2010 was the year Silicon Valley lost the war in China. It took another 5-6 years for the rest of the playing field to realize the war was already lost (shoutout Uber & Facebook), and most of the commentariat still don’t quite understand the Trillion-dollar nation-defining stakes that were, for a brief moment, in play.

2010 marks the date Google pulled out of China, conceding both the economic and moral high-grounds.

By the transitive property of Identity, Google → Silicon Valley → the United States of America, this was the battle that defined the limits of an empire. Most people missed it. Most still think Google didn’t even have the option of going to war. Most think the conflict was entirely about Censorship and nothing to do with Protectionism.

Most think Google could not have penetrated The Great Firewall.

I suggest that they could have, and in doing so forced a confrontation to defend both their Ideals (Freedom of Information) and their Business (the Chinese market). That they did not has shaped the last decade of Tech growth — and will shape more than just Tech over the next decade as China's Tech sector goes Global.

Date: 2015; Symbolism: heavy; Facebook chances in China: zero

The King Is Dead, Long Live The King

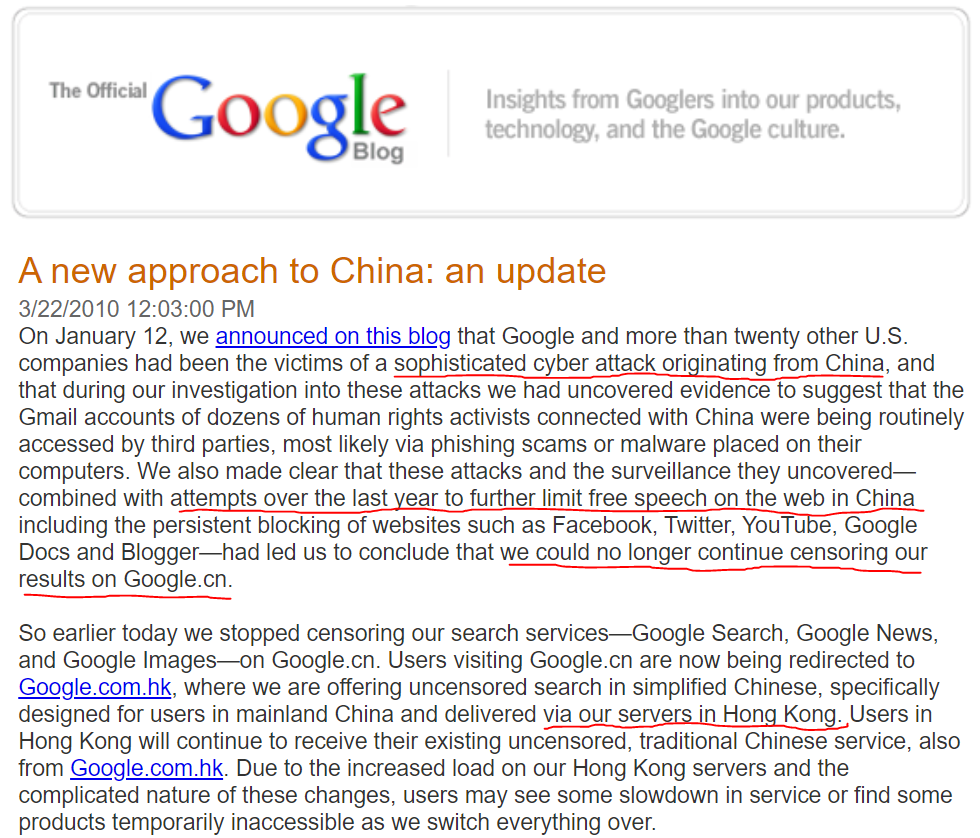

The instinctive decision to place their censorship-dodging servers in neighboring Hong Kong should not be ignored either — it should help “contextualize” China’s recent attempts to exercise political power over Hong Kong source

Many readers took this as Google taking a “strong & proactive” stance against Censorship, instead of the reality: Google giving up on the Chinese people and the Chinese market.

