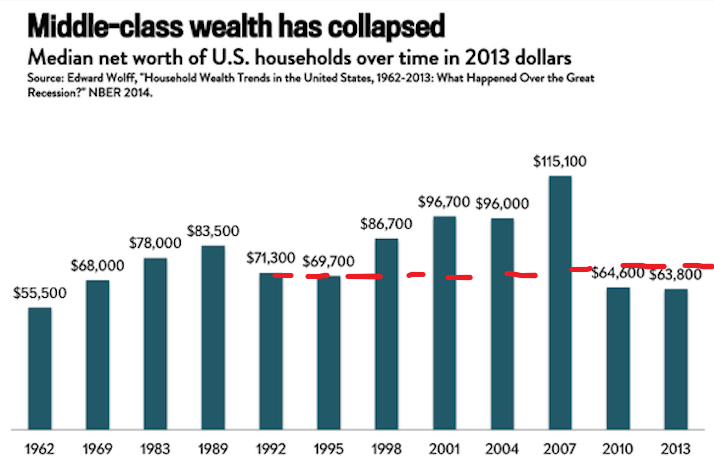

I said I wouldn’t include another chart from my first essay, but sometimes you just gotta do it. Call me a hammer, if you must.

Hmmmmmmm.

Back to the “charitable gifts to students”: Follow the actual trail of REAL dollars, and not the imaginary zeroes and monopoly money shifted around behind the scenes — when MIT gives you $40,000 of financial aid, they don’t take a full tuition from another student and give it to you, they don’t reach into a vault and give you physical dollars. They simply charge you less, a mere “discount” — the exchange is theoretical, monopoly money.

When you drop out after your first week to start the next Facebook…you don’t owe MIT $40,000!

The tax implications of this — you can’t fuck the IRS — are zero.

More Economics: Variable vs. Fixed Costs and a Slush Fund

You think of Tuition in terms of individual student amounts because that’s how you experience Tuition and that’s exactly how The Institute presents the bill to you. “This is what it costs us to educate you, individually! Yes, all $51,520 of it! Times two!” But the actual marginal cost of educating a given student at MIT is approximately zero (spoiler alert: you will not get much tender affection from your lecturers at MIT, and after the first week of class there’ll be many empty seats in your lecture hall).

Universities are DOMINATED by fixed costs, not variable costs. Lab operating costs, building construction, rents, research salaries, professor salaries, administration salaries, energy costs, etc. etc..

Which means the cost of operating The Institute for a given year is determined before any kids are admitted.

And this cost is funded by three things: The Endowment and Income.

“But that’s only two things!”

Right, that’s the magic. Read MIT’s second key point again. The Tuition you’re asked to pay ($51,520!!!) “only covers half of The Institute's costs” (yes, they still say the same thing today that they said 25 years ago, brush up on Common Law to understand why their language has been identical for 25 years), so the remaining fixed cost must be covered by The Endowment and “Income”. What’s included in “Income”? Tuitions from other students, of course!

Little pink slice in the bottom right

Duh, how else could a college get money? “Net of discount” just means “ignore all the fuzzy monopoly money and just look at what we actually got wired by the entire student body.”

Your Tuition doesn’t pay for your education — it goes into a shared pot that pays for the fixed costs of educating the whole student body, including you.

To the extent that Tuitions received don’t cover all the costs, gifts from Benevolent Alumni / DARPA and Investment returns from the Endowment’s portfolio must necessarily fund the remaining balance.

Two Plus Two is Four, Minus One that's Three: Quick Maths Dodge the IRS

Flash back to the comment that has been clearly stated on all MIT admissions pages for the last 25 years (to remind the Justice Department that this is a Charitable institution):

The actual cost of an MIT education is about twice the annual tuition…

And then look again at the pie-chart of Revenues above. If Tuitions received total $361.5M and that amounts to half the “actual cost” of an MIT education, then the full cost of educating undergraduates could be $723M.

But that must be understating the number hugely! MIT claims that the full cost is about double the list price of $51,520, or about $100,000, and since “58% of our undergraduates receive MIT Scholarships that average $45,542 per student” the Tuition Net of Discounts income of $361.5M must be much less than the actual amount MIT needs, because most of the kids get “financial aid”.

Thankfully, we can do napkin math. Since there are approx. 4,500 undergraduates at The Institute, MIT’s own words suggest that the actual Fixed Cost of providing MIT educations to all those kids must be $100,000 * 4,500 or…$450M.

Huh??? $450M is pretty close to the total income from Tuition in that pie-chart. How can MIT be subsidizing half the costs for every student, then giving 58% of them another huge discount in “financial aid” that averages $45,542, and yet still be collecting such a huge fraction of the needed amount??

