How Elites Cause Crime By Acing Marshmallow Tests

Some people think crime is caused by poverty. Some think crime is caused by criminals. Some even think crime is caused by the climate. Don’t swallow these easy-to-digest popular narratives — society is shaped by its elite, always has been, always will be. It all comes back to the marshmallows.

A brief summary of what’s to come in this essay:

Online science analyst Crémieux wrote a provocative piece recently exploring why poverty alone is insufficient to explain variation in crime rates and showing how the Venetian upper class was massively overrepresented in violent crime until warfare reduced their numbers to near-zero. But as a firm believer in the idea that everything is downstream of economics, I want to present an alternate causal hypothesis that inverts the usual narrative: poverty doesn’t cause societal violence — how you become an elite does.

The selection process of each city’s elite members differs according to that city’s dominant economic industry. I suggest that the eventual downstream consequence of selection effects introduced by those different industries causes much of the variation we see in crime rates across space and time.

This essay doesn’t aim to provide a comprehensive and total explanation for differing rates of crime among cities — but it does attempt to provide a novel perspective based on economics, psychology, and culture. To begin, I must start with what it means to become an elite…

(this is funny & deeply ironic & proof that modes of economic production have profound impacts on culture, but don’t forget the Taliban are still bad guys here)

Elite Formation: Passing Tests, Jumping Through Hoops

You can read about why college matters more than ever despite costing ~everything your family can afford to give, and then you can read about why it “shouldn’t” cost so much from people who nonetheless attended prestigious institutions and try as hard as they can to get their kids into good schools.

Universities today find themselves at the center of a political storm, but any attempt to retreat to “mere academics” will fail — they have become the first step along the path to “elite” status in our society, not just for a tiny handful of patrician families, but for the vast bulk of the aspiring American middle class.

After graduation, aspirants must progress through the ranks of institutional credibility in their chosen arena. Harvard Medical School. Goldman Sachs. Google. The New York Times. Wherever it is they go in D.C. and LA.

A graphical analogy:

The course of honors — Cursus Honorum — in Ancient Rome during Caesar’s time. The ancient version of elite social climbing. You can feel free to tag yourself.[0]

There exists a modern day Course of Honors in all domains. While most citizens need to climb each rung on the ladder, sufficiently talented or well-connected folks can often speedrun the course. Much of the Venture Capital ecosystem exists to try and enable such speedrunning.

And it is through this course that ambitious youngsters are funneled each year, with the cream skimmed off into an ever-more-selective echelon at each stage. That Roman diagram has ~300 slots available at the bottom for Military Tribunes! The shortlist gets culled to only 20 per year on the very next rung on the ladder!

30 Under 30, Res publica Romana edition.

Our own version of this course of honors has more variety to it — after all, there’re more ways to become wealthy in our society than ancient Rome’s. For most domains, particularly those coded as suitable for the ranks of the modern Equestrians, the first step of college at age 18 means intense academic study during childhood.

Which brings us to my favorite essayist, hotelconcierge, and his wonderful thesis that in attempting to select our modern elites purely through meritocratic academic competition, we inadvertently also select heavily for the psychology profile that drives a teenager to study 8 hours a day throughout childhood: “The Desire To Pass Tests” (TDTPT).

this whole quote is phenomenal…”it’s really not about candy” indeed source

His essay covers everything from IQ testing to Med School admissions to anorexia and the gradual descent into competition-induced-dystopia and psychological disorder.

And his key observation is that this Desire — the raw need to “please authority figures” — is heavily selected for in our modern elites.

Once you understand that additional study improves test scores and outcomes, everything else slots into place. Between two smart-enough kids, which one gets into college?? The one who pushed themselves harder to read dull textbooks despite hormones, social media, videogames, and marijuana all vying for attention.

And who pushes themselves hardest of all?

The “maladaptive perfectionist” of course — whose gut churned with anxiety and self-loathing when they received that 95% and fell far short of their expectations.

The more insane someone’s expectations about their own performance, the more they push themselves. The ones who overachieve the most are those who devise the most effective ways to manipulate their own psychology into jumping through ever more inane hoops, no matter the test that’s put in front of them.

His follow-on point is that these people are all deeply unhappy.

Thus: at scale, on the societal level, selecting for academic performance also selects for unhappiness.

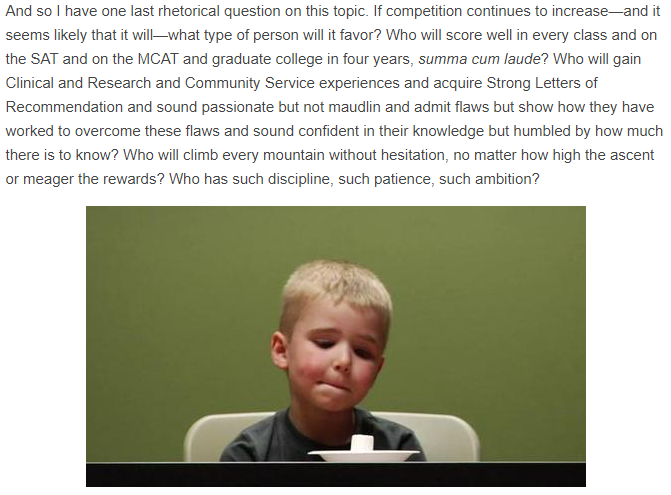

And so our society’s gloriously selected elite are all shades of this young boy:

Pictured: the modern Caesar. If you haven’t seen this footage, I highly recommend taking the 3mins to watch it.

This young boy is the only one who makes it through the test without eating the marshmallow.

The only one.

Every other child fails.

Watch his face contort as he tries to force himself to pass the test. Watch him hold his face in his little hands and avert his eyes from the pathetic prize.

Watch as he finally grabs his reward at 3:08, and even after passing the test, looks back and makes hard eye contact with the test administrator, waiting for her additional approval, and only finally smiling when she reassures him that he can, in fact, eat the marshmallows she has already given him and already told him are his.

You don’t have to be a psychiatrist to find the whole thing tragic.

You don’t have to be a parent to wonder if this is what success ought to look like.

And you don’t have to be an elite to know this type of child.

If you have ever made it through a single selection stage in the modern day Course of Honors, you’ve met this boy a hundred times over. Perhaps he is you. Hotelconcierge has it almost exactly right — the selection process selects for a certain psychology as strongly as it selects for anything else.

I say “almost” because I think this phenomenon actually has two-layers to it, and the gap between these layers will connect back to the messy topic in this essay’s title.

The first layer is covered fully in hotelconcierge’s essay: The Desire To Pass Tests.

The second layer is its complement: The Ability To Pass Tests.

The Limits of Desire

Hotelconcierge sidesteps the awkward discussion of differential ability between students by pointing out (correctly) that he was able to improve his own scores on various tests simply by studying, and that he enjoys this process and has a high innate Desire To Pass Tests.

Studying works.

And yet.

Whatever the backstory may be, the reality is that no two people taken from any single stage of the Course of Honors will have the exact same ability to pass the next test on the rung at that precise moment in time. One child may need to study for 6 hours to achieve an A+, while another may need to study for 18 hours.

Advancing to the next stage requires passing the test. So yes, the high Desire To Pass Tests individuals will get their neuroses ramped up, contort themselves like the boy in the video above, and get to work on practicing.

Many will advance.

Pictured: a high Desire To Pass Tests [editor’s note: pictured is a children’s cartoon character who has no special abilities but works 1,000x harder than everyone else — i will not spoil the ending of his character arc for you]

But my retort to the dystopian conclusion of hotelconcierge’s essay, which ends with a grim future of relentless rat race competition over a handful of jobs under the emotionless administration of an AI fueled by zero-cost energy…

…my retort is that some of the people who ascend the Course of Honors do in fact possess extraordinary ability. Some of them only needed to study for 30 minutes. Crucially, the distribution of kids at each rung on the Course of Honors depends on the selection criteria to get there. Whether you get a 9:1 ratio in favor of Desire To Pass Tests vs. Ability To Pass Tests or the total inverse ratio depends on how you’re choosing who advances.