The blog-post itself also contains this absolute gem of wishful thinking:

…We believe this new approach of providing uncensored search in simplified Chinese from Google.com.hk is a sensible solution to the challenges we've faced—it's entirely legal and will meaningfully increase access to information for people in China. We very much hope that the Chinese government respects our decision, though we are well aware that it could at any time block access to our services.

Hindsight speaks for itself on that one.

Western media outlets at the time put a positive & proactive spin on the story, with headlines like: Google Defies China on Web Censorship (CBS), Google lifts censorship of Chinese search engine (The Independent), Google stops censoring Chinese search engine (The Guardian), and Why Google Is Quitting China (Forbes)

The New York Times had perhaps the most somber perspective, including this prescient quote in their coverage:

“It is certainly a historic moment,” said Xiao Qiang of the China Internet project at the University of California, Berkeley. “The Internet was seen as a catalyst for China being more integrated into the world. The fact that Google cannot exist in China clearly indicates that China’s path as a rising power is going in a direction different from what the world expected and what many Chinese were hoping for.”

While other multinational companies are not expected to follow suit, some Western executives say Google’s decision is a symbol of a worsening business climate in China for foreign corporations and perhaps an indication that the Chinese government is favoring home-grown companies.

This was written way back in 2010, so why did it take an extra half-decade for the other major players in this game — the exec teams at Uber, Facebook, etc. — to realize the door was closed?[0]

A Picture Tells A Thousand Words: A Tale of Two Stocks

Here’s Google’s stock price for the 2 year period following their surrender to the CCP:

date range set to 1/10/2010 - 1/10/2012 source

And here’s Baidu’s for the same time period:

same date range as above source

Of course I can make a stock price chart say anything I want (shoutout to my investment banking career, email/DM me for tips), and nobody should take this as conclusive of any Narrative in particular. The mark of a charlatan is deriving single-variable causation from a chaotic world. So let’s actually dive in on the context here.

Screw A Picture, Here’s A Thousand Words

There’s one more article on Google’s battles with the CCP that I want to mention, also printed in The New York Times and written by Clive Thompson, but way way waaaay back in the grim dark ages of 2006, 4 months after Google’s first decision to censor itself and begin the process of conceding to the CCP.

From the article, here’s Google China’s Head of Operations, Kai-Fu Lee, on the merits of democracy (all emphasis in quotes below is mine):

…as Lee and I talked about how the Internet was transforming China, he offered one opinion that seemed telling: the Chinese students he meets and employs, Lee said, do not hunger for democracy.

"People are actually quite free to talk about the subject," he added, meaning democracy and human rights in China. "I don't think they care that much. I think people would say: 'Hey, U.S. democracy, that's a good form of government. Chinese government, good and stable, that's a good form of government. Whatever, as long as I get to go to my favorite Web site, see my friends, live happily.'

It sounded to me like company spin -- a curiously deflated notion of free speech. But spend some time among China's nascent class of Internet users, as I have these past months, and you begin to hear such talk somewhat differently.

As Clive says, Western readers were unable to hear such words as anything other than “company spin”. They expected, in their heart of hearts, for a grand liberalizing revolt in China. We expected, publicly and rather smugly, Chinese people to see the error of their government’s ways when they learnt about our magnificent system, much like the Soviets did.

You really ought to pay more attention to the bold parts in that quote and treat them seriously. That quote is 14 years old — whether it was true at the time or not, it represents the only publicly-expressed internet culture that today’s Chinese teens have ever known. Teens shape internet culture, so what might have been mandated via top-down directive ~15 years ago becomes the natural state of things in the present.

Panem et circenses, on the scale of ~1.5 billion people, works and will continue to work, and you won’t get your revolution unless they run out of panem or circenses. I know we Americans like our #Values and our #Principles, and I’m no exception, but sometimes I fear we drink our own kool-aid and forget that the impetus for our own #Revolution was an economic one.

