How great nations are built on the backs of great companies — and what you can do about it

Note: don’t start reading this one on your lunch break unless you can read 150+ words-a-minute. I’m torpedo-ing my shareability here by not breaking this up into bite-size sections to help the great algorithms.

This essay is the outcome of a simple observation: you cannot build a massively successful nation without building at least one massively successful company. The well-being of Great Nations is tightly linked to the well-being of their greatest companies.

The thread of this essay then follows that observation from successful Tech strategies through to Apple, China’s Big Banks, Japanese wartime industry, and Saudi Oil, then on to thinking holistically about an economy, pains of German reunification, and all the way through to the role of Interest Rates, Blitzscaling, and the Federal Reserve in today’s economy.

As we’ll see below, much of the dominance of today’s American economy is thanks to its successful Tech industry. The internet age means that the Twitter feeds, personal blogs, private lectures, and other musings of the individuals who directly create those valuable companies are all available for anyone with the curiosity to find, read, and analyze. This is probably the first time in history that such a diverse and detailed collection of personal notes from the entrepreneurial & capitalist classes has been readily available.

Love it or hate it, you ought to at least study it.

Stitching different perspectives together and reading between the lines reveals a set of effective, if sometimes unpalatable, strategies & tactics for building generational Wealth, at the corporate level, yes, but also at the national level — reframing mainstream perspectives around macroeconomics & central banking to place the company itself at the center of the analysis.

Macroeconomics for Tech Employees: A Summary

Part I: How The Most Valuable Companies Are Built

Generational Tech companies are built on the back of:

(i) Centralizing value creation,

(ii) Commoditizing their complements,

(iii) Platformizing defensively and offensively,

(iv) Acquiring sufficient market power to capture created value, escape competition, & own the market,

(v) and building the Leverage necessary to do all the above without getting their lunch eaten by a bigger fish.

Not all dollars of revenue are worth the same

Dollars that are cheap to make are worth more

Dollars that you expect to grow a lot are worth more

Dollars that come back again and again are worth more

Software is eating the world because:

Software provides a framework to turn literally anything into a Lease (dollars come back again)

Software costs ~$0 to deliver to a customer (cheap to make)

Software can be sold instantly into a global marketplace (expect to grow a lot)

Part II: Macroeconomic Russian Dolls

~All meaningful metrics have fat tails. All of them. Mainstream coverage completely fails to appreciate the skewness of these tails.

The top 2 nations generate multiple times more economic production than nations 3-6 combined

Within all these nations, the best companies are worth multiple times more than the rest

Company value is a proxy for the complex intersection of future revenue, profit margins, customer retention, etc.

The cynical read of this is that the median individual/company/nation contributes very little to the economic Wealth & security of the whole

The optimistic read is that you can bootstrap a whole national economy with a single mega-corp (and cannot without one)

Wall St. analysts frequently compare the value of a company’s stock to the company’s periodic earnings potential — a “P/E ratio”

We can do something similar for companies and nations!

& observe that the smaller a nation is, the more valuable its biggest companies are relative to its own GDP

Part III: Case Study Takeaway: All Great Companies Sell Into The Same Global Market

Every massively successful corporation is following the same playbook

Tech is not unique at all, simply better-by-default at everything that makes great companies great

To be great, you must find a way to interface with the globalized marketplace, and then follow Rules (i) → (v) described in Part I

Part IV: Company-first Macro-economics

The bundle of macroeconomic policies that are chosen, in a well-functioning state, will be actively determined by the underlying type of economic activity that brings wealth into the state

Government spending to Stimulate the economy is analogous to Dilution at Tech companies

CEO & Board meet once a quarter and jointly agree to print pieces of paper and give them to new-or-existing employees to entice them to work (harder)

If the work they do ends up being valuable, then the pieces of paper end up being worth a lot

Literally borrowing from the future to pay the present

Tech companies pay the present in “Shares”

If the work fails to generate value, then all the existing Shareholders were diluted for no gain and see the relative value of their Shares fall

Governments pay the present in “Dollars”

As with Tech companies, if the value doesn’t materialize, the Dollars don’t go so far

Interest Rates and private banks mediate this process due to general & self-admitted government incompetence

Part V: The Federal Reserve & Current Affairs

Printing your way from Zero to One is part of the magic of the modern system

But you do have hard limits on your growth potential

At the extreme end, these look like: how many lines of (good) code your team can write per day, how many calls your sales team can take per day, and how many potential customers are out there right now

If your lens is that the Fed is master of the national economy, then you must reconcile the modern problem of stagnating economies under expansionary policies

Ultimately, the more powerful you think the Fed is, the more you’ll tend to blame them for national economic woes

But if your lens is that the Fed is merely a weatherman, who communicates the latest known state of underlying affairs to a broad audience, then there’s nothing to untangle here

Don’t shoot the messenger. This viewpoint is also healthier for your personal agency — blaming other people can be fun, but it doesn’t get you out of the hole. Only building great companies can do that

Conclusion: I Code Therefore I Am

Wrapping this all up, you can understand the company-first view of macroeconomics by starting with two questions. First: what is being built, where, and by who? Second: what is being sold, where, and to whom?

Everything is downstream of those two questions, from tax policy to interest rates and unemployment

And it’s nested Russian Dolls all the way down: the strategies that make a company successful are transitive to the strategies that make a whole nation successful

Why Do People Care About Macro?

What do I mean by “Macroeconomics”?

Macroeconomics is the study of whole economies…What makes the business cycle fluctuate; what makes economic growth go up and down; how are prices determined; what is the rate of inflation, and what determines it; what is productivity growth; and what are the determinants of productivity?

- says the Fed…

For example, using interest rates, taxes, and government spending to regulate an economy’s growth and stability.

- adds Wikipedia…

Macroeconomics attempts to measure how well an economy is performing, to understand what forces drive it, and to project how performance can improve.

Macroeconomics deals with the performance, structure, and behavior of the entire economy, in contrast to microeconomics, which is more focused on the choices made by individual actors in the economy (like people, households, industries, etc.).

- concludes Investopedia. Alas, if you’re looking up what Macroeconomics is then you may not know what all those bold parts are either.

If you wish to be “informed” — and be-seen-as-informed — this is the stuff you ought to brush up on. Next holiday season you’ll likely get more respect from family members if you share a nuanced opinion on the intersection of the money supply, inflation, and productivity statistics in the face of the ongoing pandemic than if you just mumble “Government [Good/Bad]”.

Of course, if you’re a smart Tech employee you probably understand that there are two kinds of learning: learning to pass the test/interview, and learning to understand. The first kind unlocks access to gated communities. The second kind helps you build stuff. Both are often necessary for a successful career — it’s on you to work out when you need to simply pass a test vs. when you need something deeper.

This essay is for the second kind of learning — and it’s targeted at people who build software (& software companies) for a living. It will probably not help you very much at the dinner table.

Part I: How To Build Something Valuable At Scale (theory, corporate)

Required Reading: Building Market Leverage & The Source Of Tech Prosperity

I’ve front-loaded the homework here. Apologies. But all good lessons have required reading — the audience has to be on the same page, or the content of the lecture will be received very differently depending on who has done the reading or not. The spicy memes come later.

In chronological order:

The Cathedral and the Bazaar (Eric S. Raymond, 1997-2000, relevant sections highlighted below, and this to be read and also juxtaposed with the structure of today’s dominant Tech companies — and a curious reader might then ask why have Cathedrals proven so valuable?)

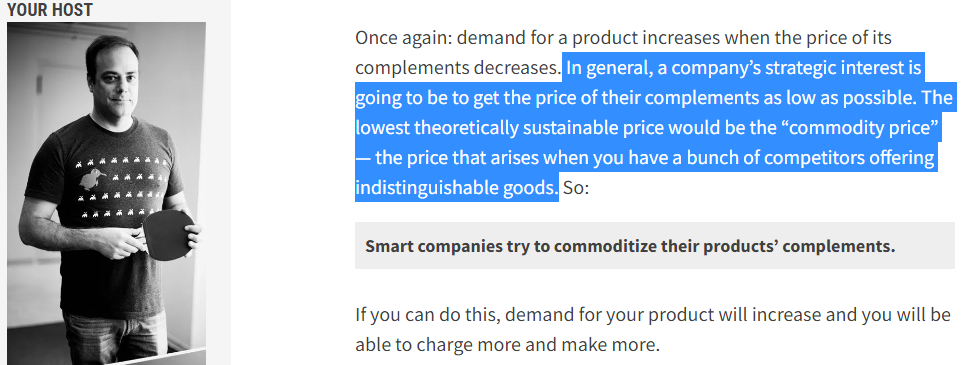

Strategy Letter V (Joel Spolsky, 2002)

Gwern’s Laws of Tech: Commoditize Your Complement (2019)

I didn’t highlight it above, but Gwern’s final paragraph above — “In practice, the division winds up being…” — is the money shot of this whole section. Vae victis.

Cliff notes for the slackers in class:

(i) Centralize value creation beneath your own roof,

(ii) Commoditize your complements,

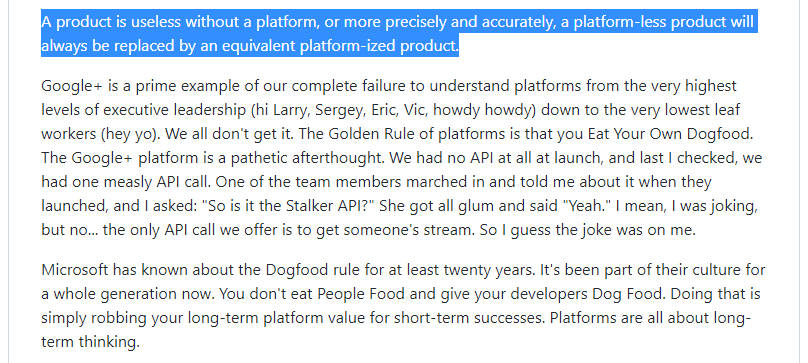

(iii) Platform-less-products are always replaced by equivalent platformized products,

(iv) Capture value, escape competition, own the market, & nobody ever thinks about distribution,

(v) Division & distribution of revenue between the thousands of individuals who had a hand in making a product is entirely down to the leverage each individual has.

Economics is, of course, the study of scarcity. And scarcity is the only form of leverage there is — everything else rolls up to it.

All the above reading was about how to build a successful & enduring Technology company.

How does it relate to Macroeconomics?