If you were looking to build a healthy psyche for yourself or your children, it’s important to focus on building a balance between The Ability To Pass Tests and The Desire To Pass Tests.[1]

now I’m not saying you should lock a powerful spirit within your child’s belly, of course — merely give them as big a leg up as you can [editor’s note: the above is also a children’s cartoon character who receives various natural & unnatural gifts from his parents — and despite inspiring much resentment from others due to these gifts, he ultimately achieves his goals and life satisfaction]

How do we get from here to violence?

From passing tests to navigating conflict?

It’s all contained in the final few frames of the test:

at this point in time the boy has already been told the extra marshmallow is his…and yet.

Hotelconcierge wrote about the intense unhappiness of these kids. Given his own medical background, that makes perfect sense.

But it’s not their unhappiness that catches my eye. It’s the lack of agency.

Or rather: the boy does achieve agency — a sort of meta-tier-2-agency — by overcoming his own desires in deference to the preferences of an external authority figure. He doesn’t do what he wants, he’s better than that. He does what you want, despite what he wants. He’s better than you, but he’s jealous of you. He wants to eat the marshmallow, but the thought of doing so causes him moral disgust. Sometimes he wishes he could be like you, happy, sated, laughing about it, but no part of him actually wants to be you. He is able to control himself. He is unable to act on his own desires. He is destined to succeed — because he was told to. It will never be enough.

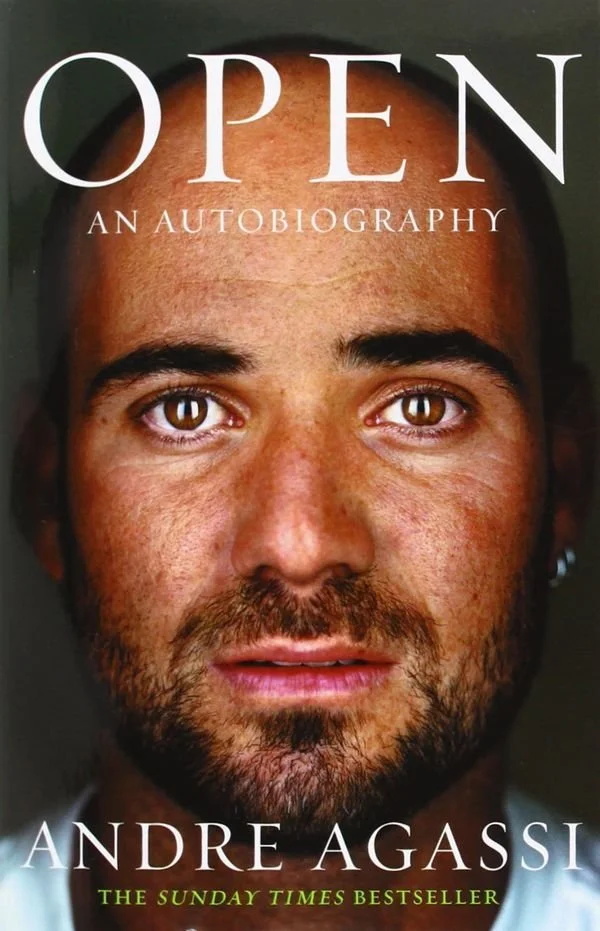

I don’t know, read the book if you still have questions:

not only is this psychology not unique to academia, I find the athlete’s perspective on it is often more “open” and approachable to an audience who wasn’t prepared to find it outside academia — most readers never imagine themselves to have a shot at being a pro athlete and so are more easily able to slip into his worldview, like reading a good fiction book

Selecting an academic and professional elite whose dominating emotional urge is compliance, even when it conflicts with personal interest, has massive follow-on effects for the shape of society that elite tries to create.

The external authority — the one who passes judgment, A+ or A-, internship or no internship, swipe right or swipe left, worthy or not, college admit or not — must be satisfied before the boy allows himself his meagre reward.

Do not judge that little boy for doing what he must to pass our tests.

Statistically speaking, he and those like him are responsible for every part of the world around you.

Your Responsibility: Non-Compliance & Disregard for Authority

What happens when The Boy Who Passed The Test meets The Man Who Didn’t Care?

How does the boy who aces a marshmallow test view his peers who did not?

When he grows up, how does he interact with people who don’t hesitate to eat the marshmallow?

Consider this celebrity YouTube video, which begins with Lil Wayne mocking a lawyer for his bad questions and climaxes with him telling that same lawyer, on camera, in front of a judge, “you know he can’t save you, right? in the real world?”

“I was talking to myself”

Lil Wayne obviously has no respect for the proceedings, and therefore the system that those proceedings represent, and calls attention to that directly with his threat of consequences “in the real world.”

The Judge does not chastise Wayne or sanction him for cutting the lawyer off.

The attorney asking him questions is audibly unsettled and starts trying to re-assert authority by forcing Wayne to comply with increasingly inane and obvious questions.

But Wayne is not interested in compliance and the whole thing escalates into comedy.

This clip was introduced to me in an essay by another psychiatrist, and his discussion of the psychology of violence across class lines remains true over a decade later:

Wayne may be the aggressor but the voice inside asks, "what did you do to provoke him? Why didn't you stay away from him?" This fear is so primary that the lawyer backs down from Wayne for Wayne's sake, not to avoid getting hit but so Wayne doesn't have to hit him. Wayne is feared not because he's good at winning fights but because he's good at starting fights, and its oddly been indoctrinated in us that it is everyone else's job not to provoke fights with those you know will fight, even if you're in the right.

I want to point out how this dichotomy is very much predicated on a difference between people, not a sameness, and it's felt to be part of the hardware, not the software. There's you, who "knows better", and there's him, who "fights", and that's just the way it is. And since you "know better" it's your responsibility to not let this get out of hand. Pro-gun proponents can be seen as the logical consequence of this position: ok, I'll accept your societal commandment not to fight, but I want to preserve my right not to have to back down, either. The sad, logical retort to this comes from a place of compassion, though, when I write this out explicitly, is really just a kind of kind of classism: "it's best just to back down from them... because that's they way thems are."

To engage in violence — even to be engaged-upon by another in violence — is perceived as failing a societal-level marshmallow test.

As with all other marshmallow tests, your ability to ace them is used as a class indicator and an IQ check.

“What, are you [stupid] or something? You should’ve known better!”

The boy who stares at the marshmallow without reaching for it, who contorts his psyche for a decade straight before he sits for a college entrance exam, can feel only two things towards those poor unfortunates who couldn’t do any better: pity and derision.

And my real point is that the aversion to violence itself — and the author of this second essay thinks it’s taught, whereas I‘m saying yes, it is, but being able to be taught this stuff in the first place simply correlates with The Desire To Pass Tests — can be incepted into any child with a high desire to comply.

Even though Lil Wayne is the celebrity face of this little clip, it’s the behavior of the Judge and the Attorney that matter: they have ascended high up their respective Course of Honors. They achieved. They jumped through hoops. They are probably masters of manipulating bureaucratic procedures to achieve their goals.

But the Judge would rather not have a physical fight in his deposition room, just as the teacher wishes to avoid one in class. The attorney views pleasing the Judge as a Test to pass, as I’m sure he once viewed pleasing a teacher as one. And from there it’s a short leap to the attorney viewing Wayne’s behavior and potential “real world” violence as his responsibility to manage.

Pictured: a high Desire To Pass Tests

How does any of this relate to violence in society and elites?

The clip shows a man being allowed to threaten a ranking Equestrian member of society, on camera, during a deposition, in front of a Judge, without consequence.

In the modern world an overriding Desire To Pass Tests eventually leads to an aversion to all forms of violence, including violence used in response to threats, and a belief that oneself is directly responsible not just for the violence one does to others, but also the violence they force others to do to them.