Speaking of circenses, here’s the CEO of Google’s chief Chinese competitor on the value of Intellectual Property:

Baidu's executives discovered early on that many young users were using the Internet to hunt for pirated MP3's, so the company developed an easy-to-use interface specifically for this purpose…Almost one-fifth of Baidu's traffic comes from searching for unlicensed MP3's that would be illegal in the United States.

Robin Li, Baidu's 37-year-old founder and C.E.O., is unrepentant.

And here’s Sergey Brin himself articulating the CCP’s Tech Protectionism strategy all the way back in 2006:

In 2002, though, something changed, and the Chinese government decided to shut down all access to Google. Why? Theories abound. Sergey Brin, the co-founder of Google, whose responsibilities include government relations, told me that he suspects the block might have been at the instigation of a competitor -- one of its Chinese rivals.

Brin is too diplomatic to accuse anyone by name, but various American Internet executives told me they believe that Baidu has at times benefited from covert government intervention. A young Chinese-American entrepreneur in Beijing told me that she had heard that the instigator of the Google blockade was Baidu.

"Basically, some Baidu people sat down and did hundreds of searches for banned materials on Google," she said. (Like many Internet businesspeople I spoke with in China, she asked to remain anonymous, fearing retribution from the authorities.) "Then they took all the results, printed them up and went to the government and said, 'Look at all this bad stuff you can find on Google!' That's why the government took Google offline."

Baidu strongly denies the charge, and when I spoke to Guo Liang, a professor at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in Beijing, he dismissed the idea and argued that Baidu is simply a stronger competitor than Google, with a better grasp of Chinese desires. Still, many Beijing high-tech insiders told me that it is common for domestic Internet firms to complain to the government about the illicit content of competitors, in the hope that their rivals will suffer the consequences.

In China, the censorship regime is not only a political tool; it is also a competitive one -- a cudgel that private firms use to beat one another with.

And here I thought I was articulating something at least somewhat novel and outside the mainstream view with my Industrialism essay. Still, I find it odd how this understanding of the CCP’s politico-economic “cudgel” managed to go from The New York Times in 2006 to a somewhat fringe belief in 2018.

It’s as if the evident present-day success of China’s Tech industry is taken by many as a post hoc validation of an assumed prior meritocratic success. Translation: Capitalist success is taken as proof of free market fitness. Translation: We assume winners deserved to win.

I’m not saying they didn’t deserve it. Success on the scale of a whole industry requires a union of business leaders, politicians, workers, landowners, energy providers, etc. etc. etc.. It’s the most multi-variable, multi-faceted game there is, and anyone who knows the history of Silicon Valley knows it begins with the US Military.

But if you’re running a US-based Tech business, you should know the incentives of international politicians do not necessarily align with your own. The playing field is never level.

Lastly, here’s my favorite quote on how seamlessly a Communist Dictatorship co-opts the tools and methods of Capitalism:

From his seat on a plush sofa, Ma explained Alibaba's position on online speech. "Anything that is illegal in China -- it's not going to be on our search engine. Something that is really no good, like Falun Gong?" He shook his head in disgust. "No! We are a business! Shareholders want to make money. Shareholders want us to make the customer happy. Meanwhile, we do not have any responsibilities saying we should do this or that political thing. Forget about it!"

Imagine getting out capitalist’d by communists. Shed a tear for those who thought economic liberalization would lead to political liberation:

“Change is the main event in China, and America should welcome it. Chinese hard-liners will not be able to stop the coming political reform…”

Idealists Draw The Playing Field, Pragmatists Play The Game

Idealists are people willing to die on a hill.

No Pragmatist would ever do something so idiotic.

Conveniently for all the hills out there, the world is mostly full of pragmatists.