Two ways:

If you can work in and around Technology businesses without building a mental framework for how large & complex institutions create & capture value for themselves, their employees (that’s you!), and their shareholders (hopefully also you!), then you’re going to struggle to appreciate how their methods generalize. Understand your house before trying to understand your neighbourhood.

The scale of these Tech businesses competes with some national economies. This is not an accident, nor is it unique to today’s Tech sector. The core principles apply equally well to national economies. Economics is economics, and what works to build a trillion-dollar company also works to build a trillion-dollar economy. The “Engineer-First” lens of national economics begins with understanding the dominant companies within each nation — the companies are the economy.

As we will see soon:

Interlude: Not All Revenue Is The Same: Why Investors Like(d) SaaS Companies

If you work in Tech, you’re probably aware of broad trends in the industry — one of which has been the explosion of SaaS businesses (Software as a Service) in the 2008-2015 era.

Why do/did investors (and founders) like SaaS models so much? You can read about it if you like, but one simple high-level reason is:

Not all dollars of revenue are worth the same.

SaaS revenue is revenue that’s coming back. Consistent revenue from each customer means your sales & marketing teams can spend (almost) all their energy going after new customers, instead of trying to win more dollars from people who already like your products.

You could — and people have — write a book about all the downstream impacts of this, from distribution (less lumpy), to product release schedules (faster), to product quality changes (more responsive, but also more resume-padding releases), to company org. structure changes (you must now care about “retention” and build teams to manage it).

The “Service-ification” (Servicification?) of Software is just one part of a much bigger trend: everything that can be Leased, will be. Recurring revenue is that good. One lens to understand why “software is eating the world” is that software wraps ~all products & services in a tailor-made Servicified package, whether those products/services are consumer-purchased songs or business-purchased design tools.

Software provides a framework to turn literally anything into a Lease.

I’m going to assume readers know all or most of this. The important part is that none of the high-level reasons why Servicification is valuable have much to do with software itself.

Dollars that come back again are worth more than dollars that don’t.

There are of course many other reasons that some dollars are more valuable than others. Most often: Growth Rate — nobody can predict the future perfectly, but some [revenue streams] grow a lot faster than others and Margin — if it costs you $0.95 to make $1.00, you’ll only have $0.05 left to reinvest or take off the table, and that’s worth a whole lot less than a dollar that only cost you $0.50 to make.

In summary:

Not all [revenue streams] are the same

Dollars that come back again are worth more than dollars that don’t

Dollars you expect to grow a lot in the future are worth more than those you don’t

Dollars that don’t cost much to make are worth more than those that do

From a generalized principle view, if what you’re producing & distributing is valuable and can be made at attractive margins, Leasing will tend to serve you better than Selling. (and if it’s not valuable, you should sell it all at once and invest the money into something that is)

For Tech/Software, those 3 bullets translate to:

Cloud software means you only ever have to Lease access to content, products, or services to your customers — forcing them to build a recurring relationship with you to get service

You can distribute software near-instantaneously anywhere on Earth (and within 3-20mins to Mars), which means anything that achieves Product-Market-Fit can go from zero to ~5 Billion internet users…instantly

Selling additional software copies/access only costs some extra computing-power, which means you get to keep a very large percentage of every dollar (that you can then reinvest in growth!)

How does this tie back to (international) macroeconomics?

Part II: Macroeconomic Russian Dolls (data, international)

Comparing Nations: Apples to Oranges aka The Data Part

A core thesis of this essay is that you need to understand the components of a system first in order to understand that system. When thinking about companies, that means thinking like a company — not like an employee, or a consumer, or a wannabe-regulator.

My hope is that by this point in the essay you have some inkling of what it takes to build and run a successful Software company.

If so, then the rest is simple analogy.

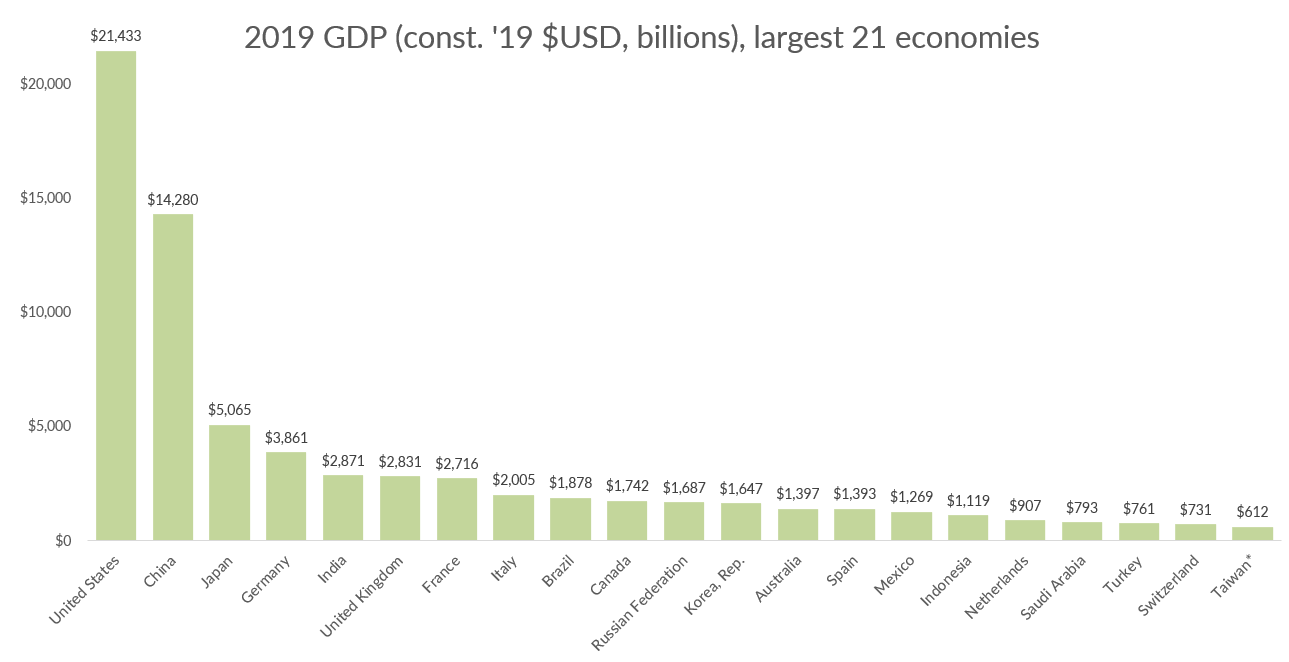

First, consider the GDP of the largest 21 national economies:

*I was going to do the top 20, but my data source is the World Bank and they can’t call Taiwan a country for reasons of utmost diplomatic importance. When I saw Taiwan would be #21, I felt obligated to include them. Also, they make for a fantastic case study, as you’ll see shortly…

This chart is important to internalize, both the absolute magnitudes (that means $21.4 Trillion!) and the relative rankings (how many United Kingdoms make one USA? My ancestors shed a tear). This chart represents, sort-of, the sum total economic product of each country — measured in dollars-per-year.

For the purposes of this analogy, treat this chart as an array of 21 [revenue streams].

But even though we’ve got them all in dollars-per-year, we know now that: not. all. revenue. streams. are. the. same.

How, then, are we to tease apart what’s going on in these revenue streams? Are the dollars in each stream to be Valued the same? Of course not.

You could divide each one by the number of people living in each country, creating an abomination known as “GDP-per-capita” — my candidate for the worst, most tortured, sordid, simultaneously abused-and-abusive metric ever publicized. No, we’re not going to do that. “S&M” stands only for Sales & Marketing in this essay, so I’ll have to save a further discussion of “per-capita” metrics for a more risqué time.

No, we’re going to work like a proper engineer and dive deeper into every single country to show some specific things about the Value within their economies.

United States

These are all Tech companies for a reason. See above. Data as of December 29th, 2021 source

Apple is the most valuable company in the America, with a market cap today of ~$2.9 trillion. That number represents the public market’s current estimation of Apple’s equity, which — as best as you’re gonna get — takes into account all the factors discussed above. Potential for recurring revenue. Growth expectations. Ability to capture high margins. And much more.

Capital markets may be efficient, they may not be, but either way the price of a publicly traded company is the best, simplest, cleanest way to Value its [revenue stream].

Note: Apple’s $2.9 trillion market cap is ~6.2x the value of the 10th ranked public company, Visa. These are not normal distributions.

$2.9 trillion also represents 13.7% of US 2019 GDP. Of course these numbers are apples & oranges — one is a snapshot value of a single company, the other is the sum total of all economic product in the whole country (a revenue stream). Dollars vs. dollars-per-year. Very different denominators, and yet linked by the simple core idea of Finance: the Value of an asset today is related to the Value of all its future cash flows.

When I compare today’s Value of Apple, in dollars, to US GDP, in dollars-per-year, I intend only to point out that this implies one thing:

Today’s value of the expected future cash flows from a single California-based company, with 154,000 employees, is equivalent to ~15% of the annual economic activity of a nation of 331 million people.

Without judgment on the righteousness of that fact, understanding its truth is helpful for contextualizing the current-and-future value of a single company relative to its own nation.

I trust most readers are familiar with the names on this list, but to summarize what the other named companies on that chart do: i) consumer tech, ii) business tech, iii) search/ads/cloud, iv) consumer retail & cloud computing, v) cars, vi) social media, vii) semiconductor design, viii) diversified investments, ix) health, x) credit cards. Tech, tech, tech, and more tech.

When it comes to America, this might be trivial, boring, and well-known. But knowing exactly what the most valuable companies in a country actually do is crucial to understanding that country’s economy — we are all downstream from these behemoths.