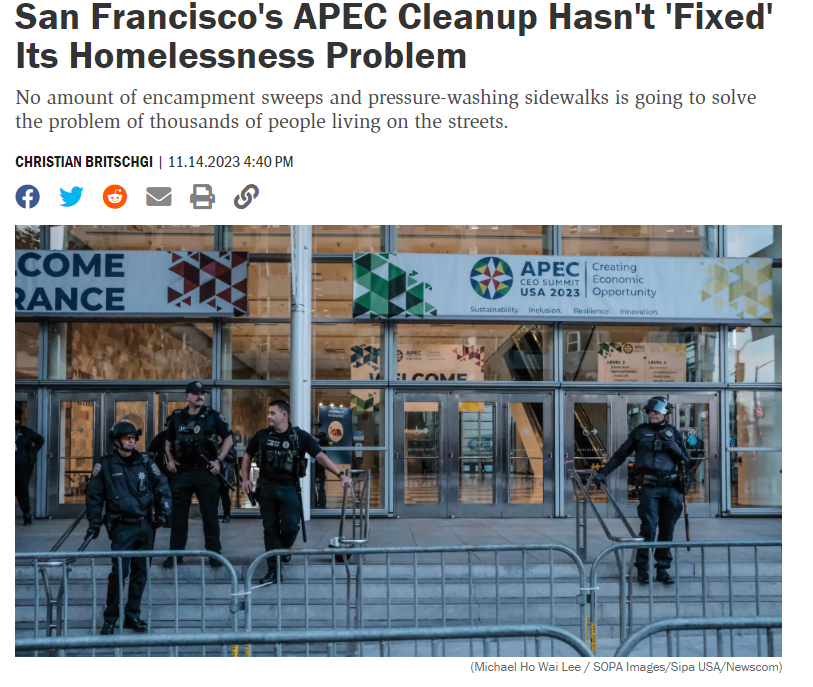

You may think it’s just a dumb clip about a celebrity bullying some dopey lawyer, and it is that, but it ultimately has deep ramifications for the rate of property crime in San Francisco.

Who is responsible for the table below?

2019 reported figures show San Francisco with the 4th highest rate of property crimes in the US (on the right in table above)

Anecdata: A Tale of Two Marshmallows

There are two cities within San Francisco’s crime data.

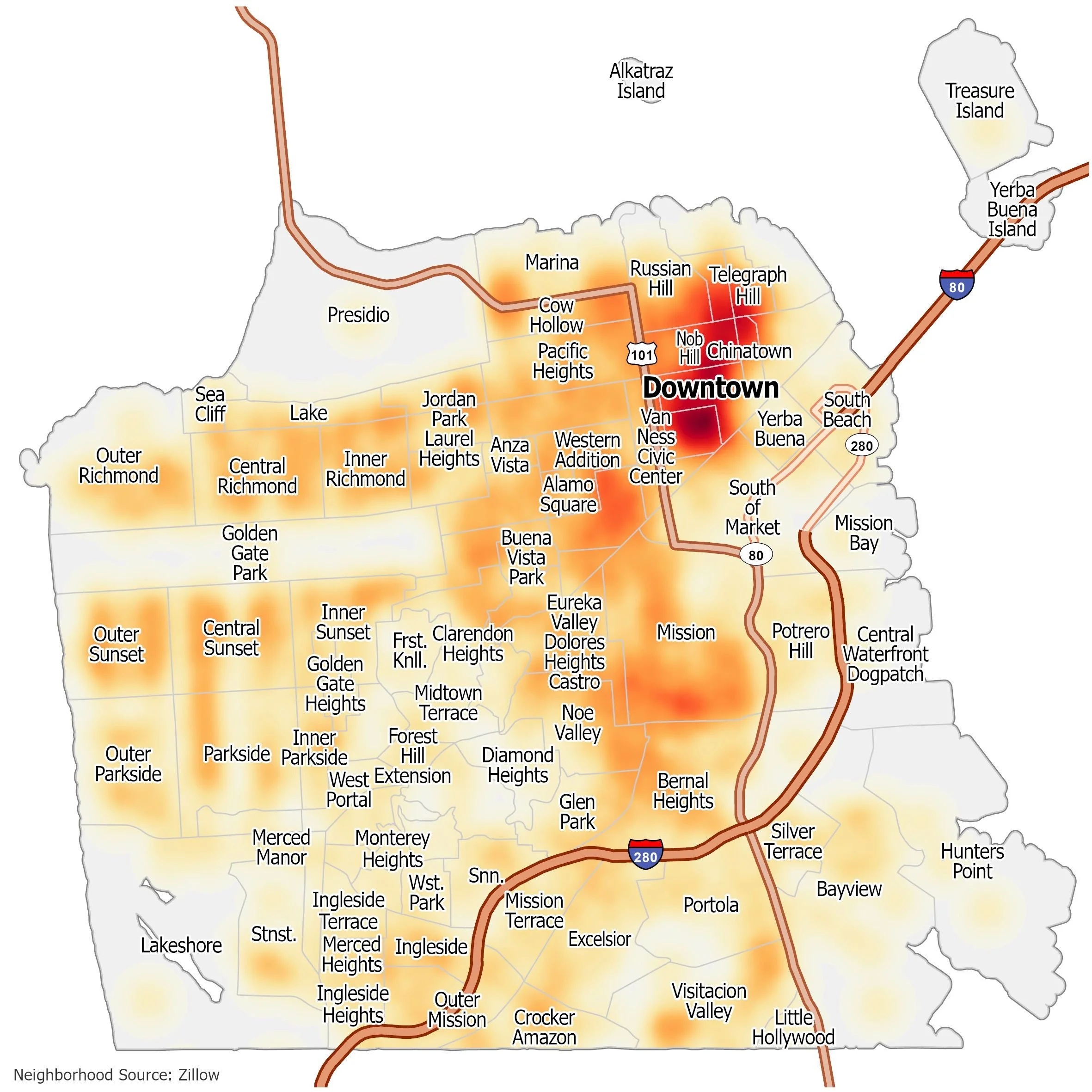

crime map (source)

When it comes to murder, rape, and aggravated assault, San Francisco is the 35th safest city in America. 35th is far from perfect — you’re 2-3x more likely to be murdered in SF than San Diego, twice as likely to be raped as you are in Sacramento, 13x more likely to be aggravatedly assaulted in SF than in Irvine. If you care about avoiding these things for your family, these ratios are not entirely irrelevant.

However. There are 165 cities in America where you can be victimized on these 3 dimensions more often than in San Francisco. Whether you view this as an endorsement of San Francisco or an indictment of America is up to you and beyond the scope of this essay. Either way, it cannot be said that San Francisco is aberrant from the national norm on violent crime!

When it comes to grand theft auto, robbery, burglary, and theft, another San Francisco emerges.

For motor vehicle theft, SF is only the 67th safest in the nation, and you’re 8x more likely to get your car stolen in SF than in New York. For robbery, we slide down to 81st, where getting violently robbed is 9x likelier in SF than Scottsdale. Alas, it gets worse. Theft — losing your property with slightly less explicit violence — sees San Francisco ranked as the 199th safety city in America. Out of 200. You’re going to get your stuff stolen 4.5x more often in San Francisco than Newark. [note for non-US readers: Newark is renowned for being generally unpleasant on the crime front]

Some have suggested that these numbers may be underreported. They probably are. But I think the divide is stark enough that you can take them at face value and still understand my point.

Here’s a list of cities I’ve considered living in or had friends ask me if I’d ever move there, ranked from highest to lowest crime rates. Look at the highlighted column:

Sorted by property crime rates, top to bottom

While young, healthy, relatively fit, well compensated tech workers may perhaps look at data like this and go "eh, I'm not that likely to be murdered in SF and property crime won't really affect me", and I agree that this may be reasonable from their point of view, it’s nonetheless a specific view of safety, violence, and crime that is not universal — and one that would not find a home in many other American cities across both time & space.

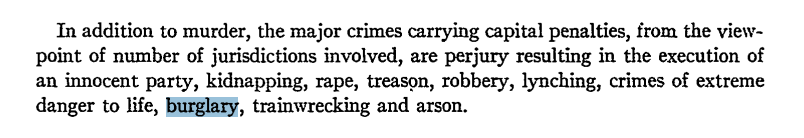

source: 1955 PhD thesis on the various types of crimes that earned the death penalty across different states in the US — burglary was tied with lynching. Which is not to endorse that position, merely to highlight that the taking of property was viewed as a capital crime in 15% of american states during your grandparents’ era.

But regardless of how you feel personally about property crime, the degree to which San Francisco sticks out on property crime is impressive.

While there are many factors that influence these numbers, it’s the reaction of the elite that most interests me.

In answer to the question: when is it acceptable to endorse state violence to suppress property crime?

San Francisco has answered clearly:

Surely you’re smart enough to follow this simple instruction, right?

We told you not to eat the marshmallow.

If anything bad happens to you at this point, well, you should’ve known better.