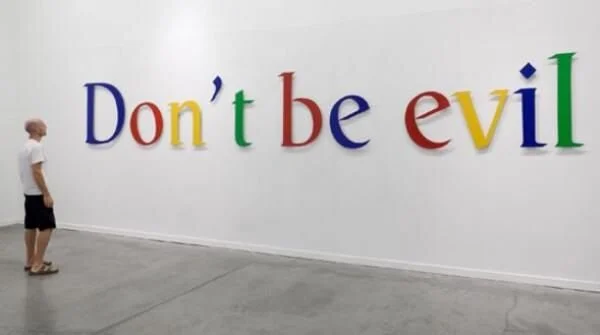

My contention is that the CCP killed the Idealist-Google, ostensibly on the hill of Censorship but in reality on the hill of economic profits from Chinese citizens. What remains is a Pragmatic business.

The core change in philosophy is that, when push comes to shove, post-2010 Google now agrees with Jack Ma:

"No! We are a business! Shareholders want to make money. Shareholders want us to make the customer happy. Meanwhile, we do not have any responsibilities saying we should do this or that political thing. Forget about it!"

And it’s not just Google who learned this lesson.

It is this exact statement / attitude / philosophy that enables “The Rise of Woke Capital” (also New York Times): corporations all over America can be forced to adopt the Ideals of anyone exerting economic leverage.

The irony of “Woke Capitalism” is that it only works in an era when the Capital itself is a-moral, judgment-free, value-less, willing to conform to the demands of the highest bidder. When Idealists force a surrender from a business on the basis of economic profit, don’t be so quick to celebrate.

Just be glad a less well-intentioned Idealist didn’t get there first.

A number of my very best friends currently work at Google, so don’t think I’m singling out Google here from spite or a lack of sympathy for their position between the hammer and the anvil. You can read the full culture-clash article to see how Microsoft unpersoned Jing Zhao or how Cisco laid the first "bricks” for The Great Firewall. Google's not an outlier here — but it is a figurehead.

If mighty Google cannot stand against the CCP, who could?

We don’t expect Cisco to have principles. Nobody believed Microsoft, vicious bully of the 90s, was an Idealist. We expect those companies to have Jack Ma’s conception of a “business” etched into their souls. We expect them to please whichever Idealist threatens their profits.

But Google?

Ideals were part of Google’s founding manifesto. To be clear — conceding to a strong & unyielding Idealist is not “evil”! It’s just sensible. Smart. Rational. Pragmatic.

I’m not faulting Google for not going toe-to-toe with the CCP — but explore the “what if?” with me:

Alea Iacta Est: The War That Could Have Been

Nobody enjoys going to war. It’s bad for business.

But assume for a moment that Google had reacted to state-sponsored hacking in 2009 and state-directed laws demanding egregious censorship with defiant Idealism, how might things have played out?

Assuming Google had gone to war, there’s only one question that matters:

Could Google, circa 2010, have delivered its product to Chinese internet users through The Great Firewall?

In the hypothetical world where they tried, there are two major outcomes:

They succeed, servicing & ~monetizing the entire Chinese audience

The CCP blocks all foreign network traffic, adopting a forced isolationist policy ala North Korea or a narrow whitelist of acceptable foreign servers, severely hampering the ability of Chinese Tech firms to interact with the outside world

The wargame:

i) Talent & Funding

In Spring 2010 Google had LTM revenues of $26 Billion, more than $30 Billion in cash sitting around, ~20,000 employees, and a $3 Billion line of credit. As “warchests” go, it doesn’t get much better (at least not by 2010’s standards).

But Google also had something intangible in 2010: the highest concentration of PhDs, award-winning researchers, and credentialed academics of any major Tech company in the world.

Note the date source

It’s hard to imagine an organization anywhere in the world that had a higher bar for average computer science talent than Google.

During this same time period, the CCP had to turn to Cisco to deliver the technology to build its Great Firewall, as Huawei was not quite advanced enough yet.[1]

There were definitely talented individuals not working at Google. But as organizations go, Google reigned supreme.

ii) Execution

Alright, we’ve got the Talent, we’ve got the Funding, let’s pretend we’ve got the Motivation, how would Google have actually executed this plan?