This is like those goddamn word-problems they put on the Math section of the SAT…screw that. Have a spreadsheet instead:

Uncharitable observation: if all students paid exactly the same price — zero financial aid — and MIT collected the same $113M in total tuitions, the revenue from a new student would be $25,105 per student per year. Rephrased: the Expected Value of a marginal student to MIT is $25,105…

Answer: apparently they don’t — this doesn’t add up to the $361.5M in income listed as coming from Tuitions. Not even close.

The 1,890 students who pay the full sticker price of $51,520 a year contribute about $100M to MIT’s income statement. The 2,610 students who receive some form of aid, contribute another $16M. That’s $245M short of what MIT actually collected in Tuition in 2016.

Even if every undergraduate paid $51,520 a year, MIT would be $132M short. Graduate students, I suppose, must make up the difference? Are the MBA kids really subsidizing undergraduate educations? But then wouldn’t those Graduate students have a cost associated with their own education? Who is actually paying all this tuition?!

And, more importantly, who is subsidizing all those costs. MIT “needs” $450M to educate the undergraduates alone — according to MIT — and those guys are only contributing $113M…

Whatever the shortfall really is, it’s got to come out of the mythical Endowment, right? That’s what this is all about. That’s why this is a subsidy, “aid”, a charity.

The Case for Charity: A Charity Case

Is this Charity?

If tuition had not increased by $32,520 over the last 25 years, what percent of undergraduates would qualify for “financial aid”, by the standards of 2018? If 58% of undergrads qualify for “aid” when the price is $51,520, surely many fewer would qualify for aid if tuition were a mere $19,000 a year.

Would under 50% qualify for “aid”? Almost certainly.

Under 25%? Perhaps.

At that point, if only a minority of students are even receiving any aid at all — IS THIS STILL A CHARITY?

Units are in millions btw

You know they don’t pay taxes on that, right?

You know that means it will compound faster than any other source of Wealth in the country, right?

Or do you still not understand compound growth?

The Justice Department lost their suit against MIT on the merits of MIT’s argument that they operated a Charity, as evidenced by the number of students receiving “aid” and the degree of that “aid”, which means there’s legal precedent that you count as a Charity and are subject to different laws as long as more than half your customers can’t afford your education product…

…and you think it’s a coincidence that exactly 58% of students qualify for “financial aid” every year for 25 years in a row?

It’s not “aid” when the price is calibrated to maintain unaffordability and necessitate 501(c)(3) Status.

The eagles of Justice have sharp eyes and sharper talons — best play it safe.

You Can’t Spell Irony Without The Alphabet Soup

There’s a delicious irony here, which is that donations to a college’s Endowment are tax-deductible up to 50% of your Income. This is because that endowment is hypothetically spent “Charitably” funding the education of students that otherwise just could not happen.

They’ve got a point, by the way. Imagine what would happen if a clerical error deleted MIT’s endowment. No other source of Revenue even approaches the magnitude of the Investment gains from the Endowment (well, except the DARPA funding but that’s perhaps unique to MIT) — go back and check the pie-chart if you don’t believe me. If MIT’s endowment evaporated, it just wouldn’t be able to compete for talented professors or afford the latest research labs and facilities — because the cost of those scarce commodities is bid up by all the other colleges who’ve got their own big swinging 501(c)(3)-protected endowments to throw around.

The best way to compete for talented professors and the best facilities is to have the largest pile of money, and then earn tax-free investment returns on that money. I’m not knocking it, everyone else in America learned this at birth, in fact I think it’s in the Pledge of Allegiance — the best way to compete in Capitalism is to have the largest pile of Capital.

So donations to MIT must continue to be “tax advantaged”, and they’ll help you work out how to lower your tax bill by doing so with three different web pages.

Your own child’s Tuition, however — which as we see in the pie chart above ends up in the same shared pile as the donations — is only tax deductible up to $4,000 dollars. Unless you and your spouse jointly make more than $160,000 (i.e. unless you and your spouse both work and have degrees from a school in MIT’s tier), in which case you’ll spend $51,520 on tuition and say fucking thank you.

A Ditty for Your Pity:

Tuition for thee

501(c)(3)

For me

If you get college with no fee

You’re the reason investment returns are tax free

The product is you.

Thank the Revenue Act of 1954 for establishing a legal way to fuck the IRS btw — I said earlier: you can’t fuck the IRS. The emphasis was on you.