Venice Can Be Venice Only Because Others Are Not

Tab back to Venice for a moment and Crémieux’s observation that its elites were overrepresented in assaulting other citizens.

Today there are fewer nobles spilling blood in the streets of Venice

The idea that the sort of policing a city chooses influences the level of crime in that city is hardly unique, and law & order diehards often like to pretend nothing else matters and nothing else is worth trying. That’s not what this essay is about.

What I’m trying to get at is that the preferences of a city’s elite are entirely responsible for shaping its [societal] response — and those elites will be selected via economics in different ways based on the dominant industry of each city.

The political philosophy of a city depends on the way the city provides for itself economically.

In a way, I’m giving a pretty fatalistic analysis here: you shouldn’t expect to be able to change things without also fundamentally altering the Big Tech economy.

Looking back to Crémieux’s essay, Venice can be Venice only because its nobles are violent people. The glory of a “maritime trading empire” has always been built first and foremost on conquering the seas.

A state economy built on the backs of capable seafaring merchants necessitates selecting elites for their ability to engage in self-motivated, self-directed, self-rewarding violence, covered only by the thin veneer of mutual allegiance to the Republic. A ship at sea in the 1400s has no police to call, no Pax Americana to save it. Slavers, pirates, and actively hostile conquering empires are all sailing the same seas.

The price of Venice’s beauty is gold, and the price of its gold is blood.

Truth be told, I had no idea about this side of Venetian history before going to look for a nice quote from Wikipedia, but my mental model of what it means to build a maritime trade empire told me it simply must be so. If my description above also pattern matches to my writing on the unavoidable geopolitical violence of Mercantilism, well. It should. One small hope of my writing is for more people to understand the value of "[regional] hegemony” in order to achieve “dominance of trade routes.”

Of course, Venice is not unique.

This is not what most people think of when they hear “Venice” today. And yet it was the necessary precondition to what came next.

Thus could Venice’s Wealth only be achieved through the willingness of its “best” citizens to lean into violence. That they brought those same attitudes home after work is hardly surprising.

In much the same way, San Francisco can be San Francisco only because its nobles have an abnormally high Desire To Pass Tests.

“Big Tech” was coined only in 2013 — consider what that means for the changing landscape of the city’s politics and the relative ascendency of certain values. The wild west of Startup Landia has been on the downswing for a decade and the rising superstar had to have a perfect resume. Because no real resume would be good enough.

Yes, this movie did also come out in 2013, what a coincidence. No, it’s not good. Watch the trailer if you’d like to relive the message: “your company is closed…you’re dinosaurs…this is the last chance you’ve got…5% of you will be offered a fulltime position, the other 95% will not…”

Consider what it takes to navigate the cross-functional organizational bureaucracies of mega-monopolies who sell product into every geography & every culture on earth, while also retaining domain expertise within your own branch of the company and scoring highly on 360 performance reviews. Consider the number of hoops you must be able to jump through to climb the ladder that environment when your competition for the next rung in the Course of Honors is every kid in the world who aced a marshmallow test. It’s no wonder we select for compliance and cross-functional collaboration and the ability to sublimate personal desire — the tech economy would go splat if we did it any other way.

To rephrase hotelconcierge: “Who will score well in every class and on the SAT and on the GMAT and graduate college in three years, summa cum laude? Who will gain leadership experience and acquire conference speaker accolades and sound passionate but not naïve and admit weaknesses but show how they have worked to overcome these weaknesses and sound confident in their knowledge but humbled by the talents of those they’ve worked with? Who will be able to inspire their colleagues without offending any of them, deliver negative feedback while highlighting potential growth areas in motivational ways, and successfully manage the egos of reports, teammates, and managers who all have perfect resumes and imposter syndrome?”

Who indeed.

And so, as with Venice:

A state economy built on the backs of centralized Big Tech global monopolies, funded by an agglomeration of global capital, necessitates selecting elites for their Desire To Pass Tests, above and beyond all else — which thus means also selecting for more unhappiness, more anxiety, more imposter syndrome, and the belief that violence of any sort, even victimization, is a personal failing.

As in Venice, so in San Francisco

[editor’s note: as a fellow acer of marshmallow tests, I of course support this system and mean only to present my analysis of it here and not to suggest something else is preferable]

A Theory Of Violence: Escalation Theory

So far in this essay I’ve talked about two kinds of people who commit violence: American criminals and Venetian nobles. One personal belief of mine is that people outside these groups have very poor theories of mind for how they operate. So I’d like to take a moment to explore how someone who is unphased by the thought of interpersonal and intersocietal violence approaches conflict and conflict resolution.

Pictured: a movie popular with people who like the idea of responding to threats by escalating the level of violence occurring

The mindset of someone with high system-level compliance — high Desire To Pass Tests — is to avoid, de-escalate, and otherwise mitigate any potential altercations, because system administrators always prefer peace to violence and their preferences become your preferences by the time you graduate middle school .

Conversely, the mindset of someone without this high Desire To Pass Tests is to map out the value of potential escalations and opt-in or out based on maximizing personal outcomes (or, more often, based an intuitive guess of potential outcomes).

Escalation Theory comes naturally to people with prior exposure to conflict. Escalation Theory is built on the understanding that all conflict, no matter how small, has the potential to escalate into existential conflict.

That is: all conflict is violence and all violence is probabilistically terminal.

For these people, the potential Escalation acts both as a restraint in the moment and a catalyst in the moment-to-come. You’re hesitant to over-escalate, lest you trigger an exaggerated response too swiftly and get yourself hurt. But you’re prepared for the other side’s escalation, even planning it in your mind, and ready to react quickly if they do opt-in to the escalation.

“Gradually and then suddenly.”

You are never shocked, never surprised, only waiting taut for a response or actively responding with an escalation of your own.

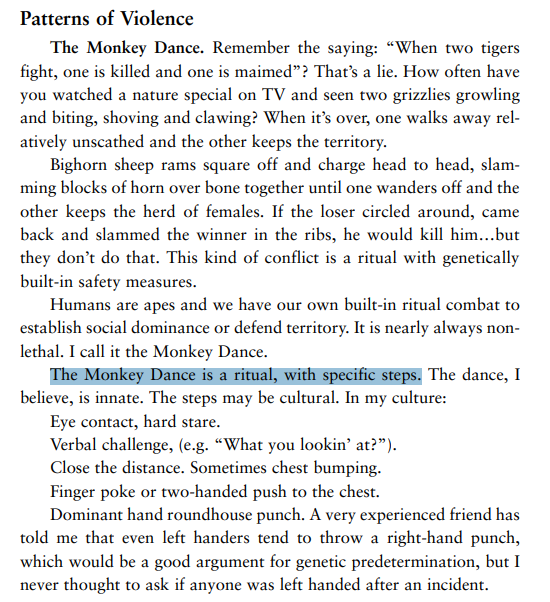

Before any of that can unfold, participants in the dance are presented with an escalating question: “will you challenge me?”

Navigating this escalating back and forth, asking the same question to each other in turn, passing it back and forth like a hot potato, is completely alien to someone who has only lived within systems designed by and for people with high Desire To Pass Tests.

Sgt. Rory Miller writes that the Monkey Dance as he understands it is nearly always non-lethal, and that’s true in the sense that most dances don’t end in serious injury. But the inverse is not true: a great many serious injuries did in fact begin with a Monkey Dance. [editor’s note: on balance I’m opting not to link the thousands of clips of such dances you can find on YouTube because I think it unbecoming, but if you’d like to search for some, knock yourself out]

Tragically but predictably, this results in the frequent exploitation of High Desire To Pass Tests people when confronted with the opposite psyche. If one party to a conflict chooses “Monkey Dance” every play and the other chooses “disengage”, then the endgame is inevitable.

Pictured: The endgame. Refer to the footnote [99] below if the psyche of initiating conflict on another person & its implications remains unclear.

You don’t need a PhD in game theory to understand that if it becomes known that you’ll submit in every round of the Monkey Dance, you get asked to play a lot more rounds of the Dance.

Resolving Conflict: Cardinal Sins vs. Iron Rules

For the high Desire To Pass Tests kids, the ones who aced the marshmallow tests, the non-aggression principle is a no-brainer. The system already prohibits violence by default!