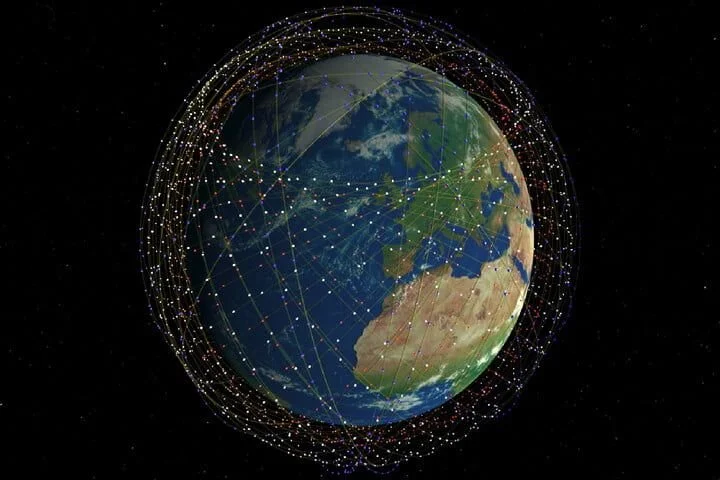

This is the internet:

When you type “www.google.com” into a browser, that request gets converted to a numerical address and is then Routed to the correct server, which replies with the website you asked for.

How does the CCP’s Great Firewall work?

They hired Cisco to lay the first bricks, which should tell you all you need to know: Cisco makes Routers.

If the website address you request is on a blacklist, the Router instead sends it to a dead end (and keeps a log of exactly which device requested such forbidden material):

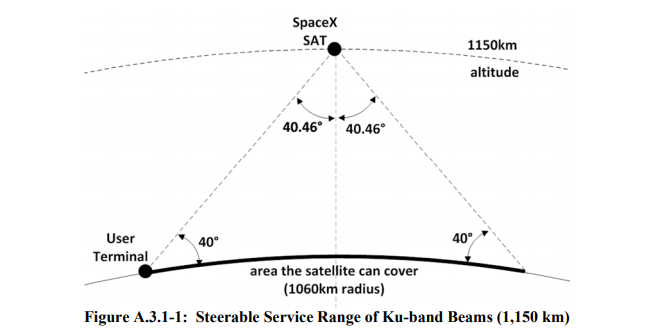

Every millennial visiting China knows that if you want to check up on Facebook or watch Netflix (yes, Netflix is banned too, and yes, it’s still Tech Protectionism), you’ll need to install and use a VPN:

See note [2] for a simple summary of how a VPN works

By keeping the VPN server outside The Great Firewall, a VPN makes your traffic look (relatively) benign to the Routers that would otherwise send you to a Dead End. As far as the CCP is concerned, you’re visiting a random address they’ve never heard of.[3]

Of course the second “PC” does not actually exist, it’s just a server source

I’m not smart enough or well educated enough to describe a full stack of technology that Google would have needed to succeed in 2010. Perhaps they would have had to build core parts of VPN technology into their own servers, maybe a novel and undetectable encryption method, potentially partnerships with other Tech companies or backdoors with Cisco…

Perhaps Google would have had to move domain names each day, or each hour, much like “Sci Hub” does today (I would link to it but…).

Maybe they escalate to launching satellites and blasting the internet down directly to billions of devices.

In the endgame, the CCP only wins if they block all unapproved content coming in and out — a whitelist instead of a blacklist — severely limited the potential value of the CCP’s domestic Technology companies.

Google’s goal is to make Zero-Sum plays win Zero-Sum prizes:

Either Google wins or the CCP loses.

Glaring Drawbacks

One obvious drawback of this plan is that Google’s Chinese users would have some measure of privacy, making them hard to advertise to via the targeted ads that we have all grown to love/hate.

Monetizing these users based on their cookies / user fingerprinting would be nearly impossible as Google would be creating a proxy VPN for each Chinese user. Instead they would need to be monetized based on their Search Requests (i.e. Google’s traditional model — certainly a viable one).