And, as always, we are not special:

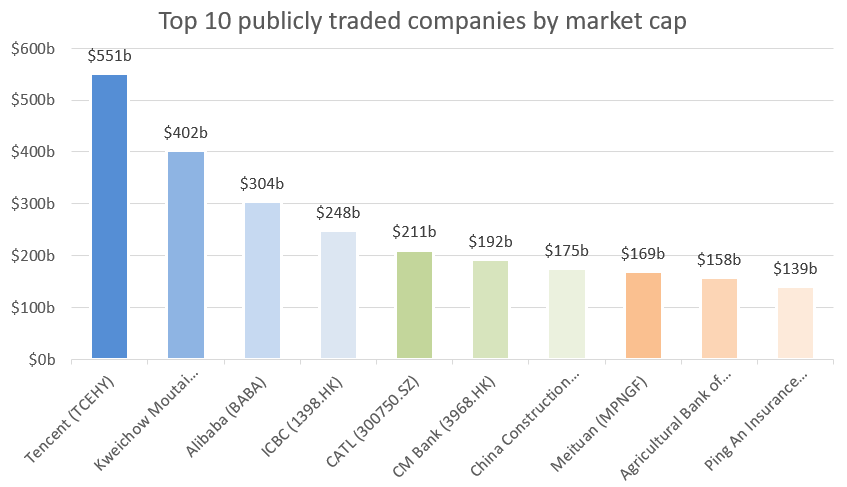

China

China’s companies have taken a brutal public-market beating lately, but Tencent still stands as the most valuable of the lot.

At $551 billion, Tencent is worth 3.9x the 10th company on this list, Ping An Insurance. Again, nothing normal about these distributions.

$551 billion is also only ~3.9% of China’s GDP. Notably smaller than the Apple::USA ratio.

What do these companies do? i) gaming, ii) liquor, iii) e-commerce, iv) finance, v) electric car batteries, vi) finance, vii) finance, viii) consumer tech, ix) finance, x) insurance.

The inclusion of finance here — four times — is noteworthy. When you see “finance”, always ask: what is being financed?

A bank itself contains no economic production (never say this around a banker in public & do not tell my banker friends I said this): it supports others’ production, allocating and approving capital to projects as it sees fit (or, in nations like China & the USA, as it is directed to by the state).

The inclusion of four banks on this list — China’s “big four” — should signal that there’s a large amount of economic activity in China requiring significant financing. Large scale construction, small scale construction, industrial factories, high-speed rail…you get the idea.

Why do none of those companies make this list themselves? If you did the required reading, you’re hopefully thinking about Airlines vs. Google right now. Rule #4 of building successful Tech companies: capture the value you create. To quote myself from above:

(vi) Division & distribution of revenue between the thousands of individuals who had a hand in making a product is entirely down to the leverage each individual has.

Economics is, of course, the study of scarcity. And scarcity is the only form of leverage there is — everything else rolls up to it.

Capital is scarce. Labor is plentiful.

Economics sorts out the rest.

The micro shapes the macro, and is in turn shaped by the macro.

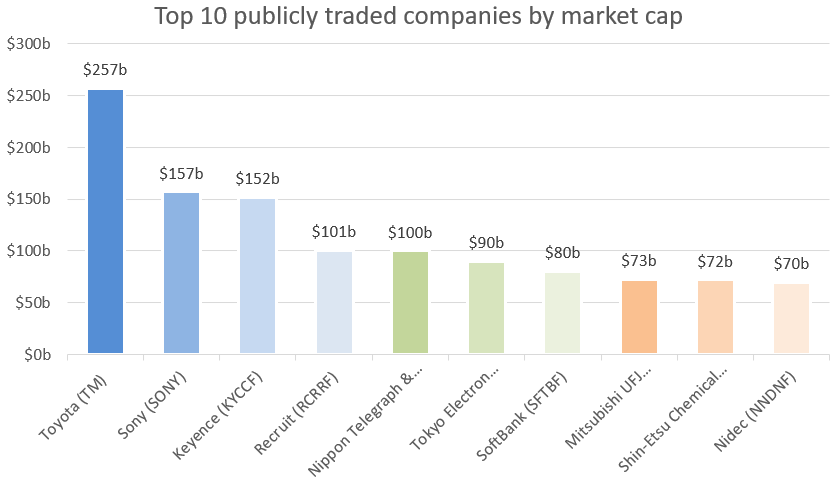

Japan

Toyota’s $257B is ~3.7x the 10th company, Nidec.

It’s also worth ~5.1% of Japan’s GDP.

What do these companies do? i) cars, ii) electronics, iii) industrial automation, iv) staffing, v) media, vi) semiconductors, vii) conglomerate, viii) finance, ix) chemicals, x) electric motors.

Industry, industry, industry, and more industry. To state the obvious: these companies make things. or help people make things. Rule #3:

Platformize defensively and offensively. Platform-less products are always replaced by equivalent platformized products

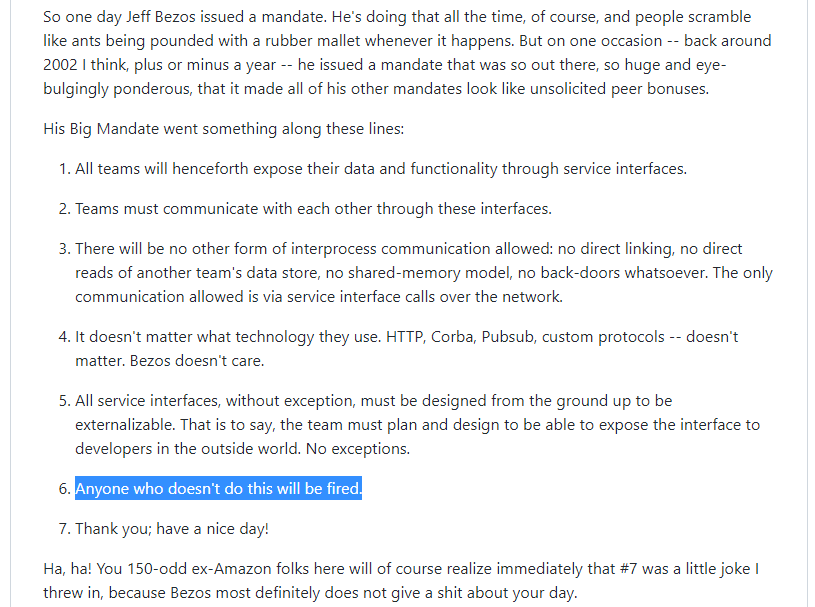

If you know how Tech works, you probably know that Microsoft offers a mega-suite of Enterprise software, end-to-end, cloud-to-client. If your business needs it, Microsoft can will provide it. Why? Because any other vendor of enterprise software is a potential entry point to your entire stack. That is the core lesson of Platforms. Steve Yegge’s required reading on Amazon’s strategy covered Bezos’ plan to turn Amazon into a full stack offering of plug-and-play components to run the whole internet. The reasons why are the same:

You must cover the whole playing field.

But these lessons apply beyond Tech. It’s not an accident that Japan’s best companies are all industry-adjacent. What would it look like to Platformize industry? If that sounds odd to you, it’s only because modern economies draw strict, strict lines between the national-government and the corporate-government:

Just read the f’ing book

A nation that can provide an economic platform is less likely to be displaced than one that only provides a single component/product.

It’s easy to get confused here. Are you supposed to be thinking about the national level, or the corporate level? Bureaucratic policy or corporate strategy? Which level owns the actual platform? To increase your confusion, allow me to point out: the Mitsubishi you saw on the chart above of valuable Japanese companies, ranked 8th, has 168,000 employees, $2.5 trillion in raw assets, and has never made a single car.

It’s actually the world’s 2nd largest bank holding company.

How come it has the same name as a famous car manufacturer?

Well you see, after the U.S. dropped 2 nukes on the country and accepted its unconditional surrender, the partial de-industrialization of the entire nation was a top priority. You can read a book on it or simply browse Wikipedia:

…in the end only the 11 largest companies were dissolved.

“-only-”. Remember, fat tails, always. I’m not trying to be too spicy here, but I do want to connect the dots explicitly here. The dissolution of the largest 11 enterprises in the nation into smaller companies, each with their own smaller turf, was a strategic priority of the occupation.

What does that imply about the relative value and the relative profit-making potential (aka Leverage) of the original Platformized enterprises?

Note: these companies were banned from coordinating — aka forced to compete, see Rule #4 — until the Allies needed “a stronger industrial base in Japan.” The companies were allowed to “coordinate” again in 1952, not because the Allies wanted them to earn more profits, or extort customers (themselves), or exercise undue leverage over the market. No, they were allowed to “coordinate” again simply to increase production.

What does that imply about the productive efficiency of Platforms vs. balkanized, standalone, competitive, single-product-focused companies?

Combine this note with Thiel’s required reading:

Perfect competition thus preempts the question of value; you get to compete hard, but you can never gain anything for all your struggle. Perversely, the more intense the competition, the less likely you’ll be able to capture any value at all.

If you want to critique the exploitation of a population at the hands of amoral & exploitative industrial tycoons, there’s a whole body of literature to support your points, & I can point you towards some good stuff if you like. But none of those points change the fundamental rules about building massively successful companies — and the rules for building those companies are transitive to building nations.

Pictured: nations and companies, Japan & Mitsubishi, America & Apple

To be clear, Mitsubishi’s close involvement with imperialist Japan is not to be celebrated. But there’s a reason Mitsubishi was splintered into a thousand pieces and scattered to the winds, while HSBC — whose “Controversies” section on Wikipedia is 3,000 words long and mostly skips over the financing of Opium into China — remains whole.

Undoubtedly, the zaibatsu were deeply involved in the unpleasant aspects of Japanese Imperialism. But that simply provides additional public support for their dissolution. The motive is much simpler than moral righteousness. The existence of an independent economic machine, generating immense surplus Wealth for its government and its people, is always concerning for the global hegemon. I’m referencing America here, explicitly — but the implication is that this model holds true for for Facebook and Apple too.

“The biggest issues is what to do about all the existing apps that sell direct today.” A-men.

If you’re curious about what ails the Japanese economy, about why they can’t seem to generate economic growth in recent history, this context is pretty important. I wrote in some detail about it last year. Rule #5 was very simple: never allow a bigger fish to eat your lunch.

Can we think of a bigger fish in the realm of Industry who has sprung onto the scene since 1990?

Back to Macro: what does Japan show us? — fat-tails, concentration of expected-future-[revenue streams] in a handful of large companies relative to the size of the national economy, the value of building a platform whether you’re a nation or a company, and not getting your lunch eaten.

Of course I’m not going to go through all 21 countries in this much detail…

(although I did, for my own edification, and you can look too if you scroll down to the Appendix)

I’ve gone into significant detail for these top three nations — America, China, & Japan— because the Pareto principle holds in all things.

In the same way America and China dwarf all the other nations when it comes to GDP, when you look within each country the same phenomenon plays out: the largest companies dwarf the rest.

Here’s the composite view, stacking all this data for every single country:

Each coloured sliver represents the dollar-value of a public company’s equity. The nations are still ordered by GDP, as before.