Conflict resolution for these kids will therefore tend to be achieved through social negotiation and ideally reinforced by an external authority’s judgment. Consensus is key, because consensus a) validates their personal actions and b) is the only legitimate means by which the teacher external authority can be sanctioned to act with force. It’s force…at a distance.

So when they’re subjected to direct conflict, their first instinct will be to appeal to others. Like the lawyer who turns to the judge while Lil Wayne harasses him, they will usually end up frustrated by this experience, because the Judge thinks exactly what we read earlier:

"it's best just to back down from them... because that's they way thems are."

After this mode of thinking is fully internalized, their role in any future conflict is automatically self-cast as the victim, which usually does lower their psychological pain by removing rage-inducing feelings of impotence and replacing them with serenity. However, per footnote [99], it tends to increase their chance of future victimization.

These images below are a bit of a scissor statement online: to genuine believers, they truly represent psychological transcendence over base personal desire and lack of power. To others, they represent submission and impotence. Self-mastery vs. mastery of others. Each perspective seems alien to the other.

You either get it or you don’t.

For high Desire To Pass Tests kids, the cardinal sin is escalating conflict.

“Participating in ‘the monkey dance?’ Lol. Kind of derisive to suggest I’m an animal, no?.” - a fellow primate.

Successful de-escalation is the defining class marker here.

It signifies moving up to the next rung on the Course of Honors. It demonstrates system-priority over personal-priority. It shows Christ-like self-control. To be challenged directly with conflict and refrain from responding in kind?

It’s as if the marshmallow talked to you and said “eat me!” and you still didn’t reach for it!

True self-mastery.

Reaching such a state of enlightenment can, perversely, feel good — each act of perfectly executed self control gives you a small rush, much like the one hotelconcierge described when talking about his own anorexia. He didn’t set out with the goal of starving himself. He just slowly started to enjoy the feeling of acing a test of willpower, the feeling that even personal suffering couldn’t make him fail the test.

Emotional self-regulation in this environment — per the two images above — is the necessary first step in non-escalation. Watching another kid stuff his face with the first marshmallow is awkward and embarrassing, something to avert your eyes from. You don’t look away because you think eating marshmallows is gross.

You look away because someone just failed a standardized test in public and you feel shame on their behalf, even though they don’t!

But ask the obvious follow up question: who does this person, the high Desire To Pass Tests kid who has attained self-mastery and the ability to de-escalate potential conflicts, judge more harshly: the boy who displays high levels of violence from the start and signals a low ability to resist the marshmallow, or the boy who is perfectly self-controlled and displays no aggression…right up until a potential conflict escalates to a certain level, at which point he opts into the escalation game with a display of shocking violence?

Which one of those two violated his expectations more?

Do you judge the boy who shows no capacity for self-restraint? Or the boy who shows the capacity but not the willingness?

Differing opinions on this question are at the heart of local, national, and even geopolitical disagreements.

Shame & Society: Fake Tales of San Francisco

What’s the difference between guilt and shame?

If you ever need a dictionary definition, use the 1828 Webster’s dictionary:

We see that guilt requires someone acting of their own free will, knowing right from wrong, and then choosing wrong anyway. The guilt exists as soon as the wrong choice was made.

The child with a high Desire To Pass Tests feels guilty for not studying “enough” — though of course no amount of studying could ever assuage that feeling. The guilt occurs because the child violated their own standards, and it occurs immediately anytime the child makes the wrong choice. It is a deep and painful and private thing.[2]

Feelings of personal guilt motivate the child to comply even harder with his own value system.

Guilt is a personal emotion that, in the most positive light, pushes the child to be the best version of himself.

On the contrary, we see that shame is a more social emotion:

Every example given of shame by Webster is about how one is perceived by others.

As a social emotion, shame motivates the child to comply with the value system of others. If the child shares the same value system, then he also feels guilt, yes. But sharing the value system is not required. A mere awareness of how others will react is sufficient to generate shame in those sensitive to social value.

In this way, plenty of children and politicians alike are able to express genuine remorse and true regret when caught in the act of a bad deed that they would gleefully do again if they thought they could get away with it. The shame they feel is true and real — but it does not require them to share society’s value system, only the ability to model it when caught.

Shame is a social emotion that, in the most positive light, allows society to increase the compliance of those who are smart enough to know better.

What does this have to do with San Francisco?

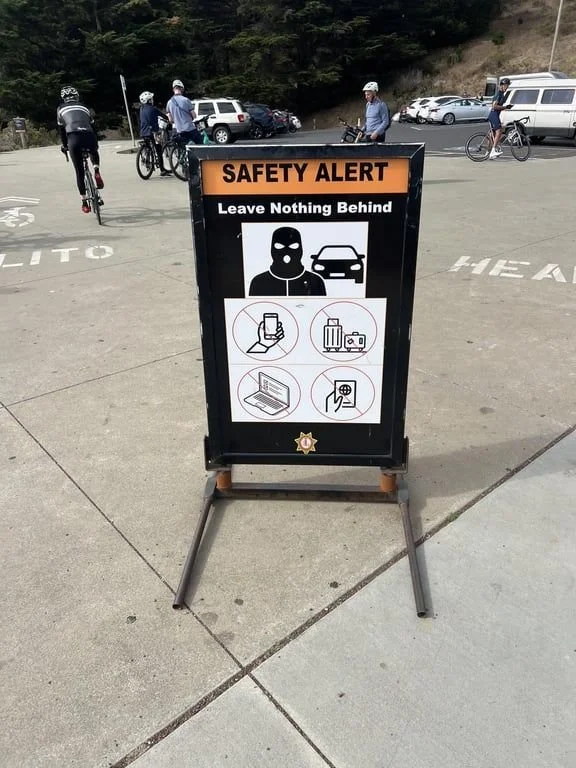

I discussed above the feelings of guilt that high Desire To Pass Tests kids feel when they‘re involved in crime — even as victims. “I should’ve known better” is the very first thought they have when they return to find their car window smashed in.

Pictured: I should’ve known better, March 2022. No, I didn’t file a report.

But guilt is a personal emotion. It can only ever generate additional actions in line with personal values.

Shame, on the other hand, can cause people to take actions that are not aligned with their personal values. Even actions that go directly against said personal values. And if they’re the right sort of high Desire To Pass Tests kid and they follow through with them, they’ll actually feel good about doing so — after all, what just happened?

They directly overcame a personal preference in order to satisfy an external authority and accrue a personal reward! Whether they get status, honor, respect, etc. is irrelevant, anything will deliver the high.

If you don’t get it still, you can watch Batman Begins or read my 3,000 word twitter thread explaining the moral philosophy of early 2000s Americana:

I offer great thanks to the 150+ souls who read all 95 tweets in this thread, I will buy you a coffee anytime

And you have to understand all this, the marshmallows and big tech and shame, in order to understand why San Francisco executed a temporary urban crackdown last month, in November 2023, generating the largest year-over-year crime reduction in recent records:

Pictured in the background: “lol, lmao, he said it, he’s not wrong though”

People on both the left and the right who don’t understand the way shame works tried to use this clip to score political points on Newsom. But it didn’t really work. Because he’s being honest and the thing he’s being honest about — “we would be ashamed to have our ally, the esteemed (dictator) of China, Xi Jinping, come to our beautiful city and find it unworthy of his own values, see it looking grim, and have his staff experience the urban background of constant theft and drug overdoses and low grade criminality that is our norm, because to him this would signal a lack of power instead of the transcendent self-restraint it truly represents” — is broadly felt and understood by his base.

And that base has the same values as everyone who watched & liked Batman Begins, which last time I checked was ~America.

From the broadly left, the critique of Newsom’s temporary actions is that they obviously do not solve the underlying problems that cause crime…and that he used the heavy hand of armed state forces to accomplish his goal.

Note that neither of these critiques have any relevance to the shame that motivated Newsom’s actions — they are instead reframings of guilt likely already felt by Newsom and his base. That he cannot solve a housing crisis, a drug crisis, a crime crisis, a local retail economic crisis, and a breakdown in public order is felt as a source of personal failure — and I write “he” here but really I mean “we” — and therefore a source of much guilt. But overcoming personal preference was already baked into the act! You’re telling the anorexic that they aren’t getting enough protein — if your words have any effect at all, they merely elevate the act further.

You can’t change his actions by trying to make him feel more guilty about it. And you lack the social status to compete with Xi Jinping’s ability to shame him.

