Three points motivated me to write this — forming a Bermuda Triangle in which the average American’s savings disappear without any apparent cause.

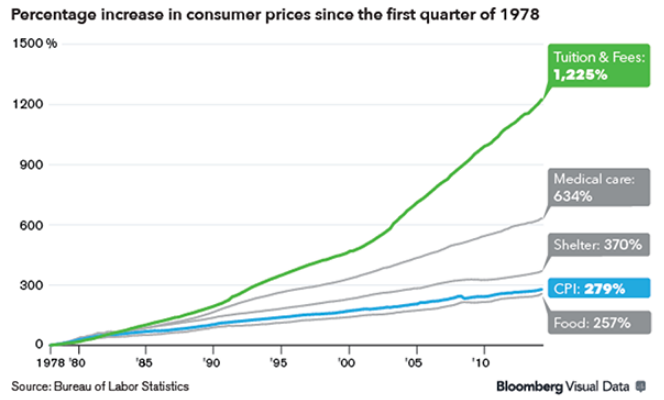

1. Considerations on Cost Disease — the observation that certain costs (Education, Medical Care, Housing) have increased many times faster than inflation, while wages in those same industries (and in all the other industries too) have remained mostly stagnant

2. Second, and on a more personal note, I’m fortunate enough to be a graduate of MIT who has worked in both finance and technology for 5 years since graduating. I’ve had fantastic employment opportunities. Nonetheless, any meaningful purchase in any of those categories above would wipe out all my liquid assets and savings and potentially require additional loans or financial assistance.

Education

For example, consider the cost of continuing my education with an MBA at the nearby Stanford (shoutout to my friends who are going / have gone already).

Note, this $120,000-for-10-months budget helpfully excludes the cost of the required “Experience Abroad” program, for which Stanford suggests reserving an additional $2,000 to $4,000 — practically chump change at this point.

Medical Care

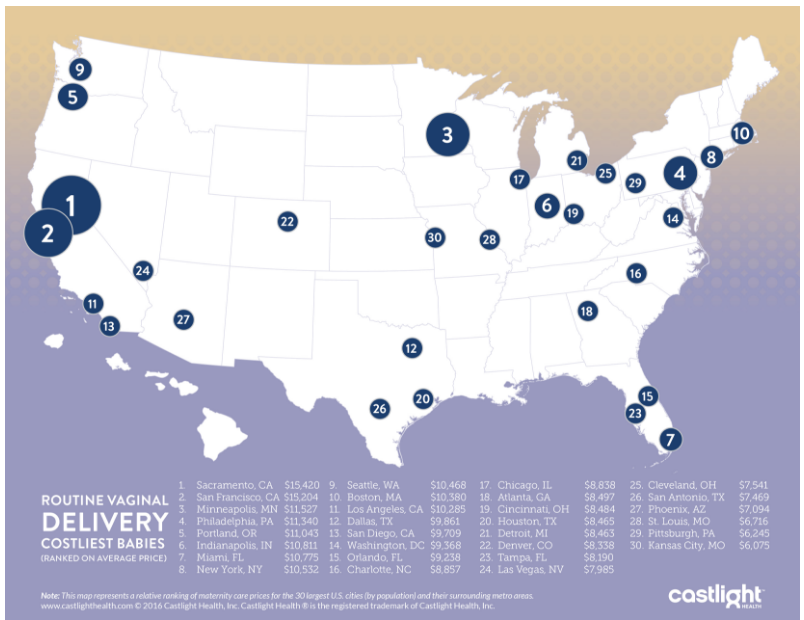

I’m lucky in that I don’t anticipate any significant medical expenses in my future, but Google tells me that the most common reason for hospitalization in the US is childbirth. Thankfully, here in San Francisco, that would only set me back $15,000, unless of course we needed a C-section, in which case it’ll be a casual $30,000. More of an “undergraduate education” than an “MBA”-level sticker price, but certainly a meaningful percentage of my savings.