Eagle-eyed readers will note that some of these bars are larger than the GDP bars posted earlier.

They would be correct, although there are 2 things to remember on that front: i) the numerator is current market cap as of December ’21, while the denominator is a trailing 2-year-old GDP number, but ii) yes, some countries really are absolutely dominated by a handful of companies.

Re: i), I’ll just add that I prefer to use direct downloads from publicly sourced information, which means we’ll never get a perfect time-period tie between accurate GDP numbers and current-date-market-caps — and also that the trailing number, GDP, is relatively stable for most large economies. Lastly, I detest adjusting raw data, but you could also adjust these GDP numbers for approximate inflation data over the last 2 years to further increase the denominator.

We do what we can with the data we have — I trust you can imagine how these transformations or adjustments would nudge the bars below downwards, but not alter the story here.

Speaking of story, here’s the money shot:

click to embiggen

I toyed with showing this as a percentage or a multiple and am still on the fence. If you try and reference this chart/data at the dinner table you’ll get a lot of confused looks. Any economists still reading are likely thinking of a hundred obvious ways this is, ahem, non-standard.

And while I agree that you should not use these multiples the same way Wall St. analysts use actual P/E multiples, collectively they tell a very, very important story.

That story:

The sum market cap of the 10 largest public companies in the USA is equal to 0.63x GDP (63%)

Again, this is a relationship between the Present Value of future [revenue streams*growth*margins] and an aggregate previous-period’s [revenue stream]

There is an amusing trend from China → France where, as the economies get smaller, the relative size of the biggest companies in each country get larger (why#1?)

Italy & Brazil then ruin that trend thoroughly (why#2?)

Canada → Australia look, on the surface, to be somewhat of a return to the trend of increased concentration in smaller countries

Spain, Mexico, & Indonesia then appear to revert again…

…before shit goes completely bonkers with the Netherlands, Saudi Arabia, Switzerland, and Taiwan all having their largest 10 public companies be significantly bigger than GDP! (why#3?)

all while Turkey achieves a new low score for obvious geopolitical reasons we shan’t be covering

This is all a set up of course. The answers to Why#1, Why#2, and Why#3 are all the same. The answer is the title to Part III:

Part III: All Great Companies Sell Into The Same Global Market (results, international-corporate)

Black Gold

What does this look like to you?

Answer 1: this is all that’s listed on companiesmarketcap.com

Answer 2: this is actually an entire national economy in one picture. No lie. Ignore the big bar and you’ve got: a bank, a chemicals company, an electric company, a mining company, a fertilizer company, and a food company. Plus some more banks.

Finance (which, as we already know, means construction & infrastructure), electricity, raw materials, and food. Pretty much all the basics are covered here and it’s beautiful.

Answer 3: Leverage.

This is what it looks like when you have something everyone else wants — and by everyone else, I mean everyone. Do I even need to point out Rule #1: centralize value creation?

Today’s market is incredibly globalized, even for all the non-Software pieces. Yes, your Software can get from A to B at the speed of light. But for everything else, there’s still an international network of global shipping.

A shared Global market for goods is nothing new (read more about Mercantilism here)

Your national economy includes all the daily eggs & milk purchases people make. Monthly rent payments. Monthly electricity bills. Car loan payments. Student loan payments. All the everyday expenses.

If you’ve got a small country, those will add up to be a small amount.

If you’ve got a massive stonking country, those are gonna stack up into something huge.

But in a globalized world economy, anyone can become a serious player by selling goods into the Global market.

All you need is simple: something everyone else wants.

This is why the Tech industry is such a helpful reference. Tech goes global by default. Tech brands are household names in every developed country. Rules 1-5 from Part I make intuitive sense to anyone adjacent to the Tech industry.

Of course, Saudi Arabia has oil, not Tech, and the U.S. has shepherded them through the difficult nation-building process in order to bring that oil to market. Ask me some other time about how this is actually the greatest anti-colonialist achievement of the modern era, with the pullback from China a close second.

But all the Wealth that Saudi Arabia has comes, first & foremost, from the Oil.

The oil provides the surpluses that fund all the rest.

Using a Standard Oil logo instead of Apple’s may have been more ironic, but would’ve felt very 20th century

There are individuals in Saudi Arabia who achieve personal & familial Wealth by providing all sorts of products & services: banking, construction, infrastructure, food, electricity, vehicle imports, and so on. None of it would be possible without the Oil. This might sound obvious at first, but many people will forget it as soon as they turn their gaze towards more complex economies.

When reasoning about national economics, you can imagine the economy as a large Tech company with many sub-teams (Google, perhaps). Saudi Arabia’s electricity company may be very valuable. It may create many jobs. It may have many important stakeholders. But the Wealth of the country comes, first, from the Oil — and if the interests of the electricity company take precedence over the Oil, prosperity for the economy as a whole may be jeopardized.

Navigating these difficult waters is a herculean task — it should not surprise you to see sclerosis and special interests dominate in the long-run. Entropy always gets the last laugh.[0]

By analogy: Google’s bread & butter is online advertising (qua Search). Google has ~150,000 employees, many of whom do incredible value-add work unrelated-or-adjacent to online advertising. This is good for them and for the company. But the value of Google comes, first, from the online advertising — and the interests of other teams should be subordinated to the company’s primary Wealth-creation engine.[1]

Of course, everyone familiar with Tech will know that sometimes smaller products or teams do create far more value than the original [revenue stream]!

You really ought to have read this one…

Managing these difficult & uncertain decisions is the primary responsibility of leadership — for both companies and nations alike. The skillsets are alike.[2]

This is the fog of war that plagues leadership at the micro level — the company itself — and the macro level — the whole economy.

Silicon Gold

What about The Netherlands? Switzerland? Taiwan?

TSMC and ASML both make semiconductors.

Which makes it amusing to see two very different nations dominated by similar companies. But also: not a coincidence. Semiconductors make computer chips — not quite as good as oil, I agree, but still very necessary for building a modern technologically-enabled industrial economy.

Which means…the whole world needs it.

“Need” is a very, very important word here. Imagine all the devices in the world that need semiconductors today. Computers, of course. But also: Medical devices. Cameras. Cars. Ovens. TVs. Phones. Speakers. I’m just looking round my house at things here.

None of these devices could exist in their current form without semiconductors.

The “need” confers leverage onto these companies. They may never directly interface with an oven manufacturer. Some other company most likely intermediates that relationship. But the oven could not exist as-is without the intermediary company, and the intermediary could not exist without TSMC/ASML.

From Gwern’s required reading:

…but what is the fair division of revenue among the countless people, technologies, manufacturers who created each of the many critically-important layers in the full tech stack?

Need. Scarcity. Leverage. TSMC’s Equity value of 1.03x 2019 GDP.

The data here is imperfect and messy, because so is the real world. But the lesson is a simple one: the valuable economies are the ones selling goods into a global market. Rule #1: centralize value creation, or, more eloquently:

Make local, sell global.

Pictured this time: Saudi & Saudi Aramco, Netherlands & ASML, Taiwan & TSMC, Switzerland & [Nestle+Roche]

Part IV: Company-first Macro-Economics (conclusions, academic)

Macroeconomic Lessons: Prioritization and Stimulation

I got 5,000 words in to an essay on Macroeconomics and didn’t say “Interest rates” once. I told you this wouldn’t be very useful for impressing family round the dinner table. But I do have a few pointers.

My one “trick” for macroeconomics: always, always, ALWAYS try to understand the company-specific stuff first, all the inner nested Russian dolls…and then treat every single “macroeconomic factor” as a static output that results from this system, and not as magic wands for financial wizards to wave. To the extent that there is magic at play, assume first that it’s the Wizard of Oz variety.

Chocolate chip swirl: Who Comes First?

Modern interest in rates is ~thanks to the lifelong efforts of a guy called Milton Friedman. If you want to learn the specific details, you can listen to him talk on YouTube, browse Wikipedia or Investopedia, or buy some of his books (or his critics’ books). I’ll get to them soon.

Unfortunately, there’s a lot of politics involved in these topics, which means many interested parties:

Negative macroeconomic outcomes tend to result in unpleasant consequences politicians:

business cycle downturns lead to very unhappy citizens, mortgage foreclosures, all sorts of unpleasantries;

economic stagnation or decrease leads to feelings of uncertainty & unease among the public, fewer products & services, wariness around investments, zero-sum games, and, again, bad times for anyone who took on debt;

wacky price swings ruin the ability of regular folk & investors alike to make sound predictions, such as “should I buy 1 gallon of milk today or 2?” and “should I invest $5B in this semiconductor fab or no?”;

tax hikes hurt reinvestment & upset investors and business folk who are optimistic about the future, while tax cuts disappoint citizens who want to see more punitive correction or resource reallocation;

government spending is seen as wasteful and repugnant when done on anything the viewer voter does not personally approve of, and a moral necessity otherwise;

and unemployment is, at best, a gross waste of human talent & potential and, at worst, the primary cause of ~every revolution ever.

The politics is thus unavoidable. Don’t worry, I won’t engage in any of it.

According to my analytics page, the majority of my readers come from democratic voting-friendly political states — which means most of you will default to reading the elements in the paragraph above from the perspective of a concerned citizen. Indeed, that’s how just all the news media and politicians will talk about them. How does so-and-so relate to you, what do [horrible-outgroup] think of abc?, etc.

This may be the right framework for you & your family, but it is not the right framework for the whole team.

Putting your Macroeconomic hat on means approaching the elements above from the perspective of what is best for the country as a whole, considering the short-term, medium-term, and long-term impacts of any proposal. There is no single individual or institution in our modern democracies who has anything close to this perspective — except, perhaps, sometimes, The Fed.[3]

“Just do what’s best” is very hard to resolve when not all interested parties will win equally. Someone is Saudi Aramco (Oil), someone else is Almarai (Saudi dairy producer) — politics must resolve the tension.

The collective bundle of Macroeconomic policies you choose, across the buckets laid out above and others, will not impact Saudi Aramco and Almarai in the same way.

Therefore the collective bundle of policies that are chosen, in a well-functioning state, will be actively determined by the underlying type of economic activity that brings wealth into the state.

“The Oil comes first”, as it were.[4]

What about when a state has multiple ways to bring wealth in? What if those are in conflict?