Another much bigger drawback lies in the fact that this would be a US-based corporate challenge on CCP legal sovereignty / authority. It’s unlikely this would be well received by the international community (understatement).

Still, it’s interesting to imagine the legal and ethical arguments that would come from such a confrontation. US Tech companies were seen (by traditional media outlets) as Heroes when they helped coordinate the Arab Spring. Baidu is on-record having no respect for US IP. Censorship rarely wins the popular vote, at least in the West. There’s enough factors in play that perhaps a good PR campaign could win out.

Flip-side: the origin of Western Imperialism in the Far East was an explicit desire to sell product into an untapped market, against the wishes and decrees of the ruling sovereign.[4]

Pictured: trying to sell product to Chinese citizens in the 1800s

Google doesn’t have its own warships (thank god), but the software wars might be just as dirty — remember the incident that sparked Google’s pull-out was a state-sponsored hack out of a Chinese University on Google’s server. And that’s when Google was playing by the rules.

Conflicts between Idealists escalate until someone taps out. Always. The winner gets to define the playing field for the following decades and the prize pool currently stands at $982 Billion:

Mary Meeker’s annual Tech Trends report — readers of my last essay might note the total absence of the world’s 4th largest economy on this list. The sum of circled market caps is ~$982B.

Play Zero-Sum Games, Win Zero-Sum Prizes

I’m not trying to start an international incident here — and neither was Google.

So none of this ever happened. It’s all just fun and games — this essay came out of a lively chat with friends over cocktails and burritos, nothing serious.

The Technological question — could Google have done it? — remains an open question. Remains the most fun question. It’s the core issue. At first it sounds impossible. I think they could’ve done it, but I can sometimes be too optimistic on these things.

But if I’m right, and if they could have made it work, then the decision not to escalate is an epoch-defining one.

It’s the reason Zuckerberg wasted his time with his full Q&A in Mandarin (in 2014). At the time, he seemed willing to engage in censorship if it meant market access. The MIT Technology Review ran this unflattering image alongside their story back in 2016:

But he’s now realized the doors are closed to him, regardless of his willingness to submit. So he’s changed his tune — see the full text of his Georgetown University speech 5 months ago:

This raises a larger question about the future of the global internet. China is building its own internet focused on very different values, and is now exporting their vision of the internet to other countries. Until recently, the internet in almost every country outside China has been defined by American platforms with strong free expression values. There’s no guarantee these values will win out. A decade ago, almost all of the major internet platforms were American. Today, six of the top ten are Chinese.

These are no longer the words of someone who wants to earn a seat at the CCP's table.

His frustration here is one of asymmetry — the CCP can export their vision, but Facebook (which he wants you to read as: “America”) is blocked from exporting a competing vision.

I want to end this by bringing back Mary Meeker’s annual internet trends report and comparing it to the same slides from 10 years ago (i.e. 2010) and 16 years ago (i.e. 2004):

Click to embiggen. Left: 2020 Tech Leaders, Chinese firms circled. Right: 2010 Tech Leaders & 2004 Tech Leaders source

The list has expanded from “Top 15” to “Top 30” to reflect the growth of the Tech industry as a whole.[5]

In terms of “Market Cap Leaders”, China has gone from 1 spot in 2004, to 3 spots in 2010, to 7 spots in 2020. It’s genuinely impressive stuff.

Stop looking at China for a moment and consider the stunning lack of other nations on this list. With the sole exception of China, not a single non-US nation has more than 1 spot in today’s top 30.

Even if we treat the “European Union” as a single block, Spotify is their only offering that earns a spot on Mary Meeker’s slide.

On the surface, this is very odd. Most other global industries have major representatives from the EU & Japan in the top 30, from finance to automotive.

To veterans of the Tech industry, this is not so surprising. Software is eating the world. Software is infinitely scalable. Software has near-zero marginal cost. Software can be delivered instantaneously. Anytime, anywhere, and to anyone.