Housing

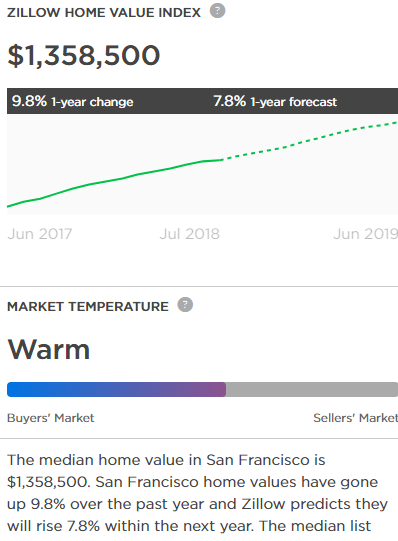

And of course, not that it needs to be said, but if I wanted to buy “Shelter” near my place of employment I’d be looking at a bank-breaking $1,358,600 purchase at the median, growing 8-10% per year:

Since I can’t afford that, I’ll just settle for renting and saving my money!

Oh. Right. The Consumer Price Index for Rent in this town is up 30% since I moved here 4 years ago. Nice. In all transparency, my rent only went up 8% this year, which doesn’t sound quite so bad. Until I do the math on another 4 years of 8% rent increases (100 * 1.08^4 = 136%) — and realize that I need a 36% increase in income over that same period just to stay flat on nominal take-home savings.

Per my first point on Cost Disease, real median household income in the US has only just clawed its way back to what it was in 1999. Certainly it hasn’t grown 36% in the last 4 years. But maybe there’s some way I can get ahead of the median? Maybe there’s some way I can keep my income going up more than 36% every 4 years and actually build wealth too?

How much was that MBA, again?

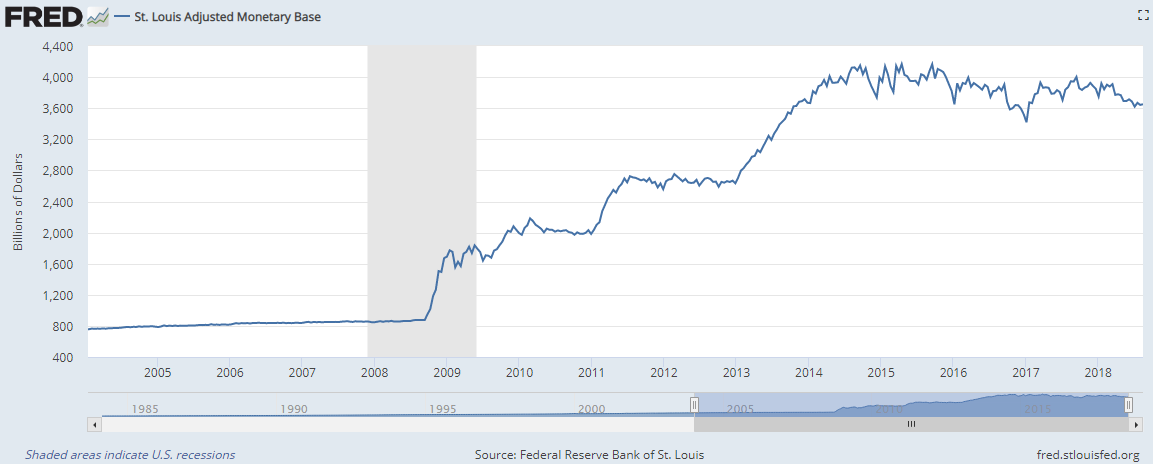

3. Third and finally, official inflation rates in the United States continue to hover at or below their target of 2%

Which is pretty good news for the people at the Fed, and they should feel good about managing the money supply, which has increased pretty smoothly over the same time period.

Now, that seemed strange to me at first because I remember reading a bunch from 2008 to 2013 about Quantitative Easing and how the Fed was “going to print a ton of money.”

And it seems like it’s true, they did “print a ton of money”:

But unlike the prophecies of talking cartoon bears, all this money didn’t drive inflation through the roof and crash the stock market. It doesn’t seem to have really gone…anywhere. It just hit the banks’ deposit reserves and sat there (right-hand graph above). Two trillion dollars, perhaps slowly winding its way down now, in excess of what banks are required by regulations to hold onto.

From all appearances, on every metric, any way you can slice the macroeconomic data, this whole process seems to have been managed…if not perfectly, at least as well as any person could have reasonably accomplished.

Champagne all round for the people who work there, and I really do mean that. No sarcasm, no cynicism.

The Problem

There’s just this one problem I can’t get away from, and it doesn’t seem to be anyone’s fault but my own.