Yes, this means more politics. But it should also mean more rigorous analysis. It should also mean generosity. A state which brings in significant wealth by value-added-manufacturing will want to adopt a specific suite of economic policies (think of Japan’s example above). If many of the raw materials used in said manufacturing are generated within-state, there’s a significant potential for conflict.

The policies that allow raw materials producers to build Wealth are very different from the one that allows manufacturers to build Wealth.

You might imagine that Value Added Manufacturers would greatly appreciate being able to source low-cost materials domestically, instead of paying high international prices for products that are some other nation’s only source of wealth, and so view it in their own best interest to maintain a healthy domestic base of raw material production…

“In this poster from 1968, a farmer and steelworker are featured with the caption 'everyday work is step towards communism'.” A pretty heavy quote there from the Guardian describing this picture, highlighting wonderful national harmony under communism. I included it for the spicy-ironic juxtaposition that follows below… — source

Alas, dollars are dollars, profits are profits, and few great businessmen ever built great businesses by making sure their suppliers earned solid margins. Consider how this plays out in modern economies — rural vs. urban, North vs. South, and East vs. West — as economic leverage leads to political leverage, and political leverage is then exercised to generate yet more economic leverage:

A key reason Platforms are valuable is they remove the need to take profits multiple times from the same transaction. A customer can enter your ecosystem at Point A or Point B, and go on to use products C, D, and E. Under one roof, the economic surplus from all this activity is retained in-house.

When the house is split beneath different rooves, no profit-oriented firm would ever allow economic surplus to “leak” out of their own borders. Altruism doesn’t make much sense when your own career could be ended by a bad quarter/year.

Rules #1 & #4 — centralize production & sell globally, acquire market power & escape competition — are not pretty when their consequences are put on public display like this. “One-third of the firms were ultimately liquidated…” Nonetheless, the geographical distribution of German firms involved in industrial production is the necessary outcome:

Good news! source

Economic leverage → political leverage → economic leverage. Forever.

To spell out the cynical take here, the fusion of business and politics is not some unfortunate bug in a complex system. It’s the foundational material of the system. Of every system. The economic outperformance of the West placed significant political pressure on the USSR (aka East Germany). The political dissolution of the USSR allowed East German resources to centralize (Rule#1) towards West German firms. Economic outcomes led to political changes which further improved economic outcomes.

You are free to ignore this whole game as it plays out. But you cannot ignore the consequences of others playing it, and the gains from ‘defecting’ in the Prisoner’s Dilemma of [Fusing Political and Economic in the present to increase both Political and Economic outcomes in the Future] are…unmatched.

If German readers feel I’m being too harsh here, they need only point at the history & actions of US companies like Standard Oil. Or, to highlight more recent Tech examples, ask yourself:

Where is Friendster, today? You know they had 115 million users at one point, right? Where did MySpace go? They made $900M in revenue in 2008, which fell to $109M in 2011, 3 years later.

An 88% drop in revenue in under 3 years on a billion-dollar-revenue company is the stuff of nightmares. Zuckerberg sends his regards

Satya may be the much-lauded CEO of Microsoft today, but don’t forget that the 2nd most valuable company in America built its foundations on crushing the life out competition via platformized integrations and legal action (Rules #3 & #5)

Over half of my readers visit my site on Chrome or Firefox browsers — you can thank the US Government for your ability to do so, Bill sure as hell wouldn’t have let you otherwise

Google was referenced in the required reading as “creating a desert of profitability” around its core business. Perhaps you can remember the distant past of the early 2000s, when other search engines existed?

I’m making my way through the list of valuable US Tech companies to help German readers feel like I’m being fair and show how Tech strategies & national strategies are alike, and at this point I’ve come to Amazon. If it’s necessary for me to describe Amazon’s cut-throat approach to eliminating any and all competition, at all levels of the business, from server farms to Barnes & Noble (rip), then there’s no hope for us. One of Bezos’ favorite aphorisms is:

“Your margin is my opportunity.”

Fear not, my German readers. We do things just the same over here in America.[5]

Relative winners and relative losers are natural consequences of changing the Macroeconomic playing field — like reunification certainly did for Germany — which is why I pound the “Understand ALL the Players First” drum so boorishly. Every policy has a consequence, intended or not.

Modern Keynesian: Stimulation and Dilution

Another name you’ll hear a lot in macroeconomic discussions is Keynes. Again, do your own extra credit homework.

To summarize unjustly, Keynes pointed out that all macroeconomic factors are linked together in a complex network, and that the central government sits at the center of that network with a big budget. Modern updates here have noted that the technical budget of $[X00,000,000,000,000]/year is somewhat relevant, but there’s also-the-ability-to-just-print-more-money-as-needed.

Thus: declines in some macroeconomic indicators can be counteracted like so:

Price adjustments occurring during the time lag between initial investment & product-launch-date means the initial investment may no longer generate positive returns →

means Loans taken out to Finance the investment may go unpaid →

means the business may enter bankruptcy →

means employees laid off and local unemployment increases →

means reduced wages & economic surplus for the local economy →

means reduced demand for products & services →

jeopardizes other businesses that touch the region →

bad times ahead →

new government in 3…2..1…

Orrrrrr….the central government could temporarily step in, spending money either directly or indirectly at multiple stages of this Failure Cascade and put a stop to the whole thing.

It’s a pretty awesome idea for anyone who wants to mitigate a short-term unpleasantry.

Tech employees should be very familiar with this idea!

If a Tech company is struggling to hire or retain employees necessary to build their business, the CEO and the Board of Directors can meet once a quarter and jointly agree to print pieces of paper and give them to new-or-existing employees to entice them to work.

If the work those employees do is valuable, then the pieces of paper will turn out to be worth a lot! You borrow from the future to pay the present. This is a unique & special power, that has to be wielded with responsibility. If it’s abused too heavily, the CEO and Board, as well as all the existing old-timers employees, will find the pieces of paper they were given in the past aren’t worth shit anymore.

This is known as “dilution”, and makes them a) very sad and more importantly b) very unmotivated to do more valuable work.

At Tech companies, these pieces of paper are called “Shares”.

At Governments, they’re called “Dollars”.

How To Print & Spend Government Money: Seriously, Have You Been To The DMV?

Of course things are never that simple. Most Governments are aware of their own ignorance & inefficiency, particularly in the post-modern post-industrial post-Bretton Woods West. Central planning is very tough and most Western governments do not select for people good at it.

But do you know which organizations do select for people pretty good at predicting future outcomes & allocating capital efficiently to ones with a chance of positive returns?

Why do banks matter for Macroeconomics and Government spending? To quote myself from a year ago:

Instead of doing all the tax-hikes/tax-cuts and Government spending yourself, a smart central government can outsource all the required analysis to banks, and then simply encourage or discourage those banks from creating more or less money “out of nothing.”

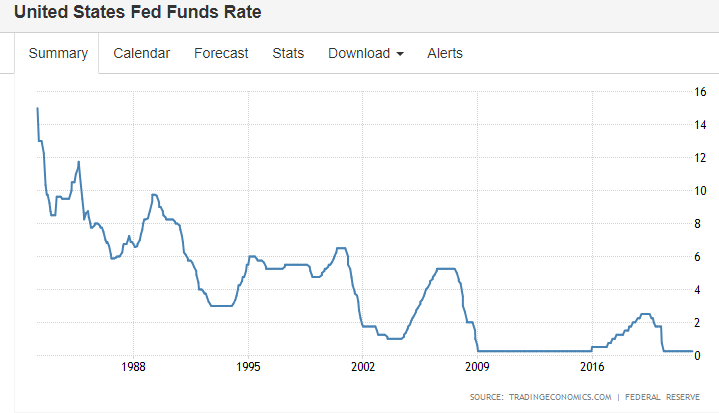

“Interest rates” therefore translate to “how much more money in the future you can get by having a pile of money today”, which ends up being the primary mechanism most modern governments use to mediate how much money banks need to “create out of nothing”.

If the Fed pays the banks a lot of money themselves (high Interest rates), the banks don’t need to go looking for businesses to loan it out to.

If the Fed lowers the money they give banks simply for keeping cash in the vault (lowers Interest rates), then banks — who care about making money more than you can possibly imagine — need to find investment opportunities instead.

In the modern system, Interest rates are the lever that unsophisticated governments can use to outsource management of the whole economy to sophisticated private parties.

A single lever to move the nation.

It’s quite beautiful.

Part V: The Federal Reserve & Current Affairs (commentary)

Why Not Use The Stimulating Cheat Code 24/7?

Why don’t they just keep rates low — or even negative! — all the time then, to boost all the investment opportunities?

Once again, we can look at Tech to understand the problem:

If it’s abused too heavily, the CEO and Board, as well as all the existing old-timers employees, will find the pieces of paper they were given in the past aren’t worth shit anymore.

This is known as “dilution”, and makes them a) very sad and more importantly b) very unmotivated to do more valuable work.

I said above that “Inflation” is either a result of insufficient supply of goods (supply-driven Inflation) or far too much demand for limited goods (demand-driven Inflation).