“He should care more about his base than a dictator!”

Sure, maybe in a perfect world, but “his base” codes as “parents”, and “a dictator” codes as “teacher”, and only one of them is grading the test, so really, whose method of long division are we gonna use??

“Creating Economic Opportunity” as a slogan behind 4 heavily armed police officers is a bit too on the nose, eh?

And from the broadly right, the critique of Newsom’s temporary action was that he “only” cleans up the city when a foreign world leader with explicitly different values from San Francisco’s comes to town, but otherwise remains unwilling to use the implements of the state to reduce crime within the state.

That is: he prefers the city live with a certain level of crime and can only be motivated to lower it via the social shaming of people who don’t live in the city. He therefore chooses crime over not-crime.

But note that there’s not actually any attempt to understand or persuade otherwise in this critique. Newsom’s power was in stating plainly: “That’s because it’s true.” Critiquing him by reiterating what he already said does not undermine his position among his base — it strengthens it!

He wants to eat the marshmallow, but the thought of doing so causes him moral disgust…He is able to control himself. He is unable to act on his own desires. He is destined to succeed — because he was told to. He will never be happy.

The only ways to overcome shame are by rejecting the social hierarchy entirely and casting aside one’s Desire To Pass Tests or by replacing it with an even greater shame.

The former is nigh impossible for adults whose development is already locked in, although some twitter friends claim psychedelics can help [editor’s note: conrad does not endorse such claims].

And as for the latter…I’m not sure who you could get with more global social status than the leader of our biggest geopolitical rival. Nor how you could convince them to make regular visits to San Francisco.

All that said, there’s one analysis I didn’t see among all the hubbub of political point scoring.

Control & Responsibility: True Tales of San Francisco

See it turns out, San Francisco’s Police Department reports up to date Crime Data, by week, on what might be the internet’s most advanced interactive crime dashboard, including year-over-year comparisons to track performance.

Which means we can ask: what did San Francisco’s crime look like from January 1st 2023 to October 31st 2023 — the first 10 months of the year?

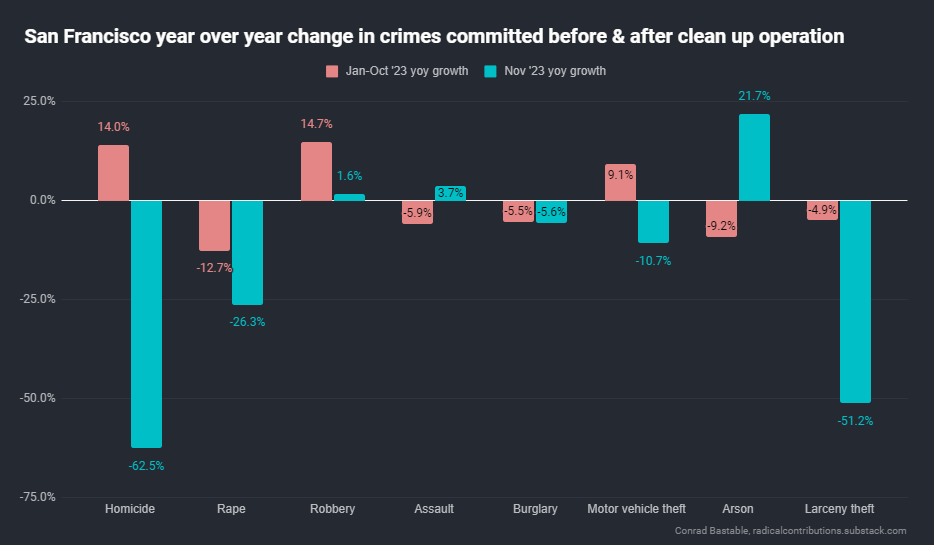

Note the year-to-year increase percentages source

In isolation, this means nothing. Are these numbers high or low? Relative to what standard? Can they even be changed? Alone, they tell us nothing.

But the obvious question is: what happened in November? The San Francisco Standard has photos showing Newsom’s efforts were underway by November 3rd, and California Family notes things began sometime in October.

Did “cleaning up” the city actually have any impact on crime?

Comparing these two screenshots is a bit awkward, so I’ve put the “Year-to-Year % Decrease or Increase” column data side by side in a bar chart below. This is the column you want to use because it helps adjust for any potential seasonality in the data (e.g. humans tend to do more killing in the summer).

In this case, a negative number means fewer crimes occurred this year compared to last year. A positive number means more crimes occurred. The blue bars are post-crackdown. The red bars are status quo pre-crackdown.

To know if Gavin’s aggressive armed-police-enforced “clean up” had any impact on local crime rates, compare the blue bars to the red bars.

Hopefully this cut of the data is simple and easy to understand. There was a small uptick in assault and a substantial increase in arson. No meaningful impact on burglary. And very significant declines in all other crimes.

Of course, it goes without saying, there are many variables at play in such overdetermined areas as aggregate crime. But these two snapshots let us ask two interesting questions:

i) how many people were victimized from January to October of 2023 that would not have been victimized under a hypothetical “one-week-a-month Gavin Newsom reign of state tyranny”?

ii) how many people were saved from victimization in November by the aforementioned reign of tyranny?

Given that we have simple, clean data for both periods, I can do some very basic math to look at the year-over-year changes in November’s crime rates and apply those same year-over-year changes retroactively to the January-October historical period, and discover that if Gavin had rolled out the troops once a month in 2023, San Francisco could have hypothetically had an increase in assaults and arson, in exchange for about 30 fewer homicides and rapes, 250 fewer robberies, 1,000 fewer stolen cars, and 14,000 fewer thefts.

I might hypothesize the arson and assaults as directly related to both the increased use of force by the state itself, as well as protests surrounding November’s APEC conference, which included vociferous protests around China and the unfolding Israel/Palestine conflict, but again, there are many variables at play.

And doing the inverse math for November, we see that if Gavin had not been moved by shame to tyrannical action, San Francisco might have experienced: 6 additional homicides, 3 additional rapes, 25 additional robberies, 18 fewer assaults, 109 additional stolen cars, 7 fewer arsons, and 1,537 additional thefts in November.

I know it’s a bit dry to write this all out in words, but I think there’s a certain weight to me having to write “30 fewer homicides and rapes” instead of just slamming it all in a bar chart for you to read. That said, here you go:

This chart applies the year over year changes in crime above to the full 11 month period, showing the number of crimes committed under a hypothetical world where Newsom never “cleaned up” San Francisco in November compared to those committed in a world where he did so once a month for the full period.

The methodology is simple: for the red bars, take the actual historical data from January-October and then sum it with the 2022 November data grown at the actual year-over-year growth rate from January-October 2023. That gives you an 11-month period accounting for year-over-year changes that happened in 2023 as if Gavin’s crackdown never happened.

And for the blue bars do the inverse — take the actual historical 2023 November data under Newsom’s crackdown efforts, and then sum it with 2022 January-October period data assuming the crackdown year-over-year growth rate that occurred in November 2023.

Of course we should really slice this chart up into two charts, like Wikipedia does, one for violent crime:

…and one for property crime:

What I like about this analysis after-the-fact is that it suggests there is no free lunch.

For the first 11 months of the year, the price of 39 fewer homicides, 33 fewer rapes, 300 fewer robberies, and 1,000 fewer car thefts, hypothetically, would have been 231 additional assaults and 85 extra arsons.

A Season For All Things: Data

In my essay exploring the failure of YIMBYs to understand Japan’s real estate market, I mocked writers who choose to represent time series data as simple bar charts, thereby obfuscating the actual shape of the underlying trends.