The problem is that the full cost of continuing my education wipes out almost 5 years of my earnings, and is increasing from year-to-year faster than those earnings. It’s not that it’s expensive (although it is), it’s that the expense captures the whole balance of my savings. But maybe that’s okay, these things are supposed to be investments. I should be willing to trade savings now for higher earning potential in the future, right?

Well, yes. There’s something different between savings and earnings that I’ll get to later (spoiler: compounding). But beyond that, I can’t help but notice that after this little speedbump on the road to prosperity, bigger and scarier ones loom on the horizon.

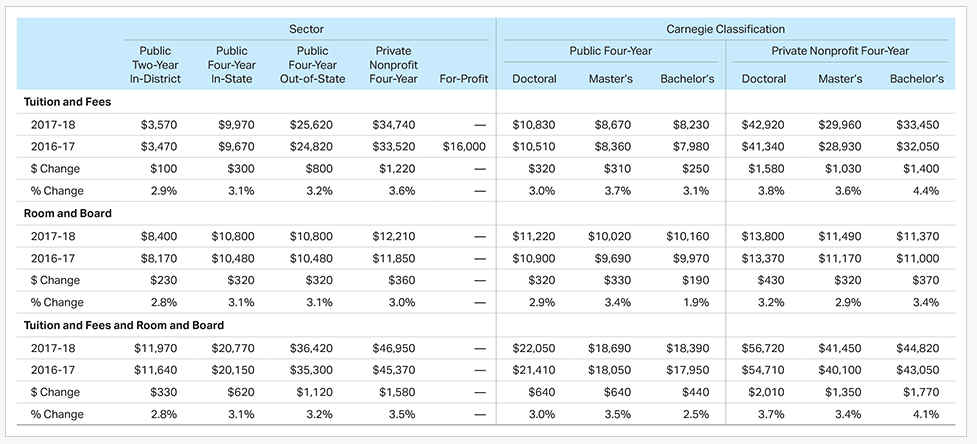

For example: if I want to fund an undergraduate education for my children (whose cost is designed to be borne by parents), we’re looking at $45,000 per year per child in 2018, growing at 4% per year.

If the growth in the cost of a Bachelor’s degree magically slows to 3% (is anyone in the whole world optimistic about that? I’m just trying to be conservative here…), it’s going to cost me $45,000 * (1.03 ^ 20) = $81,275 per child per year. Or $325,100 for all four years.

That’s an expense that won’t hit my budget at all for at least 20 years. And then in one four-year period $325,100 will come due. For my parents’ generation, a 4-year undergrad education cost them $3,100 — $6,200 per year, in real July 2018 dollars or $12,400 to $24,800 for all four years. ($2,500 — $5,000 in 2007 dollars per the most-recently-updated stats at that link, updated to July 2018 dollars using the official calculator)

This year we were reminded, as I think we’ve been reminded every year since 2008, that most Americans don’t have $1,000 in cash. I wonder how many American couples in their ~40s have $45,000 * 4 = $180,000 to spend on four years of their child's education?

Oh. That’s interesting.

Assets (Wealth) of married couples. 35-54. Kids probably about 18-ish: $142,425.

That’s damn convenient. The sticker price of college pre-loan or pre-financial-aid is about the same as the median net worth of married couples in America. Just enough to hit the reset button on those savings.

In that light, perhaps the cost of college for my parent’s generation ($20,000 for four years, per above), won’t look so outrageous if we compare it to the net worth of median Americans back then, which presumably was also lower?

Yeah, about that.

Now that’s not quite looking at the same age bracket as our married couple example, but the numbers make some sense. 538 wrote in 2014 that “the average american hasn’t gotten a raise in 15 years” — and note that if inflation was a constant 2% for 15 years, overall prices would have risen (1.02^15) = 35% over that same time period. If wages are flat and expenses are up, we might expect median net worth to be flat-to-down.

This is the problem. Not that the assets or wealth or wages are up or flat or down, but that the price of required-middle-class-purchases consumes all the wealth you can generate within one or two standard deviations of the mean.