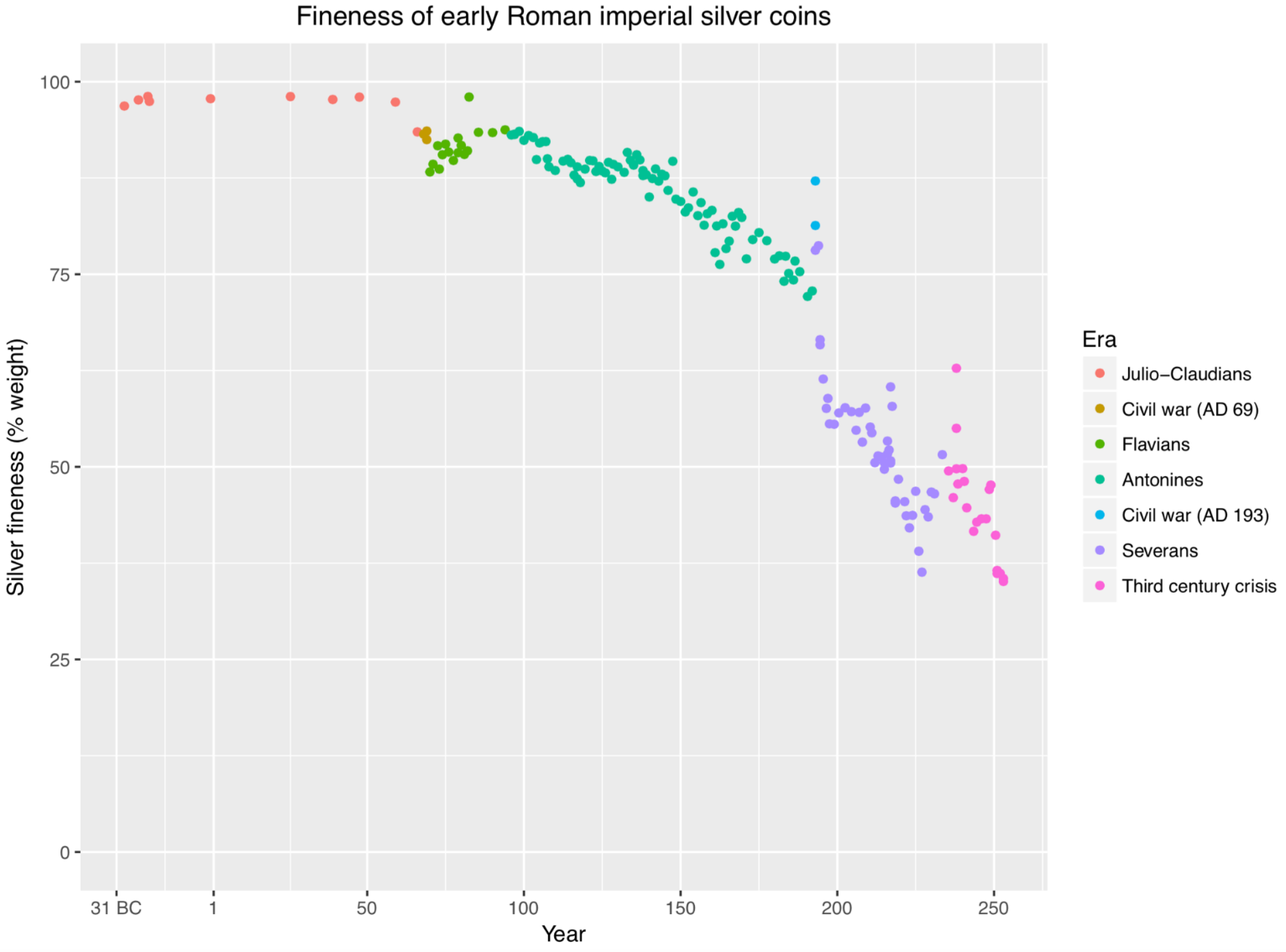

There is another kind of inflation: monetary debasement.

This is what it looks like when you, quite literally, Dilute the value of your currency source

When your coins don’t contain as much silver, they aren’t worth as much, shocker, I know. Prices must therefore rise to balance this out — a process which tends to involve some unequal latency. Well-connected institutions or individuals can often then take advantage in the time lag between debasement and price adjustment (aka the Government & friends). It’s called the Cantillon Effect, if you’d like to read more.

Monetary debasement is therefore the last refuge of the desperate & scoundrels — and all scoundrels eventually become desperate.

When banks pull money out of nothing, the expectation is that it will be used productively to create more value. Even though you — a Tech employee — might get diluted to shit every time your company raises another round of financing, the actual worth of your shares will still be increasing so long as your company is becoming more and more valuable.*

*unless you’re Eduardo Saverin, in which case lawyer up.

But there are limits to these things — hard, physical, engineering limits. At some abstract enough level, the limits are quite literally tied to “lines of code your eng. team can write per quarter” and “number of calls your sales people can take per day”.

“Well we can always hire more engineers and sales people.”

And how will you pay them?

“Out of our profitable business earnings.”

And when those run out, because surely they are not without limit?

We can raise more money from financiers

Who will dilute all existing shareholders in the process…

It’s fine, the new employees will add more value than we lose to dilution.

Infinitely? Without limit? Awesome, where can I send you money to invest in this infinitely-large infinitely-scalable instantaneously-capital-generating business!*

*pls do not invest in opportunities like this unless you know what you’re doing

Understanding the constraints to growth is why the Tech perspective on how successful companies are built is critical to understanding Macroeconomics.

If you lose sight of the concrete actions that generate “productivity”, you can end up nodding in agreement with sophisticated arguments for diluting the value of all existing currency by 75% without stopping to ask if there actually exists enough potential productivity to overcome the debasement.

But if you understand that there are always and forever underlying real-world drivers of all productivity, then the idea that “interest rates could be lowered dramatically to encourage productive investment, but no extra production actually happens!” will be neither surprising nor interesting to you.

If you have some experience with actual videogames and real genuine cheats — and also with the sort of person who tends to be bad at games — you may have rolled your eyes at my suggestion in the subheading for this section: “Of course some people are just gonna use the Cheat Code 24/7!”

I leave it to the reader to draw their own conclusions here.

(Of course I will present conclusions for you further down the page)

Note on the Desperate and Scoundrels:

I hope all Tech employees and software engineers understand the value of raising additional capital to expand the business, thereby increasing the value of the company by a large multiple and attracting more talent to fuel the machine. Some dilution is a perfectly reasonable price to pay for accelerating growth.

“Good” Dilution is Debasement — except your real personal wealth goes up. Finance is Magic.

In truly Desperate times, which I hope none of my readers ever have to experience, let alone be responsible for, there is no certain future ahead. It may not be possible to increase the value of the company at all. The company may not exist in the very near-term.

Monetary Debasement that occurs in truly desperate times involves existential questions. The second essay I ever wrote (Moloch is Our God: AI, Mankind, and Moloch Walk Into A Bar — Only Two May Leave), and one that I still frequently get positive comments on, is essentially a recognition of the necessary-but-tragic element involved in all existential questions.

So I’ll say simply that nobody who has never been Desperate and Uncertain should judge the decisions of those who were Desperate and Responsible too harshly. Heavy is the head and all that.

But do bear in mind that the genuine Scoundrels know all this — and know the leeway that is granted in such times. It’s not purely from incompetence that all Scoundrels become Desperate: though the incompetent ones end up there by accident, the competent ones swim there quite on purpose.

Boundary Conditions for the Modern Wizards

A major point of this essay is to reframe every macroeconomic indicator as an output, not an input. To view economics & finance professionals as financial accountants, not financial engineers. To use what you know about building successful companies and apply it to building successful economies — and to stop there, without sparing a second thought for the academic indicators.

And yet I just spent the last 2,000 words explaining why the Fed is the central architect of modern economic outcomes.

Can you square this circle?

When learning Calculus, you start by understanding an equation’s behaviour at the extremes. Extreme conditions show you where the boundaries are. For many problem sets, knowing the boundaries is sufficient.

Thus, I present two boundary conditions for reframing Interest Rates and The Fed:

Infinite Stasis: All economic growth stops tomorrow. All expectations of future growth stop. No new businesses are started. No new homes are built. No new technology. Complete hard stop on everything, indefinitely.

Under this scenario, what is the future value of money? What is the likely return on capital?

At first, you may think: zero.

And you’d almost be right — in a world which is defined to have no investment opportunities, the amount of extra money you can earn in the future just for having a bit of Capital, today, in the present, is ~nil.

Maybe you think you could serve as a loan shark, at least? Perhaps on the very margin. But there are no new jobs coming, not now, not ever. Anyone you loan money to today is almost certain to still be broke in the future. Out of what Wealth source could they ever pay you back?

The outcome is that nobody pays you anything for your money — because you have no reason to ever loan it out. “You” here refers to everyone, from you, the reader, to heads of state. Money loaned will not return with interest in a zero-growth environment.

Interest rates thus become “zero”, to the extent that they functionally cease to exist. There is nothing our Fed could do, one way or another, to move the needle.

And yet. The value of money does not go to zero. In a zero-growth world, asset holders are Kings and Queens. The boundary condition did not define Wealth away to zero, nor economic activity to zero — it simply stopped all new activity. If you own assets, you continue to generate Wealth.

This is a very strange world to modern minds. Excess cash becomes worth nothing, but owning productive assets becomes worth ~everything. It’s hard to imagine. What is the Fair Value Sale Price of an asset in a world where the cash itself earns nothing? Where there are no investment opportunities at all?

It approximates infinity. What could you possibly do with the cash you received? Only violence or its threat could ever justify a change of control.

In a Feudal world, only the willingness to pick up the sword separates the Lord from the Peasant…there’s only one good way to build Wealth — Take it and Tax it. Veni vidi vici etc..

In this Boundary Condition world, cash will buy you anything at all — except the ability to earn more. Anything except Wealth.

Infinite Stasis leads to zero interest rates, infinite asset prices, and all economic activity becoming consumption or zero-surplus labor.

The second boundary condition:

Infinite Progress: All conflict and political instability is evaporated. Markets and capital and labor are free to move wherever, whenever. There are no restrictions on investing in companies. New Technologies turn Sci-Fi futures into reality, on timescales measured in quarters. Twelve new Apple Inc.’s are created this year, this month. New markets are opened up and the global economy doubles in size — tomorrow. Demand for labor 100x’s, and the new technologies mean labor productivity also 10x’s. You can move to your nearest Urban Center and 10x your hourly wage, and that’s assuming you have no skills at all.

Under this scenario, what is the future value of money? What is the likely return on capital?

When contrasted to the first scenario, the answers suggest themselves.

Everyone invests everywhere. The value of money sky rockets — your Wealth could compound astronomically if you keep investing in productive businesses. The new Wealth means prices rise — ~all prices, everywhere.

Opportunity cost becomes the dominant factor in determining almost all costs.

While this boundary condition may sound — at first — like paradise on Earth, the second-order consequences of Infinite Progress will be that anyone who is not taking full advantage of the crazy new economy gets left behind. If you go live in the woods for a month you won’t recognize the world when you get back. New cities, new vehicles, new tech, new planets. Better hope your 401k was well-invested, otherwise you may need to adjust your retirement plans.

How much, then, for a dozen eggs and a gallon of milk?

How much, a month later, for the same?

How much, at that point, for a college education at Harvard?

Even if technologies have lowered the cost of milk production, the Iron Law of Rent applies to all product assets, not just land. And your cash is now a productive asset. Perhaps the milk will be free of charge, flowing from fountains in the town square — but something else, some otherwise normal part of your annual economic budget, will likely find itself bid up in price simply by virtue of the fact that everyone is now earning 10x the wages they were last month. Healthcare is a common real-world example of this phenomenon (read more here & here).