If ever there was an industry whose natural inclinations tended towards monopoly centralized suppliers, Technology is it. As Zuckerberg says, we’re happy enough when that centralized location is on American shores and (loosely) follows Western liberal values — but many have not considered that as with winning in the US market, victory in the massive Chinese market provides enough firepower/free-cash-flow to pursue other markets.

Many see Zuckerberg as perhaps the worst messenger you could imagine to deliver this message. The cutthroat skills it takes to build a global monopoly in any business are rarely the ones we praise in our Liberal Arts Educations. And yet that’s exactly my point.

Harvard, "Veritas”, produces Zuckerberg, and the Western media recoils in horror. Do we imagine Peking University will produce Christ-like monopolists?

Of course not. Any merciful aspiring monopolists will be metaphorically-Trotsky’d within a quarter, no matter their Alma Mater.

My last essay was focused on Germany’s success with Industrial exports, and I ended it with a call to:

Consider the lessons of this case study carefully — who has won, who has lost, and how they ended up where they did — and choose your own adventure.

China’s stunning success in Technology over the last two decades — and the total failure of other nations to build an enduring Tech industry — suggests its own lessons. Those lessons are not as optimistic as the ones that can be drawn from Germany’s Industrial successes.

They are not as palatable.

They are Zero-Sum lessons.

I’ve spent this whole essay analyzing Google vs. the CCP, but in many ways that’s not what the essay is about. It’s about all the other great economies whose names do not appear on a list of Global Internet Market Cap Leaders. It’s easy to think of a hundred “just-so” reasons why each other nation has failed to build a globally-competitive domestic Tech industry…

But it’s easier — and more intellectually honest — to dive in on the one counter example. It is the fight, the Idealistic commitment to political ownership, that sets China apart.

As a good American citizen and a member of America’s Tech community, I ought to ask others to ignore the lessons of this case study — who has won, who has lost, and how the winners achieved their victories.

As a student of the game, I can’t help but admire the CCP’s foresight, commitment, and successful execution. Say one thing for the CCP, say they can bend a whole nation to a single task and hold it there for two decades.

The fundamentals of Technology tend towards centralized global suppliers, which looks very attractive to central planners. If you’re running — or working for — a Technology Business, you should know that there’s a lot of upside for someone who can block your market access.

Now I’m not saying you should fight them for that market access.

I’m just saying you could.

Notes

[0] The answer to this question grew too long, so it’ll have to be its own post sometime later.

[1] One imagines this made Cisco popular with the NSA:

[2] A VPN works by establishing a “Virtual” “Private” connection between your PC and an innocent-looking second PC far away from you. All your requests for webpages are sent to that second PC, fully encrypted (hence: “Private”). That second PC then forwards your request to a router on your behalf, receives the webpage/content you asked for, and then encrypts that content and sends it back to you.

[3] The CCP has been playing a game of cat and mouse with VPN providers for the last few years, with fun highlights like the Firewall’s chief architect using a VPN during a presentation when he was unable to visit a website for his talk.

[4] Hot take here: given how progressive Google appears to be, you could maybe make an argument that modern progressive ideology successfully averted the resurgence of Western Imperialism and “The Technology Wars”.

I recommend a few drinks before you make that argument.

[5] In 2004, the 10th largest internet company (WebMD) had a market cap of $2B. By 2010, the 10th largest (Salesforce) had a market cap of $15B (+650% over 6 years).

By 2020, the 10th largest internet company (Paypal) has a market cap of $134B (+790% over 10 years).

That’s a LOT of growth.

- The King is Dead, Long Live the King

- A Picture Tells A Thousand Words: A Tale of Two Stocks

- Screw A Picture, Here's A Thousand Words

- Idealists Draw The Playing Field, Pragmatists Play The Game

- Alea Iacta Est: The War That Could Have Been

- Potential Drawbacks

- Play Zero-Sum Games, Win Zero-Sum Prizes

- Notes

![See note [2] for a simple summary of how a VPN works](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a571a7d80bd5e91de77e8e6/1584298437316-7FB8LLHG80TJYZBNCOJE/vpn_for_china.png)