Wealth Building

I’ve done a deeper dive on Education here, partly because a number of my friends have gone off or are going off to get their MBA recently, and partly because an Undergraduate degree has become an unavoidable prerequisite to entering the wealth-building middle class in America. Required. Wages might be stagnant in America, but if you don’t have a Bachelor’s degree, they aren’t stagnant, they’re declining. Good luck.

Because building wealth is what this is all about. You don’t want to be rich — rich comes and goes. You want to be wealthy, to be investing in more businesses, growing money not spending it. Wealth compounds, it builds on itself and it builds the future.

Most people don’t understand compound growth at all, and most humans have terrible intuitions about exponents and catastrophes. A dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow — because you can put it to work. People can understand that. What they can’t appreciate intuitively is the growth that comes when the additional dollar they earn gets put to work too. And the thing about compound growth, exponential growth, is that it often has a long-tail before meaningful returns are realized. You earn more money when you have more money you can put to work, and building that base takes time. See: the most valuable companies in the world (as of 2018)

So yes, a dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow. And $180,000 today, is worth a lot more than a dollar tomorrow. They don’t pay those wages exponentially.

The Devil’s Triangle

Here, then, is the Bermuda Triangle, wherein wealth vanishes. Illusory, magical, spiriting ships away, but at the end of the day it’s all babbling fake news and tabloid specials, right?

The southernmost point of the triangle is, and always must be, cost disease and stagnant wages. That’s the foundation of this whole phenomenon. Costs of some major products and services — of particular importance to the rising, aspirational, wage-earning middle-class — rise more than 1,000%, but nobody in the system seems to get paid more. Everyone outside the system also sees stagnant wages and declining wealth, the quality of the product barely improves, even declines in some cases, and we’re all left asking: “what the hell are we paying for?”

The westernmost point, closest to home, touching the Americas, is the personal point. The observation that the cost of relevant major products and services hasn’t just risen, it’s risen precisely to the level at which it consumes the entire snowball of wealth being built by the median-middle-class. You may request financial assistance, on bended knees, so long as you lay bare your bank account and declare the full value of your (meagre) assets. Kiss the ring — it’s the closest you’re gonna get to wealth for the next 10 years. College, health insurance, mortgage provider. You can’t hide wealth from their all-seeing eyes, their information is perfect and their price becomes simple.

The northernmost point, the strangest one, the namesake of this whole phenomenon, the magical act 3, is the fact that inflation has been at-or-below its target of 2% for 15 years and counting. Indisputably. The measure measures what it measures, and it measures it well, and it says 2%. Trillions of dollars of quantitative easing entered the banking system and didn’t rock the boat. Wikipedia confirms for us that: “In economics, inflation is a sustained increase in the price level of goods and services in an economy over a period of time.” And that is exactly what our CPI measures, and it says 2%, which means inflation isn't the driving force behind this problem.

And yet the very next sentence in that link says something that has a familiar ring to it for a certain (middle) class of Americans: “When the price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation reflects a reduction in the purchasing power per unit of money – a loss of real value in the medium of exchange and unit of account within the economy.”

How many years of education did $20,000 provide for my parents generation? How many did it provide for me? And how many for my children?

If you could convert the savings of the median-middle-class family into “effective-years-of-rent”, how many years did my grandparents have left after paying for my parents college? How many did my parents have left after paying for mine? How many will I have after spending $325,000 to send one child to college for four years?

The Bureau of Labor Statistics provides the relative weighting they give to each factor in the basket of goods that is the Consumer Price Index:

I’m not saying this weighting for College tuition is wrong — if the BLS says 1.613% (left-image), then that’s likely a very good estimate for what percent of all expenditures in the US went to College tuition. That’s what the measure measures.

I am saying that by focusing that 1.613% every year on the select group of Americans who have 18-22 year old children and who want their children to experience stagnant wages instead of declining wages, and who’ve been competing somewhat successfully in the labor market and building wealth, it is possible to wipe-out that snowballing wealth and delay their ability to invest and compound that wealth by decades compared to prior generations. All with just 1.613%. The result is that one four-year window reduces the purchasing power of Americans who want the best for their kids for up to a decade.

Every year. Applied to every cohort of middle class Americans as they pass through this Great Filter. The middle class’s expenses are not evenly distributed throughout their life.