The excessive productivity leads to excessive Wealth and excessive investment opportunities, which both put excessive upwards pressure on almost all prices. Note, though, that a simple house may appreciate in value less quickly than other more productive assets in this time.

This scenario feels harder to me to model out, as it’s so far beyond anything I can imagine. Perhaps I am misjudging some of the particulars here. Nonetheless, I think it’s obvious that this world would look VERY different from the Stasis scenario — and that our hypothetical Fed would need to adopt a radically different policy in response.

Infinite Progress leads to high prices for productive and consumptive goods alike, many investment opportunities, and correspondingly higher interest rates. All asset prices rise due to the Iron Law of Rent, but the productive assets rise in price most quickly.

I don’t want this to seem too academic and disconnected.

After touching on all these various topics, let me try to tie them together with a simple question: how much money should the government of Saudi Arabia sell Saudi Aramco for? The whole company, not just 5%. Complete divestiture.

“Well you see, that’s simple, just calculate the net present value of future cash flows-”

Don’t be silly. To sell the entire company — a company which, as I’ve laid out, is responsible for the entire economic well-being of the country — would be ridiculous. The asset in question sits at the foundation-layer of the modern globalized industrial economy. There are not many more-productive areas the Saudi Government could choose to invest their sale proceeds in — and they’d end up with less Leverage over whatever they pick than they currently have with Saudi Aramco.

What competes with Oil in terms of value and leverage? You can scan the company names from Part II to find out. Tech. Industry. Pharma. The problem is not just that these are hard sectors to spin up from nothing — it’s that there are already entrenched globalized suppliers in each of them. The Saudi government would be divesting a ~centralized asset, around which it controls a global cartel that limits commodification & has built sufficient market power to capture ~all the value created, and on top of which it is able to exert enough leverage to earn the protection of the largest navy on Earth. In exchange for what? Competition with Chinese and Japanese industry? Or with Chinese and American software developers?

Ridiculous.

At the pinnacle of value-creating assets, the world really can start to look a little Feudal. All other investment opportunities will make you poorer.

What could you possibly do with the cash you received? Only violence or its threat could ever justify a change of control.

Since most readers are not members of the Saudi Government, there’s a way to reframe this question much closer to home:

How much money should your CEO sell the primary revenue-generating engine of the company you work at for?

It’s nesting Russian dolls all the way down. The easier it is to come up with an answer, the faster you should probably start interviewing for a job at FAANG/MANGA:

House motto: “We do not sell.” source

The Fed As Weatherman: Don’t Shoot The Messenger

The two scenarios of Stasis & Progress are of course completely unrealistic.

But the boundary conditions tell us about the expected behaviour of the system — and about the likely directions indicators would move under growth or no-growth environments.

I poked some cynical-lighthearted-fun at the hard-working people at the Fed earlier when discussing “cheat-codes”. But if we reframe the Fed (& other Central Bankers) as downstream of real underlying economic activity — merely reacting to it and communicating that reaction to the masses market — then the picture looks quite different.

I do not mean to downplay the importance of this position either — as I write this, New England is enjoying the worst winter storm in four years. Thanks to some notice from the weathermen, we went shopping yesterday (along with half the town). Food for a few days, full tank of gas, candles, fresh water. Our physical and economic activity was directly driven by the weathermen.

But the weathermen did not summon the storm.

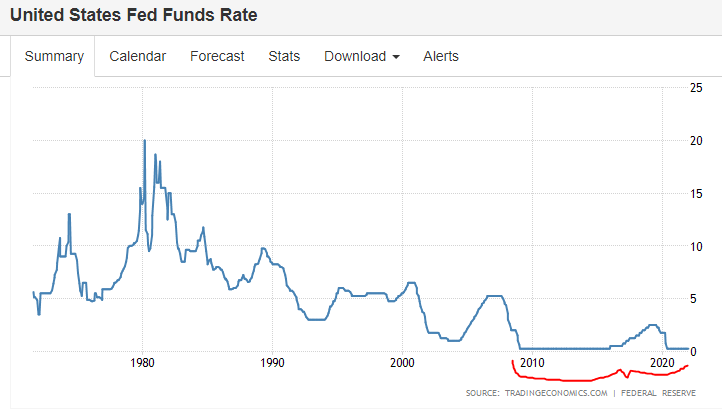

And so, in defense of the Fed, I simply present the exact same chart as before, only this time with the new context that they may be in the passenger seat, not the driver’s seat:

If your browser settings are similar to mine, these charts should ~line up with each other. The start date for each is the exact same.

Readers have chastised me for drawing on charts in red marker, so I’m trying not to overdo it here. I use the fuzzy hand-drawn red ink to call attention to things that might otherwise go unnoticed — we all see so many charts every year that we tend to only see what we expected to see.

But if your lens is that the Fed is master of the national economy, then you must somehow reconcile the problem of easy money and low growth: The rates have been kept at zero since the Great Financial Crisis (even negative in some nations). And yet the actual economic growth — GDP growth rate above — fell ~2% short of what we experienced for 25 years, and stayed there from the GFC through to the Corona-crisis, all while many prices have soared (assets, college, healthcare, housing).

Obviously the corona issue really tanked things in 2020, so 2021 has seen a somewhat anachronistic bounceback. Perhaps 6% growth will be the new normal and we will return to the glory days of old. I hope so. Perhaps it’s all “inflation” and downstream of pandemic-response measures. I hope not.

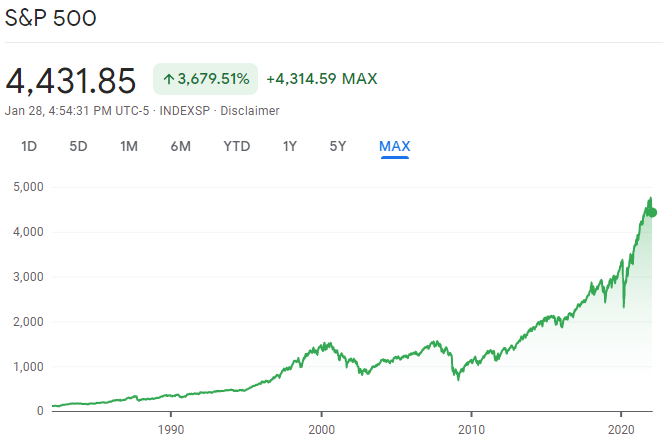

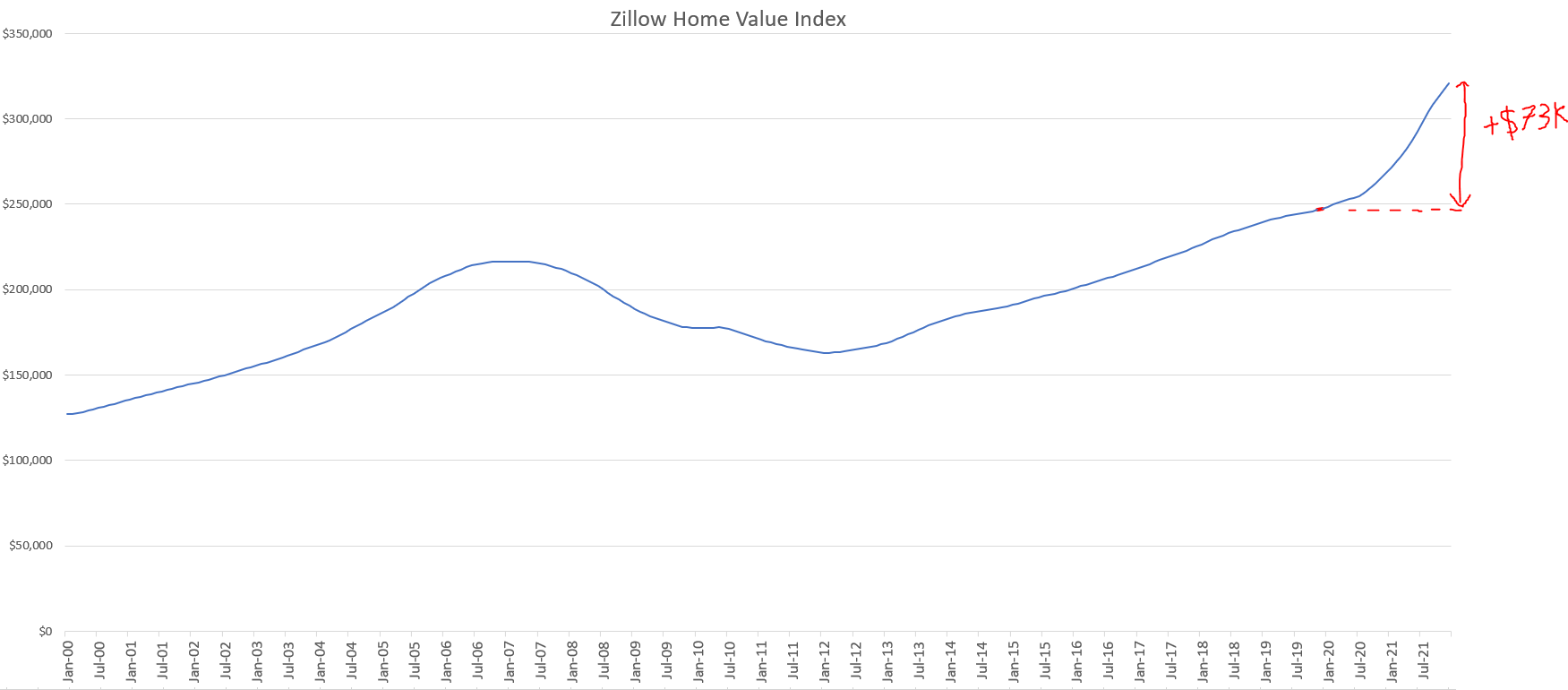

But if your lens is that the Fed is in the passenger seat, then there is nothing to untangle here. Economic performance has not recovered since 2008. Growth expectations are perhaps permanently lowered. Interest rates have bottomed as a result. Asset prices have skyrocketed:

The time period on the x-axis above exactly matches the 2 charts above, to the day. Scrolling up/down should link them together if your browser settings are the same as mine

Note the x-axis on home value here is not linked to the previous 3 charts — Zillow only provides data since 2000, and the current data is through December ’21. Average home value increases over the last 2 years were equal to Home Value increases in the 6 year period between May ‘13 → Dec ‘19 source

“Low economic growth, low interest rates, astronomical asset prices” — of the 2 boundaries discussed earlier, I know which one this is closest to.