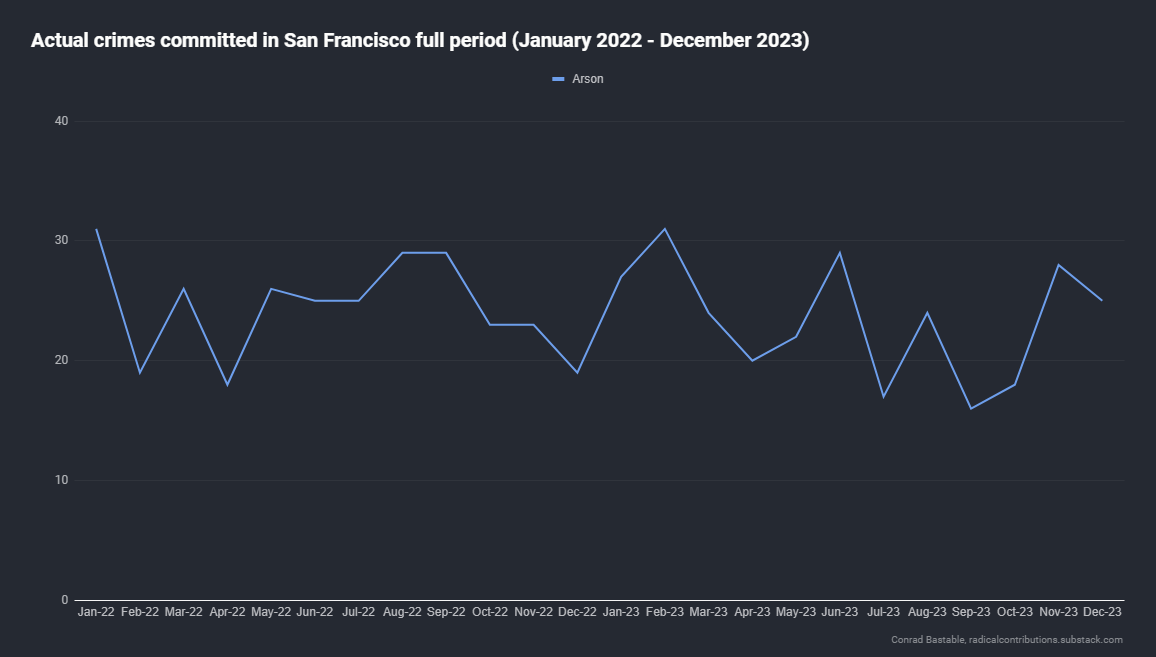

In showing you a “constructed” metric above and a simple bar chart showing year over year crime changes, I fear I am already guilty of the same vice, but before I become more so, allow me to show the full & proper data set in monthly intervals over the last two years:

Pictured: Shame in action

Of course, taking all that data and graphing it on the same axis makes it hard to see what’s going on, because the Theft data swamps the rest. I will assume you can clearly see that Theft fell far below it’s prior 2 year low after Newsom’s crackdown began in October.

Let’s reduce the upper-bound of the y-axis to reveal trends in the other crimes.

Below we see Motor Vehicle Theft, Burglary, Assault, and Robbery mirroring the Theft trend, with some of the lowest number of crimes reported for November and December in recent years:

Lastly — and thankfully these are two of the smaller numbers in the dataset — we have Homicide and Rape:

Again, the trends are the same.

Again, the October Crackdown for a conference in mid-November had a lasting impact through the end of December on crimes from Theft to Rape, Burglary to Grand Theft Auto.

For the curious, the rape figure for the December immediately after Newsom’s Crackdown was the same as during the height of Winter 2020’s lockdown covid season when the city was dead and everyone trapped at home, and a third of what it was back in December 2017.

[Note: Arson numbers were included in the composite chart above but have been removed from the Homicide & Rape chart as they overlapped substantially with the Rape numbers, and I feel that Arson and Rape are different categories of crime, with the chart made worse by showing them together. It’s included in the footnotes for completion’s sake]

I’ve said a few times in this piece that violence and crime are multivariate, and if someone wishes to challenge my analysis by noting that a San Francisco with zero inequality, perfect access to public resources, no drug problems, and infinite material abundance would have lower rates of violence and crime, I am happy to concede the point entirely — to my knowledge, such an A/B test has never occurred in a single month while keeping all else equal, but if it does, I promise to write about it.

What’s fascinating here is precisely the A/B test we just got, the psychology that motivated it, and the underlying economic factors that forced us all into this wild experiment.

In Summary: Wealth Über Alles

I strive to keep “advocacy” out of my writing, as I’ve said on multiple occasions that I find it tends to corrupt analysis and distort interpretations of reality. This piece is no different. Whether or not you find the idea of a monthly Newsom Police State appealing or horrifying is up to you. There’s a tradeoff either way. I’ve intentionally tried to use extreme language to describe it, lest any reader misread me and think there’s a free lunch on the table.

Pictured: more guns in the lobby of my San Francisco hotel than have ever been in said lobby before — does living in a perpetual police state sound like fun to you?

But even though this essay uses San Francisco and Venice as examples, it’s not really about those two cities.

It’s about how the preferences of the local elite shape shape every society.

And it’s about how the type of elite you ultimately end up with depends on the dominant mode of Wealth generation in a given region.

Putting it all together, your modern day Course of Honors selects your elites not just for ability — but also, and perhaps primarily, for the individual psychology willing and able to ace your tests. The more contortions you demand, the more compliance you select for. The more agency you demand, the more aggression towards peers you select for.

It is impossible to select any human for ability without also selecting them, in aggregate, for character.

Look again at Rome’s Course of Honors:

We don’t have these titles anymore. But there’s a map that looks like this in engineering roles. And there’s a map that looks like this in sales roles. And healthcare. And investing. And in Hollywood. And in Academia. And in industrial factories.

Each city has its own map of elite-hood, based on the dominant industries in that city. And because of the nature of economic specialization and the opportunity cost of operating in the second-best industry in town, each city will become dominated by a tiny handful of industries.

Often a single source of productivity will drive a whole region.

Each Course of Honors rewards those with The Desire To Pass Tests…but also prioritizes different underlying skillsets. The population of that city will begin their tests with a differing baseline Ability To Pass the Test.

The intersection of those factors — whatever it takes to succeed in a given city, and therefore a given profession — ultimately determines the distribution of personality types and philosophies that come to dominate the upper echelons of each city.

That’s a lot of words to say: it takes a very different sort of person to be an L7 Software Engineer at Google compared to a senior manager of an oilfield compared to captain of a merchant ship in 1453. This is a very soft essay, intentionally lacking many of my usual charts and tables. I feel naked without them. But this isn’t the kind of essay that’s made better by numbers. It’s about faces.

And if you scroll back quickly through this essay, you’ll see a lot of different faces looking back at you.

Societies are about people. Violence happens by people, to people.

Real people, with faces, hopes, and fears. These people:

Reminder: every one of these faces failed the test.

When I was younger, I was fond of the phrase “the state has a monopoly on violence.”

A compulsory political organization with continuous operations will be called a 'state' insofar as its administrative staff successfully upholds a claim to the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force in the enforcement of its order.

As some of the ideas in this essay — and others not included for brevity! — have percolated in my head for a few years, I’ve come to also appreciate the inverted framing:

“All use of violence is sanctioned by the state.”

Both statements are extremes and untrue. But, like with calculus, you can understand a lot about a system by considering its extremes, even if your true goal is to balance the ethic of moral conviction with the ethic of responsibility.

Your city’s specific modern-day Course of Honors selects an elite, who shape its politics, which deploys the violent resources of the state & their own households, which shapes the level and mode of day-to-day violence that inhabitants are subjected to.

This framing is not perfect. It has gaps. It is just one way to look at the world.

Obviously it goes without saying that you can layer on top of this framework meta-level differences in national cultures and national proficiencies, and in the level of background wealth that supports differing levels of state capacity and all sorts of other things.

“Just increase GDP and add a million jobs and provide great access to those jobs, plus great education, while reducing cultural encouragement of any violent act” is a hell of a pitch. It would maybe work. I’m not sure what sort of an elite would be necessary to enact such a world, nor what the character of elite such a world would select for. A friend just visited Singapore and tells me it’s nice, though I’m not sure paying $100k for the temporary privilege of owning a car appeals to me.

Regardless, rearchitecting our society is a project for the utopians — my own project with these essays is more suited to the mundane, to analyzing the world and describing it clearly and without varnish.

And that analysis cannot help but see all the ways that every part of society is downstream of economics, not in the bland aggregated sense of numbers & GDP per capita tables that academics and activists and journalists love, but in the very specific modes of value creation that comprise what we call “business”, “industry”, and “building things.”

For those with both the mind and the hands to climb the Cursus Honorum, whatever shape it takes for you, I wish you good luck.

May your mind keep you out of trouble, and your hands keep trouble out of you.

Mens et manus.