$180,000 on a 4-year degree in 2018 would’ve been a $160,000 downpayment on a house for my parents generation, plus the $20,000 four year degree. Invested in the S&P500 for 10 years, $160,000 would’ve become $350,000. Or perhaps an investment in a new business. Or two $80,000 properties to develop.

Speaking of property, housing also experiences the same phenomenon. “Shelter” accounts for 32.720% of the weighting in the CPI calculation, per the table on the right above — and again, that’s certainly the right number for what Americans spend each year on rent and mortgages.

However, for the smaller segment of America that is making a first-time purchase, as opposed to making an annual lease payment, the segment that might be in the 30-50 year old bracket, the same segment that has to navigate the costs of their children’s education, whose cohort represents only a small fraction of the total population in any given year, they come face to face with a one-time expense that makes their savings disappear, magic trick, rabbit goes into the hat, no investing, no wealth-building for you.

Thanks, that’ll be $1,358,500, growing at 8-10% per year.

Of course, the CPI only includes actual expenses, not considered expenses, so if you think about buying a house but decide not to pull the trigger and blow your savings out, then you’re not going to show up in any stats. You’re invisible.

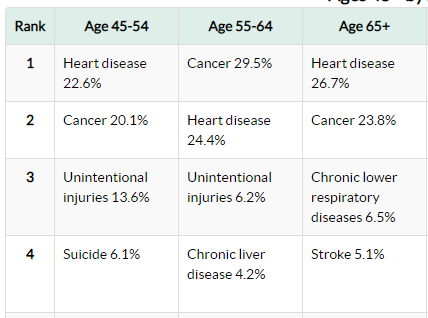

Come back after you’ve collected another 10 years of wages. Try not to have a heart attack in the meantime — I hear 50 can be a tough milestone to reach.

Spot the odd way out.

Up And To The Right

All these graphs with stagnant and declining lines are quite depressing — surely costs can’t be the only thing that’s grown faster than GDP?

But of course, not all of these purchases are made with cash outright, with equity, with wealth. Down payments fund mortgages, interest doesn’t even accumulate on college loans until graduation (how kind!), medical expenses can be deferred until after your life is saved and you’re back at work.

America is a place where you can defer payment today, attempt to build wealth and equity in the meantime, and make payments at a later date. Our system loves debt because it gives those with capital an avenue to invest in people with aspirations and drive, and people with aspiration and drive find they often need that capital to fund their (ever-more-expensive) ventures.

So we come, finally, to debt in America.

Consumer Credit Outstanding up 50% from its 2008 high — GDP up 17% over same period

Outstanding Mortgage Debt recently surpassed its 2008 high…

Student Debt up 132% since Q2 2008, now $1.5 Trillion…can you spot the recession?

Whence the Debt?

And to bring this full-circle, I am reminded that Debt does not come from the ether. Someone must “buy” the Debt, someone has to give you the loan.

If nobody was there to take the other side then the whole show might grind to a halt, and we almost had that happen in 2008 and nobody wants to go there again.

This time, though, the loans aren’t “bad”. SUBPRIME echoes in the mind of everyone who listened to the news any time from 2008 to 2013, but don’t bother fighting the last fight. We’ve learned since then (probably). The euphoria, the crazy loans, the risk taking, it’s all been tightened up a bit (I’m told). Dodd-Frank might’ve done something, although I hear some of it has been repealed now. I’d like to have an opinion or at least a hot-take, but it’s 2,300 pages to read the original version and ain’t nobody got time for that. Especially not members of congress. That’s pre-2008 thinking anyway. The Old World.

In our New World lenders only ask for EVERYTHING from those who can spend 10 years earning it back. Nothing subprime about it. And they look under the skirt at all the checking accounts, just to be sure.

Pictured: definitely not the end-state of the game.

And just in case things do go tits-up, the banks still have $1.8 Trillion on their books in excess of what they are required to keep by law. Just in case.

Sometimes, in my chocolate-and-tea-fueled conspiratorial moments, I wonder who really controls our monetary policy now, the Fed or the private banks, given that such a huge cash balance sitting in excess reserves likely makes private banks somewhat impervious to rate-changes. Thankfully, much smarter people than me already thought of this and the New York Times helpfully explained earlier this year how the Fed changed its method of control:

Before the crisis, the Fed raised rates by selling bonds to reduce the availability of reserves, which banks are required to hold in proportion to their holdings of customer deposits. But banks now hold plenty of excess reserves. Rather than reversing its bond purchases completely to drain those reserves, the Fed instead decided to raise rates by paying banks to leave reserves untouched.