4% economic growth or 2% economic growth, is such a difference really so huge? Who knows.

$100 growing at 4% for 25 years — a generation — years turns into $267. $100 growing at 2% for 25 years turns into $164. A difference almost exactly equal to the principal.

Form whatever opinions you like about the political outlook and economic attitudes of Millenials and Zoomers, just make sure this is a factor in those opinions.

The unfortunate and genuinely pitiable situation of the US Federal Reserve is that they have a dual mandate:

It’s time to d-d-d-duel source (Official Fed website)

They must attempt to keep unemployment low and prices stable. The 2 boundary scenarios I presented above were an attempt to show how these two goals are linked.

Lots of growth → prices rise ( → Fed can raise interest rates to combat prices/inflation).

Low growth → (low jobs) → prices low → Fed can lower rates to combat lack of jobs (by making investments more attractive).

But WTF is the Fed supposed to do when low growth is caused by limited investment opportunities and not a lack of capital access??

If they lower rates to combat the low growth environment, prices will go up, up, and up. But if the reason for limited growth is structural, extra jobs may not materialize! Economic stagnation under conditions of price inflation. Stag-flation (this wiki article has a surprisingly good summary of competing views on the topic).

This is the frustrating situation that The Federal Reserve finds itself in today. The factors that shape their decisions have been discussed by academics for 50 years now. They are not new. But the media that analyzes their actions, and by extension the public at large, has absolutely no understanding of the causality at play.

“Inflation high? Better raise rates or you’re being politically motivated cheat-code exploiting hackers.”

But raising rates is likely to lower incentives for investment and somewhat reduce employment, with spillover effects on economic growth. Their hands are tied.

The dual mandate has an inner tension. The Weatherman gets blamed either way.

To mirror the question above: how many shares should your CEO print & sell to new investors (for cash) & employees (for hard labour) when nobody is interested in buying your products? None? But then how will you fund the development, production, and sale of new and attractive products? Lots? But then all existing stakeholders will be diluted based on…hope. Promises with no punishment for breaking them (besides the dissolution of the company). Either way, the blame for negative outcomes will roll upwards:

Pictured: your boss, your investors, your customers, you & your fellow employees, and some journalists (back right)

If this question seems too hypothetical for you, ask why Box.com’s CEO owned a mere 5.7% of the company when it filed its S-1 in 2014………compared to Zuckerberg’s 28% stake in Facebook, Elon’s 28% stake in Tesla at IPO, or Bezos’ 48% stake in Amazon at IPO. Or, to use a more recent example, ask why a certain Michael L. Speiser personally owned 20% of Snowflake at its IPO, while his own venture firm owned another 20% (page 119 of the S-1 I linked — if you work around enterprise Tech, you should really know about this last one).

The number of shares they had to print along the way to IPO tells you how quickly the company was able to build a valuable business. So for most Tech companies, the percent of the company that your CEO owns will also be a proxy for the value of your own equity as an employee.

Economics-literate readers may already be well-aware of the delineations in this essay between “standard” and “less-common” views, but just to make it clear for all readers: all the above is well-trodden ground. There is nothing heterodox in me highlighting the problems that plague central banks, I’m just explaining things that you could otherwise learn in a textbook.

The one vaguely-heterodox macroeconomics opinion that I’ve woven in throughout this essay is that “structural” reasons for limited growth opportunities are, in many times and many geographies, often the norm. You can get there from a global pandemic, yes. You can get there from a massive reduction in a necessary economic input like Oil, yes. But you can also get there from the normal conditions of doing business in a dynamic economy.

You can get there simply because someone else ate your lunch. And you can impose them on your competitors, national or corporate. These opinions are informed by reading (The China Shock, National Bureau of Economic Research, Autor, Dorn, & Hanson) and writing (The Germany Shock & Unequal Growth, both by myself). And, at their root, these opinions are all downstream of my own experiences in and around Silicon Valley’s Tech economy.

At the national level, which can simply be the level of your nation’s largest companies, any violation of Rules #1 through #5 can leave your central banks stranded in the no-growth twilight zone.

Have some sympathy for the weatherman’s predicament, and some respect for their communications.

The gif above fits both side of this discussion depending on your religiosity

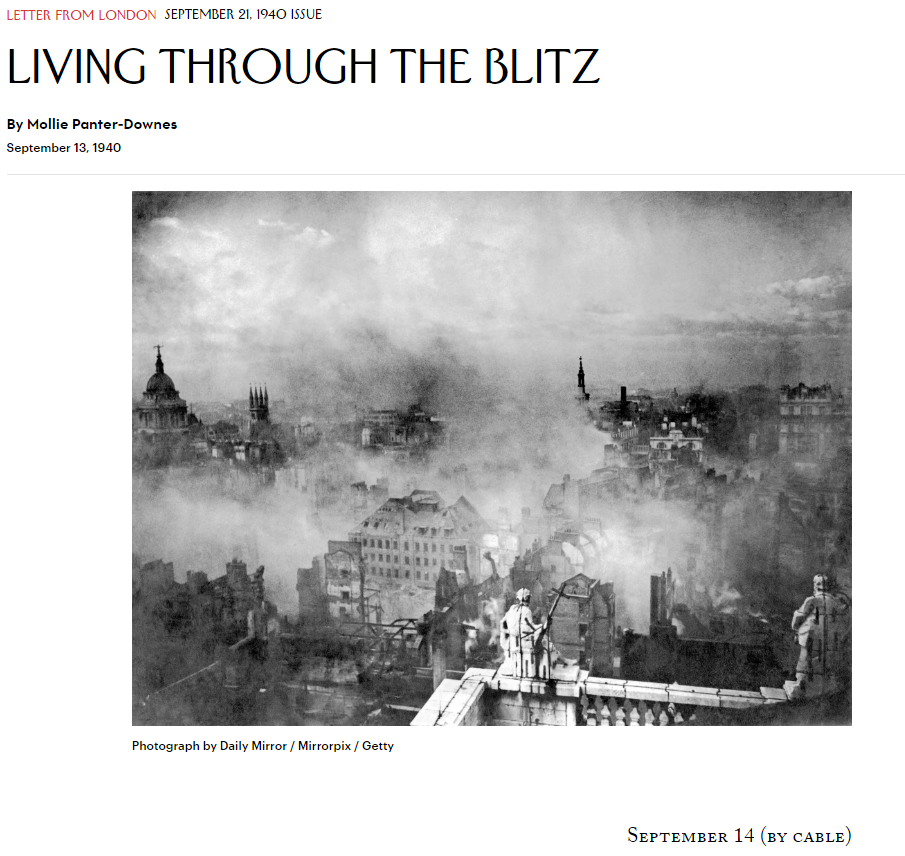

The Blitz

I didn’t include it in the required reading, because I think there are too many counter-examples for it to be truly required, and you really need to hit Product-Market-Fit before betting the house like this, but if you’ve been at all plugged into the Tech scene post-2012, you’ll have explicitly or implicitly encountered the PayPal mafia’s pet theory on company building:

But whether you’ve encountered these ideas before or not, it should be clear that they can and do work. Reid’s personal wealth is the only testament you need here.

Blitzscaling is insanely effective, more a Tactic than a Strategy, it can support a company establishing a chokehold on a market and cutting off competition. To carry the Russian doll analogy, it’s like starting with the smallest inner-most doll and then building the largest outer-most doll around it next, trusting yourself to build the middle dolls later.

Obviously, this comes with potential costs.

If you do not have Product-Market Fit, Blitzscaling will destroy your company, your reputation, and your business relationships (& perhaps your personal ones too). “The Blitz” was a German bombing campaign that killed 40,000 British civilians. “Blitzkrieg” was a surprise application of overwhelming force to dismantle France. Blitz-ing things does not result in frolicking lambs and fluffy bunnies.

The goal is to leave your competition in the pictured state. source

I leave it to the reader to consider which Macroeconomic policies may best be described as a “Blitz”, what a Federal Reserve “Blitz” might look like, and what the outcomes of running a national economic “Blitz” might be when a nation no longer has Product-Market Fit. The only note I’ll add is that a Blitz must always be total — you cannot have half your org. running a Blitz. If you’d like to study some specific examples, helpful search terms might be: Deng, MITI, & TSMC.

Conclusion & Summary: I Code Therefore I Am

The point of this essay was not to rehash lessons you can learn perfectly well from credentialed economics PhDs and/or Wikipedia pages and YouTube lectures. Go forth, watch stuff, ask questions, read books, try not to watch the news.

The point was to give anyone familiar with Tech companies a suite of viable analogies to reason about the bigger Macroeconomic picture — and to relate that bigger picture back down to their everyday work. To show how central banks manage Western national economies and to impart some respect & sympathy for what they do. And to bridge the divide between those two perspectives: entrepreneurial corporate and academic central banker.

Hopefully my examples weren’t too spicy.

Viewed one way, the financiers drive the entrepreneurs. Viewed another, the entrepreneurs dictate to the financiers.

Tech company strategy provides useful analogies for this whole situation — but I don’t mean for them to be mere analogies. Massive economies are built ~entirely on the back of massive companies. You can hate the mega-corp, you can worship the mega-corp, but if you want good things for yourself you’ll need to index your own fortune to something as economically productive as a mega-corp. Known candidates include: mega-corps. The consequences of not doing so are at best the inability to afford iPhones and Oil, and at worst impoverishment and exploitation at the hands of those who did choose to plug themselves into the global marketplace.

If I have to end on a specific note for thinking about macroeconomics and the consequences of macroeconomic proposals in the future, it would be this:

Ask first what is being built, where, and by who. Ask second what is being sold, where, and to whom.

Who, whom. That should be enough to steer you in the right direction.[6]

Notes

[0] “Macroeconomic policy” is literally just resolving exactly these tensions, all day, every day, in front of people who have no understanding of the relevant factors but who will vote/riot you out of office if you don’t successfully propagandize your policy to them. Exciting!

[1] There are many reasons Google+ failed miserably, though we should all commend the effort. My suggestion here is that Google+ failed for many small reasons, but the biggest one of all: Search was not at the beating heart of the platform. The Google+ platform ran on social, not Search — infusing every part of Google with #SOCIAL in response to a perceived external threat from Facebook — which could never withstand a confrontation with Core Google. Inside the inner-company politicking, Search wins the long-game 99 times out of 100.