The Eight Levels of Giving Tzedakah

Making a donation to MIT appears to satisfy the second-highest level of giving possible, according to a 12th century Jewish sage:

2. Giving assistance in such a way that the giver and recipient are unknown to each other. Communal funds, administered by responsible people are also in this category.

There doesn’t seem to be a qualifier in his ancient text for giving in a way that offers the “greatest tax advantage” or “giving” money that you were never going to see anyway because Uncle Sam had it earmarked in his name — but hey, we make allowances in the modern day.

Since MIT is the one with the 501(c)(3) Charity Status, I wonder where its giving from the mythical Endowment ranks on the ancient scale?

It turns out that lately, colleges like to boast about the size of their endowment — look, I get it — which means we know roughly how big MIT’s is. In the past, however, they weren’t nearly as forthcoming with data about its size. I don’t think you need an advanced degree in Phallocentrism to understand why.

Thankfully, we can hold a magnifying glass to the past with the power of the internet and vague statements made to college newspapers…

In 1990, MIT’s operating budget was $1B dollars, and its Endowment was approximately the same amount: $1 billion.

In 2018, MIT’s operating budget was ~$3.5B dollars, and its Endowment was $16.4 billion

If this is a Charity, they have become remarkably inefficient with their assets over the last generation.

At the bottom of the giving scale we have:

8. When donations are given grudgingly.

7. When one gives less than he should, but does so cheerfully.

Perhaps some received their “financial aid” cheerfully, but my interactions with MIT’s Financial Services arm were like pulling teeth — bloody, painful, leaving a wreck behind and a bad taste in the mouth, and best done under the influence of drugs. To be clear here lest this leaves too bitter a taste in the mouth of readers: from the individual family’s perspective, “aid” is not judged by the magnitude of the “discount” received, but by the percentage of the family’s existing assets the school decides we "need” going forward. While The Institute finds your family “not in need” of an extra $20,000 this year, you’ll find their Endowment increased by another billion dollars…

How much should MIT give though? Only God knows. Somehow they’ve been able to give, and give, and give, each and every year to students, subsidizing them all for 50%, and then giving 58% of them another 80%+ discount…and yet the Endowment has grown by $15.4 billion.

If this is a “charity”, I’d hate to see what they think a business looks like.

Big Business is Booming

A Generation ago, The Institute was able to fund its Fixed Costs with Tuitions, donations, grants, and an Endowment equal in size to its operating budget.

Today, it needs Tuitions, donations, grants, and an Endowment 4.7x the size of the annual budget.

An Endowment that has grown 1,500% in 25 years.

While the class size has grown a mere 2% — don’t forget the first half of this essay.

A JPMorgan colleague once said to me: the power of compound growth means the best way to give to charity is to invest wisely today.

Self-serving, of course, but all the best rationalizations are. But it turns out he had it the wrong way round: perhaps the best way to make money is actually to give money.

Not so much of it that you can’t compound what you’ve got, though: just enough to stay 501(c)(3).

Which means your product must remain unaffordable, to justify your benevolence.

Which means its cost must grow faster than the wealth of your customers.

The Justice Department’s eagles are out hunting mice, so you can’t conspire too openly to raise prices.

But limiting supply? Despite the Expected Value of an additional student being $25,000-per-year? That’s playing the game on easy mode, and comes with extra bonuses to institutional prestige to boot.

Tuition is meaningless income to MIT now — a drop in the bucket, just 3.2% of their income comes from undergraduate tuition — but so long as the Tuitions are unaffordable for 58% of undergraduates, the Investment returns on $16.4 billion dollars are tax free.

BONUS: this all serves to keep Alumni exceedingly happy with the ever-appreciating value of their degree, ensuring that everyone affiliated with The Institute is happy, donates more (did you even notice Charitable contributions were already a larger source of income than undergrad tuition?), and acts as good brand ambassadors.

EXTRA BONUS: the only people unhappy with this state of affairs are the ones who did not get into MIT, but might have if the admit-rate wasn’t 6.7%, so we can write them off as salty haters and nobody listens to their whining. Of course the plebs would want more places at MIT — but what do they think we’re going to do? Lower standards???

EXTRA EXTRA BONUS: Imagine for a moment the reaction in the admissions office at MIT and the rest of the Ivy League on reading the headline: HARVARD DOUBLES ENROLLMENT

Yield manage that one, rest of the fucking world. The fact that this doesn’t — and won’t — happen tells you much about the “competitive” state of the industry. You learn in the first week of Microeconomics that under a state of Perfect Competition, excess profits are competed away. Harvard got flack this year because their Investment Profits Endowment only grew 10%, to $40 billion dollars. It took Apple 3 years after the release of the iPhone to build up a cash balance the size of the one Harvard now has. Call it Imperfect Competition? Far-From-Perfect Competition? Perhaps Big Business will do after all.