The Ben Bernanke himself helpfully explains this New System for a New World in a short essay of his here, if you like reading about macroeconomic policy but missed the memo.

For What, the Debt?

Why does any of this impact the middle class? Because it’s important to know where the debt is coming from in order to evaluate what it’s being spent on. Per Big Ben’s essay, banks don’t have to be desperate and reckless and wasteful with their deposits anymore — the Fed has them covered to some baseline.

Which means all this debt piling up faster than GDP in the charts up above — that isn’t some bubble waiting to pop. That isn’t desperate money chasing reckless profits — that’s the last battle. This debt has been calculated, the loans have been weighed, and something obvious has been rediscovered: the productive class in America can bear more. A lot more.

If you think this magical ride plateaus at the rational maximum value of an education (or a home or medical care), you’ll enjoy learning about Dollar Auctions.

The New York Times also reported this week that “The Student Debt Problem Is Worse Than We Imagined”, explaining that default rates have risen — particularly at some unnamed “private-for-profit” institutions, which is of course true and bad and also misses the point. Because what they can’t show you is Default-Rate-by-College and Default-Rate-by-Major.

1,845 private 4-year institutions in the US? Can anyone name 200?

Here are the US News and World University Rankings and College Rankings lists, which are based on a mix of hard data and tea leaves, much like my own writing. Ignore the dispute for a moment about whether your college is #1 or #10 or #30 or #50 and you might notice that the actual rankings themselves stop at #223 and #168, respectively for universities and colleges. The rest apparently don't merit a ranking, even in our society driven by putting numbers on things.

Wayne State University ranks in at #223, losing the seven-way-tie for Worst Ranked University in North America thanks to the Alphabet. In-state tuition is apparently $13,278 (plus all the other costs associated with being a student, housing, food, books, etc). The average salary for graduates with <5 years of experience is $48,800, rising to $88,300 for graduates with 10+ years of experience.

And this is the WORST university we give a ranking to? A $309,000 estimated return on investment, not-adjusted-for-major. You have to visit Payscale, click “See Full List”, and scroll past 1,752 colleges before you find one that doesn’t have a positive RoI — not-adjusted-for-major.

The Kids might not be All Right, and it might take them much longer than their parents to build any wealth, but the Debt is going to be just fine.

What’s the Solution?

To the cost disease? To the removal and delaying of wealth from middle class Americans at every major step of the ladder? To the systemic problem? To inflation of 2% for both the rich and the poor, and something-that-isn’t-inflation-but-massively-wipes-out-wealth-and-lowers-purchasing-power for the middle class?

I don’t bloody know.

But the solution on a personal level, for you, for me, is crystal fucking clear.

Preferably without dying. But wealth compounds, so the risk is worth putting some stress on your body. “According to the American Psychological Association, chronic stress is linked to the six leading causes of death...”

Thus Moloch. Thus War: “won by those who sacrifice everything to achieve victory.” Shout out to Kratos for that one. Thus the price of a college education will rise further, as we all sacrifice current savings and future income to take the next step on the ladder and hopefully begin compounding wealth before our peers.

I paid off my loans in just two years, which means the college and the bank missed out on earnings and my MIT degree was underpriced by 3-8 years of expected earnings (pre-tax, because you can pay these debts pre-tax unless you make over $80,000 a year...oh, right).

So long as the debt is there to fund it, or the surplus wages there to support it, the show will go on. This is the struggle of the middle class in America today. It’s not the only struggle in the country, nor even close to the worst one. There’s nobody behind it, no grim cabal to blame. But it is a struggle, and one that seems to evade stats and articulation and empathy and sympathy and an escape. The only enemy is your failure to beat the median quickly enough and by enough standard deviations.

Success only begins when you build enough wealth to pay for:

Your own continuing education: $0 — $125,000

A home for your family: $750,000 — $1,500,000 (depending on how far you are willing to move from a major urban center — but don’t move too far because the wages go down too)

Education for your children: $180,000 — $325,000 (start at the bottom of the range if your kids are 18 today, move up accordingly)

Medical expenses: $50,000 guaranteed between childbirth and insurance, more with pre-existing conditions or any large event

Your own medical care as you age: $0 — $LOTS

Adding all those up, the bottom of that range is $980,000 in cash for one-time expenses and it tops out at $2,000,000.