Pre-notes note: though I’ve said multiple times in the essay that the point of it is to discuss the role that selecting a regional economic elite has on that region’s perspective towards crime, I fear some readers may still desire to discuss the object-level state of crime in San Francisco in depth. I will share any and all cuts of the weekly SF crime data that people may be interested in at this source location here — but I will concede any object-level points anyone wants, even contradictory ones, if it helps me avoid debating what “SF should” or “should not” do. The tragic takeaway from this essay ought to be that what "SF should” do is irrelevant, all that matters is what “SF can” do, and the surface area of options there is downstream of the way you become an elite in San Francisco. See above for more info.

Notes

[0] The relative complexity & illegibility of these status ladders to “the plebs” is often a hidden sign of elite status. Getting into Google in 2014 was good and your could tell your family about it. But to people in the Bay Area, getting into Y Combinator was often better. This seems like a small aside, but obfuscating your true power level is a key part of the elite game in any society that doesn’t have a rabid devotion to pure meritocratic advancement.

Which is a fancy way of saying: it’s best if the mob doesn’t know your name, where you live, and where your office HQ is. I know some handful of readers will read my previous paragraph and immediately react: real elites have better options than those places! That’s the point.

See also: Occupy Wall St setting up camp on Wall St itself after the 2008 crash instead of the place where the banks actually do business…and the eventual lack of consequences for those involved.

[1] This runs somewhat counter to modern parenting norms in elite circles, which come in many shades but always resolve to prioritizing a self-conception in your child as a “striver” as the most important factor.

Wealthy parents are terrified their kids will end up as “spoiled trust fund kids,” who just piss their inheritance away with nihilistic self-destructive consumption. Social climber parents who don’t feel they themselves have quite “made it” yet are equally terrified that their kids will be satisfied — and in that satisfaction, resign themselves to mediocrity. Both archetypes are common in America’s upper class. Both try to fill their kids with the Desire to pass tests above all else.

My counter-proposal is to instead try to integrate both the Desire and the Ability to Pass Tests.

My sense is that success here is nearly impossible.

But perhaps it is better to fail in the attempt of something worthwhile than defer to the most common habits of others. Particularly when those habits irk me so much.

[2] When someone volunteers to you that they “feel guilty” about something, it’s therefore wise to assume that they do not in fact feel guilt. They instead feel they might be perceived to have acted badly and are asking you to validate them, to confirm (or lie) that you do not judge them, and to allow them to be from shame.

[42] As promised, the Arson data I removed from the Homicide/Rape chart, showing the uptick in November discussed in “Control & Responsibility: True Tales of San Francisco”, before dropping slightly in December but still remaining elevated above recent levels.

My hypothesis that this is related in some way to the crackdown itself is merely a hypothesis, but I continue to find the increase in Assaults & Arson to be interesting and relevant given the clear drop in other crimes.

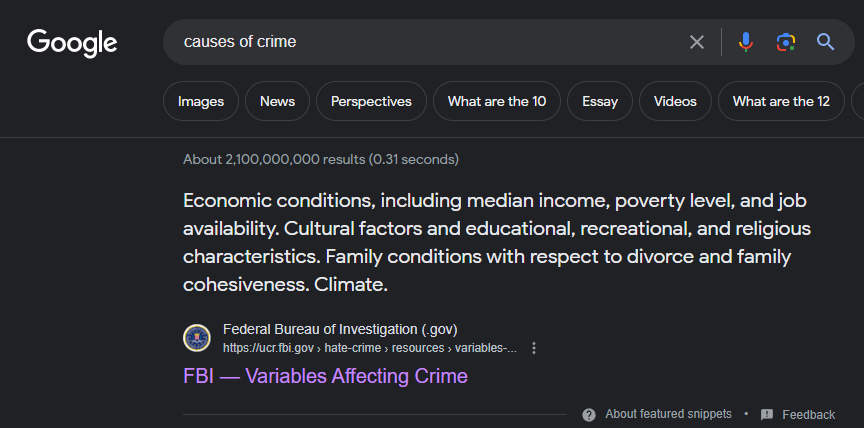

[75] While looking for a snappy image after writing this essay, I discovered this amusing result on Google. I searched for “causes of crime” and received this featured snippet:

and what’s fascinating is that the very first part of this snippet, the first words Google shows me in answer to my query, is “Economic conditions, including median income, poverty level, and job availability”

and yet, if you visit that FBI page, you’ll see quite clearly:

that the snippet Google surfaced begins halfway down the list, below factors such as “degree of urbanization”, “youth concentration”, and “stability of the population”.

I wrote earlier about seeing different worldviews when they collide with your own and generate friction.

I can’t help but comment here, in the footnote, about Google’s algorithm boosting “Economic conditions” above the FBI’s own top ranked bullet, while linking to the FBI as a resource. Obviously BOTH of these resources conflict with my own worldview, presented above in this essay, but seeing them both conflict here in a small but meaningful way amused me.

[99] On the subject of Eve Online — a hyper niche multiplayer online game about spaceships I once played in my youth — I want to to explain exactly how it applies to this topic and why I lean into it as a metaphor for understanding conflict.

When I played, I usually described my personal gameplay loop as “making a commodities market to fund a hobby hunting deer, except sometimes the deer have friends, and sometimes the friends have railguns.”

It sounds silly. A fun game. But it’s hard to describe the stakes involved, the very real consequences of personal loss — both in time invested and direct financial investment — that accompany any failure.

How do you navigate a situation where the cost of misjudging a situation costs hours of time and hours of minimum wage dollar equivalents?

Preparation. You pre-plan potential moves and escape routes. You observe the target as long as you can. You stalk them to learn their patterns — and you apply the knowledge gained from each prior stalking to every subsequent one, looking for matches or aberrations in behavior.

But it goes deeper than that — every single kill you’ve ever been a part of in game is saved forever on a giant online scoreboard.

Which means the first order of business upon discovering a potential target is to pull up their history.

It takes about 1 to 5 seconds to pull up, depending on how fast you can alt-tab. If you see something like this, you ought to pause and double-check your exits and give your surroundings another scan:

89% Dangerous huh?

The “Dangerous-Snuggly” scale is rather helpful.

The “Gangs-Solo” scale suggests this target could be alone. But they might not be.

But what if you instead see something like this?

100% snuggly

0 kills, ever. No friends, ever.

19 lost internet spaceships — for a combined value of about $5 (at the time).

An online friend recently said to me: “I think anyone who commits murder is in some sense a psychopath.” Which may or may not be true, depending on your definition. But believing that also frees you from having to introspect into the mind of a killer and see the world the way he sees it.

Thankfully, internet spaceships aren’t real and the potential for purely-digital unplanned violence is part of the game’s niche appeal. Which means I can say without reservation: a scoreboard that shows the world you have been previously victimized increases the likelihood you will be victimized in the present. In game.

This is one of those things that is so deeply unfair, so unpleasant, that it calls into question one’s faith and principles if they are weakly held.

Nonetheless. Even when I have every single advantage, even when my target lacks any weapons, even when I’ve stalked them for 3 nights in a row and have bookmarks placed in space at all their favorite locations….even then. I will pounce on them more quickly if they have a track record of losing. If they’ve ever killed someone who uses the equipment I use, I’ll hold my position for hours longer, days longer, just to make sure I’m not in danger.

Is the predator a coward?

In many ways, yes. Like Adam in the Garden of Eden, it is the knowledge of good & evil that fills the hunter with anxiety. Every unfair step he takes to move the odds of success in his favor…is a step he becomes intimately aware of, and in doing so he also becomes aware of the potential for a third-party to do the same back to him. Yes, the predator is afraid. The very act of predation hinges on creating the most unfair fight imaginable.

“Don’t you want to fight fair?!” No idiot, I want to take your stuff (in game).

The “knowledge of the moment to come” in Eve Online is unlike anything else you can get in video games. The symptoms of full-body anxiety before any conflict has occurred — hands shaking like crazy, breath caught in your chest, legs twitching a mile a minute — are so common you can mention “The Shakes” online and everyone knows what you mean.

This is the mindset and mindstate of a man about to initiate conflict upon another when he knows doing so risks his own hide.

It is not exactly fun.

But there’s nothing else like it.

Of course none of this has any bearing at all on the psychology of actual conflict in real life and I’ve not played the game for a decade at this point. I just thought some readers might find it interesting in the broader context of this essay.