EXTRA EXTRA EXTRA BONUS: Colleges who do not have $10+ Billion dollar endowments (most of them) still have to compete with the Ivy League-tier schools for Professors, Facilities, and more — they just don’t have the investment returns to help pay for it. What’s the only source of income they have left? Tuition.

So both the Big Dogs and the Small Dogs in the yard have an incentive to keep Tuitions unaffordable — the little guys are still relying on capturing all the surplus Wealth from America to keep the doors open (again, see: my first essay). If I were a Small Dog, though, I’d be very worried about the future.

You can’t compete with Compound Growth when you’re only collecting linear returns.

CRITICISM: “There is no statute in the body of tax law that specifies you must be offering aid to 50%+ of your students in order to qualify as a Charity, so a core point of this essay is in fact incorrect."

I’ve edited in an extra sub-bullet in my intro bullets clarifying the structure of my argument a bit. But while this criticism is definitely factually true, it perhaps suggests a different view of our legal framework in America (and its fluidity) from the view I have, where the letter of the law and the Tax-Sheltered status of these orgs is somewhat mutable and has already been subject to prior challenge by the DoJ. By bringing up the prior challenges by the DoJ — which was a case the DoJ lost based on Charity-arguments put forth by MIT — I hoped to highlight that the current status of the Institute as a “provider of Charity” was court-sanctioned based on those exact arguments.

I.e. Because MIT responded to the lawsuit by pointing to the number of students receiving “aid” and the degree of that “aid”, and because they won the case on those merits, Common Law precedent is created that bounds them and suggests that the case could perhaps be re-litigated were that “aid” no longer needed. Certainly the worry must exist.

I suggest this might be driving the magical 58% of students who receive “aid” every single year.

Those who have been lucky enough to be around strategic decision making at meaningful economic institutions in the U.S. will be aware that, contrary to movie portrayals, the average executive is very conscious of the spirit of the law, of both established legal boundaries today and fuzzy social boundaries that have the potential to enact legal consequences in the future. In America, all you need is standing and a sympathetic jury to destroy an institution.

Instead of responding further to this critique in my own words, I hope it's okay to link to two other comments who I think addressed the issue in a better way that I did.

Link: https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=18793049

Link: https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=18794785

Since the discussion has moved on from the front-page of social media, I wanted to include these links for people who might end up here in the future without editing the post itself.

NOTES

I said it twice already, but I’ll say it again to be sure: I love MIT, and feel both intense pride and gratitude about being able to attend (an odd mix of emotions). It’s the only college I ever applied to — I knew I wanted to go before I got there, and I’m much better off having gone than not. If you get in, you should go. This is not an indictment of MIT — it’s an explanation of a “Why?” that I think is somewhat hidden and not widely understood. The reality of publicly writing something critical about a major institution in today’s social climate is that you have to choose your target carefully — as your critique will be read contextually based on the author’s apparent identity. I happen to think that MIT’s actions and philosophies regarding tuition have been among the most admirable of all elite American academic institutions…but as a graduate of MIT and not Harvard, I only have so much standing if I want my criticism to land fairly. And the bitterness expressed above re: interactions with MIT’s financial aid department provided plenty of genuine feeling for the rest of this essay.

I worked in the call center soliciting donations from Alumni as an undergrad — the people were great, the job was fantastic, the pay was excellent, the hours were flexible, the Alumni were wonderful and happy to speak to me, and it was just a good experience all round. If you need a job in college, I recommend it. Bonus for MIT kids today: you might get to see me on your training video!

When MIT mandated freshmen live on campus, there was actually a decrease in admitted Class size. Much credit to Dean of Admissions Stu Schmill for increasing the class size back to prior levels

Credit to Philip Greenspun for articulating some of this a whole generation ago. There truly is nothing new under the sun: https://philip.greenspun.com/school/tuition-free-mit.html

Credit also to Tyler Cowen and others in the rationalist sphere who write online and first introduced me to the question: “why don’t universities add more spaces for undergrads?”

- Overview

- Ricardo's Cost Disease

- Education is a More Complex Flavor of Cost Disease

- If you're not paying for the product, you are the product

- A Charitable Misunderstanding

- Variable vs. Fixed Costs & A Slush Fund

- Quick Maths Dodge the IRS

- The Case For Charity: A Charity Case

- Spell Irony

- Eight Levels of Giving Tzedakah

- Big Business is Booming

- Notes