Just to get to back to $0 balance.

Competitive Spirit

Of course, you can perform standard-deviations above the mean, fulfilling 50 Cent’s dream, dragging the mean-or-median wealth ever so slightly upwards along with you, and thereby raising costs for everyone else who couldn’t make it. One standard deviation and you get Avocado toast in your twenties. Two standard deviations and you get a nice car. How many for a home before thirty? You’d have to be The Six Sigma Man, as The Six Million Dollar Man becomes The Six Billion Dollar Man because we all know $6,000,000 isn't enough to build a superhero anymore.

Or you could perform standard-deviations below the mean, be left behind in a world where there is slim hope of real wealth, aspirations are more about next month than next decade, but at least inflation for everything you care about will be about 2% every year. And, once more, you’ll be raising costs of any major services (Education, Housing, Medical) you do use for your peers at the median because someone has to pay.

The result is that the solution on a personal level, “Get Rich or Die Tryin’”, raises the bar for everyone else no matter the outcome, and is a driving force behind the systemic problem of personal wealth-building that it is trying to solve. And America’s middle class has been an absolute workhorse, and it has beaten the median, and it has raised the bar higher and faster than almost any other nation has ever raised it in history.

That’s not a coincidence. The promise, the deal, was almost unheard of: “work hard, work smart, create value for society, and you’ll become wealthy, your own master for all eternity.” The slave works for his owner. The indentured servant for his master. The communist for everyone. The American for himself. It’s a powerful idea, a powerful motivator, and a powerful system. A grand competition, where advancement can be achieved through merit and competence — so don’t be shocked when those with merit and competence flock to compete. And they make perfect competitors.

For those who have forgotten their first Economics lecture:

Perfect Competition: “In a perfect market the sellers operate at zero economic surplus…This equilibrium will be a Pareto optimum, meaning that nobody can be made better off by exchange without making someone else worse off.”

Oh. Right. That sounds fun. What does that look like, again?

I’m not saying we’re there. Middle class people still get to build wealth — economic surplus — when they sell their labor in America if they can beat the median a little. College still has a positive RoI. The median American can own a house and pay off the mortgage and still have savings left to spend on end-of-life-medical-care if they’re willing to move suitably far from centers of employment. This isn’t Perfect Competition. But if you squint hard enough, you can see it from here.

That’s the race and the clock is ticking for you and your great-great-grandchildren. The starting pistol fired in 1776.

Disregard Emails, Acquire Currency

Wealth compounds, but wages don’t grow exponentially. You’ve got to start that compounding yourself, the sooner the better — which is why we taught everyone in school how important this was and how to balance their budget. Or at least why we taught them that getting into college was the most important thing in their life, anyway. Those are about the same, right?

Want to hear a joke?

Knock, knock.

— Who’s there?

The taxman. I’d like 30% please. 40% if you got a bonus this year. Good job.

— You realize I’m still paying you back those student loans, yeah?

We tax income, not assets and liabilities, and anyway you can pay your debts to me pre-tax unless you made one-standard-deviation-above-median income this year

— But if you let me compound wealth I’ll be able to pay the loans back faster!

We’re not interested in that

Here’s another:

Knock, knock.

— Who’s there?

A recession. Your wealth is reset to zero.

— But I have to pay for the kids college this year…

Don’t worry, I looked under your skirt and saw you earned a healthy income from wages last year, so I’m sure you can afford it. Besides, last year you said your house was worth a million dollars!

Or an old classic:

Knock, knock.

— Who’s there?

Medical conditions! Your income means you have to pay out of pocket

— But doesn’t my one-standard-deviation-above-median income mean I’ve paid more in premiums to cover it?

What premiums? Oh. We’ve reset those too. You should’ve said you had conditions!

Of course, all these costs can only scale so far. The middle class must be able to fund them — and since wealth in America is distributed exponentially, what’s all-consuming for the middle class is peanuts to the wealthy. So Wealthy begins with a race to $2,000,000, adjusted-annually-to-the-cost-of-education-housing-and-medical-expenses.

See you guys at the finish line.